(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, May 19, 2021 - Specialized immune cells that accumulate in the brain in the days and weeks after a stroke promote neural functions in mice, pointing to a potential immunotherapy that may boost recovery after the acute injury is over, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine neurologists found.

The study, published today in the journal Immunity, demonstrated that a population of specialized immune cells, called regulatory T (Treg) cells, serve as tissue repair engineers to promote functional recovery after stroke. Boosting Treg cells using an antibody complex treatment, originally designed as a therapy after transplantation and for diabetes, improved behavioral and cognitive functions for weeks after a stroke in mice compared to those that did not receive the antibody complex.

"The beauty of this treatment is in its wide therapeutic window," said senior author Xiaoming Hu, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Neurology at Pitt's School of Medicine. "With most strokes, you have four and a half hours or less when you can give medication called tPA to reopen a blocked blood vessel and expect to rescue neurons. We're excited to identify a mechanism that may promote brain recovery by targeting non-neuronal cells well after this window closes."

Previous research in stroke has been focused on developing new drugs to reduce neuronal death. And whereas these acute stroke treatments quickly lose effectiveness after neurons die, Treg cells remain active for weeks after the injury.

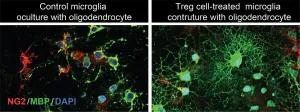

True to their name, Treg cells are immune cells that regulate the immune response, including curtailing excessive inflammation that could harm more than help. Hu and her colleagues observed that the levels of Treg cells infiltrating the brain began to increase about a week after a stroke and continued increasing up to five weeks later. So, they did multiple tests in mice after they'd had strokes, paying particular attention to the brain's white matter--which is the brain tissue through which neurons pass messages, turning thoughts into actions, like lifting food to your mouth or saying the name of an object you're looking at.

Mice that were genetically unable to produce Treg cells fared worse than mice with a robust Treg cell response. Interestingly, it was only in the latter phases of stroke recovery that the Treg cell-depleted mice suffered impairments in white matter integrity and behavioral performance compared to mice with a normal Treg cell response.

Additionally, when normal mice were given an antibody complex called "IL-2:IL-2Ab" to boost their Treg cell levels after a stroke, their white matter integrity improved even more and neurological functions were rescued over the long term. The mice with more Treg cells had an easier time moving and had better memories, allowing them to navigate mazes faster after a stroke than their non-treated counterparts.

"This strongly suggests that, rather than working to preserve white matter structure and function immediately after a stroke, Treg cells influence long-term white matter repair and regeneration," said Hu, also a member of the Pittsburgh Institute of Brain Disorders and Recovery and a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) investigator. "Our findings pave the way for a therapeutic approach to stroke and other neurological disorders that involve excessive brain inflammation and damage to the white matter. Treg cells appear to hold neurorestorative potential for stroke recovery."

Hu stressed that there are still many hurdles to cross before Treg cells could be used in humans for stroke recovery. Namely, research is needed to determine the best way to boost the number of Treg cells in stroke victims. This could be done by improving IL-2:IL-2Ab so that it better stimulates production of Treg cells with fewer side effects, or a personalized therapy could be developed where some cells are taken from an established Treg cell bank and used to grow custom Treg cells in the lab, which could then be infused back into the patient.

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on this research are Ligen Shi, M.D., Ph.D., Zeyu Sun, M.D., Wei Su, M.D., Di Xie, M.D., Qingxiu Zhang, M.D., Xuejiao Dai, M.D., Ph.D., Kartik Iyer, B.S., T. Kevin Hitchens, Ph.D., Lesley M. Foley, B.S., Sicheng Li, Ph.D., Donna B. Stolz, Ph.D., Kong Chen, Ph.D., Ying Ding, Ph.D., and Angus W. Thomson, Ph.D., all of Pitt; Fei Xu, B.S., and Jun Chen, M.D., both of Pitt and the VA Pittsburgh Health Care System, and Rehana K. Leak, Ph.D., of Pitt and Duquesne University.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant NS094573 and VA grant I01 BX003651.

To read this release online or share it, visit https://www.upmc.com/media/news/051921-hu-treg-stroke.

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation's leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region's economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.medschool.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

INFORMATION:

Contact: Allison Hydzik

Office: 412-647-9975

Mobile: 412-559-2431

E-mail: HydzikAM@upmc.edu

Contact: Anastasia Gorelova

Mobile: 412-491-9411

E-mail: GorelovaA@upmc.edu

The yeast Candida albicans can cause itchy, painful urinary tract and vaginal yeast infections. For women in low-resource settings who lack access to healthcare facilities, these infections create substantial social and economic burdens. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Omega have developed color-changing threads that turn bright pink in the presence of C. albicans. When embedded in tampons or sanitary napkins, they could allow women to quickly and discreetly self-diagnose vulvovaginal yeast infections, the researchers say.

According to the Mayo Clinic, about 75% of women will experience a yeast infection, or vulvovaginal candidiasis, at least ...

Researchers have found the elusive genetic element controlling the elongated grains and glumes of a wheat variety identified by the renowned botanist Carl Linnaeus more than 250 years ago.

The findings relating to Polish wheat, Triticum polonicum, could translate into genetic improvements and productivity in the field.

Wheat, in bread, pasta, and other forms, is a vital energy and protein source for humans. Each individual grain is nestled within the glumes and other leaf-like organs called lemma and palea which affect the grain's final size, shape, and weight.

Characterised by Linnaeus in 1762, Polish wheat has long grains, glumes, ...

The sun delivers more energy to Earth in one hour than humanity consumes over an entire year. Scientists worldwide are searching for materials that can cost-effectively and efficiently capture this carbon-free energy and convert it into electricity.

Perovskites, a class of materials with a unique crystal structure, could overtake current technology for solar energy harvesting. They are cheaper than materials used in current solar cells, and they have demonstrated remarkable photovoltaic properties -- behavior that allows them to very efficiently convert sunlight into electricity.

Revealing the nature of perovskites at the atomic scale is critical to understanding their promising capabilities. ...

Scientists, governments and corporations worldwide are racing against the clock to fight climate change, and part of the solution might be in our soil. By adding carbon from the atmosphere to depleted soil, farmers can both increase their yields and reduce emissions. A cover story in Chemical & Engineering News, the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society, explores what it would take to get this new practice off the ground.

Historically, agricultural soil has provided crops with the nutrients needed to grow, write Senior Editors Melody Bomgardner and Britt Erickson. Today, most soil is considered degraded, leading farmers to rely on fertilizer, irrigation and pesticides, all of which are costly. Scientific advancements ...

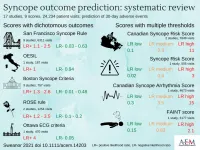

Des Plaines, IL - The Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS) is an accurate validated prediction score for emergency department patients with unexplained syncope. These are the results of a study titled Multivariable risk scores for predicting short-term outcomes for emergency department patients with unexplained syncope: A systematic review, to be published in the May issue of Academic Emergency Medicine (AEM) journal, peer-reviewed journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM).

Syncope is a common presentation to an emergency department, with patients at risk of experiencing an adverse event within 30 days. Without a standardized risk stratification system of patients, there will be health care ...

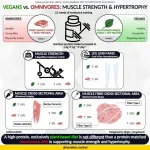

Protein intake is more important than protein source if the goal is to gain muscle strength and mass. This is the key finding of a study that compared the effects of strength training in volunteers with a vegan or omnivorous diet, both with protein content considered adequate.

In the study, which was conducted by researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil, 38 healthy young adults, half of whom were vegans and half omnivores, were monitored for 12 weeks. In addition to performing exercises to increase muscle strength and mass, the volunteers followed either a mixed diet with both ...

Artificial intelligence is providing new opportunities in a range of fields, from business to industrial design to entertainment. But how about civil engineering and city planning? How might machine- and deep-learning help us create safer, more sustainable, and resilient built environments?

A team of researchers from the NSF NHERI SimCenter, a computational modeling and simulation center for the natural hazards engineering community based at the University of California, Berkeley, have developed a suite of tools called BRAILS -- Building Recognition ...

Quality of life relating to physical and mental health can be a key element in the treatment of obese adults. For this reason, interdisciplinary clinical measures including cognitive and behavioral therapy may produce more significant outcomes for these people, reducing not just weight but also symptoms of depression.

This is the main conclusion of a study conducted in Brazil by the Obesity Research Group at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) in Santos, São Paulo state, and published in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition.

Considered one of the world’s major public health problems, obesity has ...

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Self-affirmation, the practice of reflecting upon one's most important values, can aid Black medical students in reaching their residency goals. But conversely, it can lead to the perception that they are less qualified for a prestigious residency than their peers.

The pandemic has underscored the racial disparities in the quality of healthcare, a field in which Black Americans are vastly underrepresented as medical physicians.

New Northwestern University research aims to address the "leaky pipeline" preventing Black medical students from completing medical school to pursuing residencies in high-need and underrepresented areas.

Sylvia Perry, assistant professor of psychology in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern, is the ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Though obesity in midlife is linked to an increased risk for Alzheimer's disease, new research suggests that a high body mass index later in life doesn't necessarily translate to greater chances of developing the brain disease.

In the study, researchers compared data from two groups of people who had been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment - half whose disease progressed to Alzheimer's in 24 months and half whose condition did not worsen.

The researchers zeroed in on two risk factors: body mass index (BMI) and a cluster of ...