(Press-News.org) Melting glaciers and polar ice sheets are among the dominant sources of sea-level rise, yet until now, the water beneath them has remained hidden from airborne ice-penetrating radar.

With the detection of groundwater beneath Hiawatha Glacier in Greenland, researchers have opened the possibility that water can be identified under other glaciers from the air at a continental scale and help improve sea-level rise projections. The presence of water beneath ice sheets is a critical component currently missing from glacial melt scenarios that may greatly impact how quickly seas rise - for example, by enabling big chunks of ice to calve from glaciers vs. stay intact and slowly melt. The findings, published in Geophysical Research Letters May 20, could drastically increase the magnitude and quality of information on groundwater flowing through the Earth's poles, which had historically been limited to ground-based surveys over small distances.

"If we could potentially map water underneath the ice of other glaciers using radar from the air, that's a game-changer," said senior study author Dustin Schroeder, an assistant professor of geophysics at Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth).

The data was collected in 2016 as part of NASA's Operation IceBridge using a wide-bandwidth radar system, a newer technique that has only started being used in surveys in the last few years. Increasing the range of radio frequencies used for detection allowed the study authors to separate two radar echoes - from the bottom of the ice sheet and the water table - that would have been blurred together by other systems. While the team suspected groundwater existed beneath the glacier, it was still surprising to see their hunch confirmed in the analyses.

"When you see these anomalies, most of the time they don't pan out," said lead study author Jonathan Bessette, a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who conducted the research as a SUNY Buffalo undergraduate through the Stanford Summer Undergraduate Research in Geoscience and Engineering Program (SURGE).

Based on the radar signal, the study team constructed two possible models to describe Hiawatha Glacier's geology: Frozen land with thawed ice below it or porous rock that enables drainage, like when water flows to the bottom of a vase filled with marbles. These hypotheses have different implications for how Hiawatha Glacier may respond to a warming climate.

Groundwater systems may play a more significant role than what researchers currently model in ice sheets for sea-level-rise projections, according to Schroeder. The researchers hope their findings will prompt further investigation of the possibility for additional groundwater detection using airborne radar, which could potentially be deployed on a grand scale to collect hundreds of miles of data per day.

"What society wants from us are predictions of sea level - not only now, but in futures with different greenhouse gas emission scenarios and different warming scenarios - and it is not practical to survey an entire continent with small ground crews," Schroeder said. "Groundwater is an important player, and we need to survey at the continental scale so that we can make continental-scale projections."

INFORMATION:

Schroeder is also an assistant professor, by courtesy, of electrical engineering and a center fellow, by courtesy, at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. Study co-authors include Thomas Jordan, who conducted research as a Stanford postdoctoral researcher on a Marie Curie fellowship from the University of Bristol, and Joseph MacGregor of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

The research was supported by an NSF CAREER award and NASA.

New research led by the University of Kent's School of Psychology has found that some brain activity methods used to detect incriminating memories do not work accurately in older adults.

Findings show that concealed information tests relying on electrical activity of the brain (electroencephalography [EEG]) are ineffective in older adults because of changes to recognition-related brain activity that occurs with aging.

EEG-based forensic memory detection is based on the logic that guilty suspects will hold incriminating knowledge about crimes they have committed, and therefore their brains will elicit a recognition response ...

For the first time, researchers have successfully sequenced the entire genome from the skull of Peştera Muierii 1, a woman who lived in today's Romania 35,000 years ago. Her high genetic diversity shows that the out of Africa migration was not the great bottleneck in human development but rather this occurred during and after the most recent Ice Age. This is the finding of a new study led by Mattias Jakobsson at Uppsala University and being published in Current Biology.

"She is a bit more like modern-day Europeans than the individuals in Europe 5,000 years earlier, but the difference is much less than we had thought. We can see that she is not a direct ancestor of modern Europeans, but she is a predecessor of the hunter-gathers that lived in Europe until the end of the last ...

DURHAM, N.C. - A newly identified group of antibodies that binds to a coating of sugars on the outer shell of HIV is effective in neutralizing the virus and points to a novel vaccine approach that could also potentially be used against SARS-CoV-2 and fungal pathogens, researchers at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute report.

In a study appearing online May 20 in the journal Cell, the researchers describe an immune cell found in both monkeys and humans that produces a unique type of anti-glycan antibody. This newly described antibody has the ability to attach ...

Juvenile salmon migrating to the sea in the Sacramento River face a gauntlet of hazards in an environment drastically modified by humans, especially with respect to historical patterns of stream flow. Many studies have shown that survival rates of juvenile salmon improve as the amount of water flowing downstream increases, but "more is better" is not a useful guideline for agencies managing competing demands for the available water.

Now fisheries scientists have identified key thresholds in the relationship between stream flow and salmon survival that can serve as actionable targets for managing water resources in the Sacramento River. The new analysis, published May 19 in Ecosphere, revealed nonlinear ...

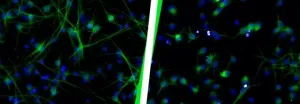

Today, proteins that can be controlled with light are a widely used tool in research to specifically switch certain functions on and off in living organisms. Channelrhodopsins are often used for the technique known as optogenetics: When exposed to light, these proteins open a pore in the cell membrane through which ions can flow in; this is how nerve cells can be activated. A team from the Centre for Protein Diagnostics (PRODI) at Ruhr-Universität Bochum has now used spectroscopy to discover a universal functional mechanism of channelrhodopsins that determines their efficiency as a channel and thus as an optogenetic tool. The researchers led by Professor Klaus ...

Microfluidic technologies have seen great advances over the past few decades in addressing applications such as biochemical analysis, pharmaceutical development, and point-of-care diagnostics. Miniaturization of biochemical operations performed on lab-on-a-chip microfluidic platforms benefit from reduced sample, reagent, and waste volumes, as well as increased parallelization and automation. This allows for more cost-effective operations along with higher throughput and sensitivity for faster and more efficient sample analysis and detection.

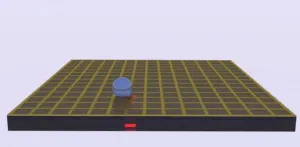

Optoelectrowetting (OEW) is a digital optofluidic technology that is based on the principles of light-controlled electrowetting and enables ...

Since our ancestors infected themselves with retroviruses millions of years ago, we have carried elements of these viruses in our genes - known as human endogenous retroviruses, or HERVs for short. These viral elements have lost their ability to replicate and infect during evolution, but are an integral part of our genetic makeup. In fact, humans possess five times more HERVs in non-coding parts than coding genes. So far, strong focus has been devoted to the correlation of HERVs and the onset or progression of diseases. This is why HERV expression has been studied in samples of pathological origin. Although important, these studies ...

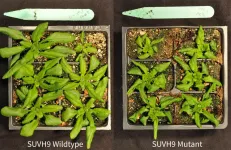

Passing down a healthy genome is a critical part of creating viable offspring. But what happens when you have harmful modifications in your genome that you don't want to pass down? Baby plants have evolved a method to wipe the slate clean and reinstall only the modifications that they need to grow and develop. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor & HHMI Investigator Rob Martienssen and his collaborators, Jean-Sébastien Parent and Institut de Recherche pour le Développement Université de Montpellier scientist Daniel Grimanelli, discovered one of the genes responsible for reinstalling modifications in a baby plant's genome.

A plant's genomic modifications--called epigenetic ...

The study sought to describe and explain gender pay differences in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services between 2010 and 2018. HHS comprises a quarter of the country's governmental public health workers, with over 80,000 employees.

Understanding what may be driving wage gaps at HHS provides opportunities for employers and legislators to take action to support women in the health care field, said lead author Zhuo "Adam" Chen, an associate professor of health policy and management at UGA's College of Public Health.

"A large percentage of the health care workforce are women," said Chen. "If you have underpaid women in the profession, I don't think it spells good things for the public health system."

Chen ...

Maywood, Ill. - May 19, 2021 - A team of scientists from Loyola University Chicago's Stritch School of Medicine have discovered a critical component for renewing the heart's molecular motor, which breaks down in heart failure.

Approximately 6.2 million Americans have heart failure, an often fatal condition characterized by the heart's inability to pump enough blood and oxygen throughout the body. This discovery could represent a novel approach to repair the heart.

Their findings, published in the May 19 issue of Nature Communications, show how a protein called BAG3 helps replace "worn-out" components of the cardiac sarcomere. The sarcomere is a microscopic ...