(Press-News.org) A particular type of dendritic cell is responsible for the tissue damage that occurs in non-alcoholic steatohepatits (NASH) in mice and humans. The dendritic cells cause aggressive, proinflammatory behavior in T cells, as now discovered by researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in collaboration with colleagues from Israeli research institutes. Blocking these dendritic cells alleviates symptoms in mice. This type of approach might also prevent the development of serious liver damage in NASH patients.

Obesity is extremely widespread in the Western world, and 90 percent of those affected show signs of fatty degeneration of the liver. If they maintain an unhealthy lifestyle over a long period (high-calorie diet, sedentary lifestyle), liver cell death occurs in around a fifth of these people, resulting in inflammation of the liver, referred to as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH can lead to liver fibrosis, life-threatening liver cirrhosis and liver cancer.

In addition to its well-known role in metabolism and in filtering toxins, the liver also has a strategic function as part of the immune system, acting as the primary line of defense against all microbial toxins and food contaminants that enter the body from the intestines via the portal vein. In order to perform this task, a whole army of different immune cells patrol the liver.

"We wanted to find out which immune or inflammatory cells in the liver promote NASH and the liver damage associated with it," explained Mathias Heikenwälder from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). DKFZ researchers have now addressed the topic in collaboration with colleagues from the Weizmann Institute of Sciences and Sheba Medical Center in Israel. To do so, they analyzed the connection between the composition of the immune cell population in the liver and the degree of NASH-related liver damage. This enabled them to identify a particular type of immune cell that promotes progression of the disease - in both mice and humans.

Clue from laboratory mice on "junk food"

In order to investigate the immune system in NASH, the researchers fed laboratory mice a diet lacking essential nutrients but enriched with lipids and cholesterol - comparable to our "junk food" - and observed the development of NASH. They studied the liver immune cells using single-cell RNA sequencing and discovered an unusually high number of a particular kind of cell, known as type 1 dendritic cells (cDC1), in the liver of NASH mice.

This phenomenon was not limited to mice. In tissue samples taken from patients in liver biopsies, the researchers found a correlation between the number of cDC1 cells and the extent of liver damage typical of NASH.

Do the cDC1 cells actually have an effect on liver pathology? The researchers pursued two channels of investigation here. They studied genetically modified mice lacking cDC1. In addition, they blocked cDC1 in the liver using specific antibodies. In both approaches, lower cDC1 activity was associated with a decrease in liver damage.

Dendritic cells normally only survive for a few days and need to be continually replaced by the immune system. The researchers discovered that the NASH-related tissue damage modulates the hematopoietic system in the bone marrow, as a result of which the cDC1 precursors divide more often and replenish the supply more readily.

Dendritic cells induce aggressive behavior in T cells

In a normal immune response, dendritic cells screen the organs for conspicuous immunologic features and then continue on to the neighboring lymph nodes - the command centers of the immune response - to pass on this information to the T cells. In NASH subjects, the German-Israeli team has now discovered that the cDC1 induce inflammatory and more aggressive behavior in T cells in the lymph nodes responsible for the liver, causing liver damage and leading to progression of the disease. "It is only recently that we identified these autoaggressive T cells as being responsible for liver damage in NASH. Now we also understand what induces this harmful behavior," Mathias Heikenwälder remarked.

Now that the cDC1 have been shown to play a key role in the progression of NASH, targeted manipulation of these cells might offer a new way of treating inflammation of the liver and its serious repercussions. "We are increasingly recognizing that certain cells of the immune system are involved in the development of different diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer's disease. Medicine is thus increasingly using ways of modulating the immune system and using drugs to push it in the right direction. This kind of approach might also work to prevent serious liver damage in NASH patients," Heikenwälder explained.

Eran Elinav, also a senior author of the study and head of research groups at DKFZ and the Weizmann Institute, believes that it is highly probable that gut bacteria affect the immune cells in this disease: "We now aim to find out how the gut and its bacteria influence activation of the immune cells in the liver. By doing so, we hope to be able to develop new treatment strategies."

INFORMATION:

Aleksandra Deczkowska, Eyal David, Pierluigi Ramadori, Dominik Pfister, Michal Safran, Baoguo Li, Amir Giladi, Diego Adhemar Jaitin, Oren Barboy, Merav Cohen, Ido Yofe, Chamutal Gur, Shir Shlomi-Loubato, Sandrine Henri, Yousuf Suhail, Mengjie Qiu, Shing Kam, Hila Hermon, Eylon Lahat, Gil Ben-Yakov, Oranit Cohen-Ezra, Yana Davidov, Mariya Likhter, David Goitein, Susanne Roth, Achim Weber, Bernard Malissen, Assaf Weiner, Ziv Ben-Ari, Mathias Heikenwälder*, Eran Elinav*, Ido Amit*: XCR1+ type 1 conventional dendritic cells drive liver pathology in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

Nature Medicine 2021, DOI: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-021-01344-3

A picture is available for download:

https://www.dkfz.de/de/presse/pressemitteilungen/2021/bilder/NASH-cDCs-40X.jpg

Caption: Immunofluorescence analysis of a NASH-affected human liver. DC1 cells (stained red, CD 141) patrol through the liver sinusoids (yellow, CD31). Black holes indicate lipid droplets.

Source: Heikenwälder / DKFZ

The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) with its more than 3,000 employees is the largest biomedical research institution in Germany. More than 1,300 scientists at the DKFZ investigate how cancer develops, identify cancer risk factors and search for new strategies to prevent people from developing cancer. They are developing new methods to diagnose tumors more precisely and treat cancer patients more successfully. The DKFZ's Cancer Information Service (KID) provides patients, interested citizens and experts with individual answers to all questions on cancer.

Jointly with partners from the university hospitals, the DKFZ operates the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) in Heidelberg and Dresden, and the Hopp Children's Tumour Center KiTZ in Heidelberg. In the German Consortium for Translational Cancer Research (DKTK), one of the six German Centers for Health Research, the DKFZ maintains translational centers at seven university partner locations. NCT and DKTK sites combine excellent university medicine with the high-profile research of the DKFZ. They contribute to the endeavor of transferring promising approaches from cancer research to the clinic and thus improving the chances of cancer patients.

The DKFZ is 90 percent financed by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and 10 percent by the state of Baden-Württemberg. The DKFZ is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers.

Solar geoengineering -- putting aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight and reduce global warming -- is not a fix-all for climate change but it could be one of several tools to manage climate risks. A growing body of research has explored the ability of solar geoengineering to reduce physical climate changes. But much less is known about how solar geoengineering could affect the ecosystem and, particularly, agriculture.

Now, research from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) finds that solar geoengineering may be surprisingly effective in alleviating some of the worst impacts of ...

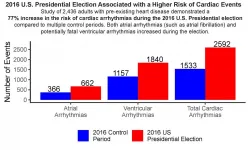

CHAPEL HILL, NC - American politics can be stressful and confrontational, which can lead to anger. The combination of intense stress and negative emotions can trigger potentially fatal cardiovascular events in people who are susceptible to these health issues. But the direct link between a stressful political election and an increase in cardiac events hadn't been established, until now. A new study in the Journal of the American Heart Association is the first to show that exposure to a stressful political election is strongly associated with an increase in potentially life-threatening cardiac events.

"This retrospective ...

A team led by a social work researcher at The University of Toledo has published the first empirical evidence that emotional support animals can provide quantifiable benefits to individuals with serious mental illness who are experiencing depression, anxiety and loneliness.

The research brings credence to the many anecdotal reports of emotional support animals having positive impacts on chronic mental health issues.

"This is the first peer-reviewed, published scientific evidence that emotional support animals may benefit people's mental health," said Dr. Janet Hoy-Gerlach, a professor of social work and the lead investigator on the project. "My hope is that our pilot study catalyzes additional research in this area with more rigorous ...

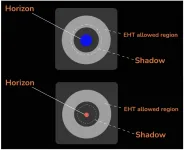

FRANKFURT. As first pointed out by the German astronomer Karl Schwarzschild, black holes bend space-time to an extreme degree due to their extraordinary concentration of mass, and heat up the matter in their vicinity so that it begins to glow. New Zealand physicist Roy Kerr showed rotation can change the black hole's size and the geometry of its surroundings. The "edge" of a black hole is known as the event horizon, the boundary around the concentration of mass beyond which light and matter cannot escape and which makes the black hole "black". Black holes, theory predicts, can be described by a handful ...

When scientists hunt for life, they often look for biosignatures, chemicals or phenomena that indicate the existence of present or past life. Yet it isn't necessarily the case that the signs of life on Earth are signs of life in other planetary environments. How do we find life in systems that do not resemble ours?

In groundbreaking new work, a team* led by Santa Fe Institute Professor Chris Kempes has developed a new ecological biosignature that could help scientists detect life in vastly different environments. Their work appears as part of a special issue of theBulletin ...

The chemical bisphenol F (found in plastics) can induce changes in a gene that is vital for neurological development. This discovery was made by researchers at the universities of Uppsala and Karlstad, Sweden. The mechanism could explain why exposure to this chemical during the fetal stage may be connected with a lower IQ at seven years of age - an association previously seen by the same research group. The study is published in the scientific journal Environment International.

"We've previously shown that bisphenol F (BPF for short) may be connected with children's cognitive development. However, with this study, we can now begin to understand which biological mechanisms may explain such a link, which is unique for an epidemiological study." ...

A new study provides public health planning authorities with a method of calculating the number of COVID-19 isolation beds they would need for people experiencing homelessness based on level of infection in the city. The research holds promise for controlling spread of the virus - or future infectious diseases - in a population that is highly vulnerable and less likely than many others to access health care services.

The report, developed to support public health decision-making in Austin, Texas, was recently published by PLOS ONE. The paper's first author is an undergraduate student at The University of Texas at Austin, Tanvi Ingle, who harnessed ...

In April 2017, a landslide in Mocoa, Colombia, ripped through a local town, killing more than 300 people. Nicolás Pérez-Consuegra grew up about 570 miles north in Santander, Colombia, and was shocked as he watched the devastation on television. At that time, he was an undergraduate intern at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. As a budding geologist raised hiking the tropical mountains of Colombia, he wondered, what causes greater erosion in some areas of the mountains than in others? And, is it tectonic forces - where Earth's tectonic plates slide against one another leading to the formation of steep mountains - or high precipitation rates, that play a more important role in causing erosion within that region?

To answer those questions would require a geological ...

Scientists have discovered that the way in which neurons are connected within regions of the brain, can be a better indicator of disease progression and treatment outcomes for people with brain disorders such as epilepsy.

Many brain diseases lead to cell death and the removal of connections within the brain. In a new study, published in Human Brain Mapping, a group of scientists, led by Dr Marcus Kaiser from the School of Medicine at the University of Nottingham, looked at epilepsy patients undergoing surgery.

They found that changes in the local network within brain regions can be a better predictor ...

More than 90 years ago, astronomer Edwin Hubble observed the first hint of the rate at which the universe expands, called the Hubble constant.

Almost immediately, astronomers began arguing about the actual value of this constant, and over time, realized that there was a discrepancy in this number between early universe observations and late universe observations.

Early in the universe's existence, light moved through plasma--there were no stars yet--and from oscillations similar to sound waves created by this, scientists deduced that the Hubble constant was about 67. This means the universe expands about 67 kilometers per second faster every 3.26 million light-years.

But this observation differs when scientists look at the universe's ...