The driving force behind tropical mudslides

A Syracuse University Ph.D. candidate leads a research expedition in search of answers to erosion in his home country of Colombia

2021-05-20

(Press-News.org) In April 2017, a landslide in Mocoa, Colombia, ripped through a local town, killing more than 300 people. Nicolás Pérez-Consuegra grew up about 570 miles north in Santander, Colombia, and was shocked as he watched the devastation on television. At that time, he was an undergraduate intern at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. As a budding geologist raised hiking the tropical mountains of Colombia, he wondered, what causes greater erosion in some areas of the mountains than in others? And, is it tectonic forces - where Earth's tectonic plates slide against one another leading to the formation of steep mountains - or high precipitation rates, that play a more important role in causing erosion within that region?

To answer those questions would require a geological understanding of the evolution of the mountains in Colombia. During his undergraduate internship, Pérez-Consuegra studied the mountains near the towns of Sibundoy and Mocoa in the southern region of Colombia. There, he observed thick rainforests covering steep mountains and many landslide scars in the cliffs. There were also many landslides on the road leading him to believe that the tension and release of pressure along tectonic faults was shaking the landscape and removing rocks from its surface and shedding it into the rivers.

To find out more about the forces at play that were shaping the steep terrain of that region, Pérez-Consuegra pursued a doctoral degree in the College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences (EES). He says the opportunity to develop his own research ideas was one of the key reasons he chose Syracuse University. Pérez-Consuegra led the study from start to finish, proposing the research questions, hypotheses and methodology, with help from his Ph.D. advisor Gregory Hoke, associate professor and associate chair of EES, and Paul Fitzgerald, professor and director of graduate studies in EES. He also obtained research grants and support from EES and a number of outside sources including a National Geographic Early Career Grant and more, which fully funded three field expeditions to Colombia and the analytical work on rock samples collected there.

Pérez-Consuegra and Hoke conducted field research in the Eastern Cordillera portion of the Colombian Andes. During those expeditions the team hiked and traveled by both car and boat to various altitudes to collect over 50 rock samples. Rocks were then shipped to Syracuse University and processed in labs to extract the thermochronology data.

According to Pérez-Consuegra, a thermochronometer is like a stopwatch that starts ticking once a rock cools through a specific range of temperatures, keeping track of the time it takes for the subsequent journey to the Earth's surface. The mineral apatite is the radioactive stopwatch that he employs in his studies. Several kilograms of rock sample are processed to yield a few grams of apatite which contain two types of temperature-dependent stopwatches, or thermochronometers. Researchers can figure out the long-term erosion rate by figuring out how fast a rock moves toward the Earth's surface, using a formula that converts temperature to depth below the Earth's surface and then dividing depth by time.

Pérez-Consuegra's study revealed that the highest erosion rates occur near the places that have the most tectonically active faults. While precipitation may act as a catalyst for erosion on the surface of the mountains, the main force at play are faults where rock is exhuming from deep below the Earth's surface at faster rates.

"Tectonically active faults are causing uplift of the mountains surrounding Mocoa and are also making the landscape steeper," Pérez-Consuegra says. "Steeper and taller mountains are more prone to have landslides. Rainfall, and specifically torrential rains, can trigger the landslides, but what sets the stage are the tectonic processes."

Hoke says that while geomorphologists would like to think that rainfall rates can take over as the major influence on mountain formation, Pérez-Consuegra's research proves that Earth's internal deformation is the main factor.

"While prior work within a bullseye of high-rainfall in Colombia's Eastern Cordillera initially pointed towards a strong climate control on mountain growth, Nicolás' work expanded the same types of observations to another precipitation hotspot over 250 miles away and found the rates at which rock is transported to the surface were dependent on fault activity, and not precipitation amount," Hoke says.

Pérez-Consuegra, who will start a postdoctoral fellowship in environmental sciences at MIT in the fall, notes that geological knowledge is essential for predicting what areas in a tropical mountain range are more prone to have landslides, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, and the catastrophic consequences that these events might have in the surrounding populations.

"It is important to invest in doing better geological mapping in tropical mountains, to better understand the spatial distribution and geometries of tectonically active faults," Pérez-Consuegra says.

Read more about Pérez-Consuegra's research in the journal Tectonics: "The Case for Tectonic Control on Erosional Exhumation on the Tropical Northern Andes Based on Thermochronology Data."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-20

Scientists have discovered that the way in which neurons are connected within regions of the brain, can be a better indicator of disease progression and treatment outcomes for people with brain disorders such as epilepsy.

Many brain diseases lead to cell death and the removal of connections within the brain. In a new study, published in Human Brain Mapping, a group of scientists, led by Dr Marcus Kaiser from the School of Medicine at the University of Nottingham, looked at epilepsy patients undergoing surgery.

They found that changes in the local network within brain regions can be a better predictor ...

2021-05-20

More than 90 years ago, astronomer Edwin Hubble observed the first hint of the rate at which the universe expands, called the Hubble constant.

Almost immediately, astronomers began arguing about the actual value of this constant, and over time, realized that there was a discrepancy in this number between early universe observations and late universe observations.

Early in the universe's existence, light moved through plasma--there were no stars yet--and from oscillations similar to sound waves created by this, scientists deduced that the Hubble constant was about 67. This means the universe expands about 67 kilometers per second faster every 3.26 million light-years.

But this observation differs when scientists look at the universe's ...

2021-05-20

BOSTON - Dana-Farber Cancer Institute researchers are presenting dozens of research studies at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). The studies will be presented during the virtual program on June 4-8, 2021. ASCO is the world's largest clinical cancer research meeting, attracting more than 30,000 oncology professionals from around the world.

Toni K. Choueiri, MD, the director of the Lank Center for Genitourinary Oncology at Dana-Farber, will present results from the randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-564 trial evaluating pembrolizumab versus placebo after surgery in patients with renal cell carcinoma (abstract LBA5) during ASCO's Plenary Session on Sunday, June ...

2021-05-20

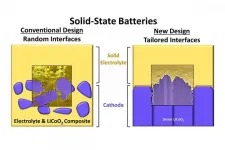

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Solid-state batteries pack a lot of energy into a small space, but their electrodes are not good at keeping in touch with their electrolytes. Liquid electrolytes reach every nook and cranny of an electrode to spark energy, but liquids take up space without storing energy and fail over time. Researchers are now putting solid electrolytes in touch with electrodes made of strategically arranged materials - at the atomic level - and the results are helping drive better solid-state battery technologies.

A new study, led by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign materials science and engineering professor Paul Braun, postdoctoral research associate Beniamin Zahiri, and Xerion Advanced Battery Corp. director of research and development ...

2021-05-20

The University of Maryland (UMD) co-published a new review paper in the Annual Review of Resource Economics to examine pollinators from both an economic and ecological perspective, providing much needed insight into the complexities of valuing pollination. Pollinators are not only a critical component of a healthy ecosystem, but they are also necessary to produce certain foods and boost crop yields. While native and wild pollinators (whether they be certain bee species, other insects and animals, or just the wind) still play an important role, managed honey bee colonies are commercially trucked around the U.S. to meet the need for pollination services in agricultural products. Recent reports of ...

2021-05-20

BATON ROUGE, Louisiana - A diet that improves the biomarkers of metabolic health, and that could potentially slow the aging process, has moved a step closer to reality.

"We've known for years that restricting the amino acid methionine in the diet produces immediate and lasting improvements in nearly every biomarker of metabolic health," said Thomas W. Gettys, PhD, Professor and Director, Nutrient Sensing and Adipocyte Signaling Laboratory at Pennington Biomedical Research Center. "The problem is that methionine-restricted diets have been difficult to implement because they taste so bad."

Until now. Restricting methionine normally involves diets formulated with elemental (e.g., individual) amino acids. Individual amino acids are the building blocks ...

2021-05-20

May 20, 2021 - Women with a history of weight cycling - losing and regaining 10 pounds or more, even once - have increased rates of insomnia and other sleep problems, reports a study in The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, official journal of the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"History of weight cycling was prospectively associated with several measures of poor sleep, including short sleep duration, worse sleep quality, greater insomnia, greater sleep disturbances, ...

2021-05-20

Melting glaciers and polar ice sheets are among the dominant sources of sea-level rise, yet until now, the water beneath them has remained hidden from airborne ice-penetrating radar.

With the detection of groundwater beneath Hiawatha Glacier in Greenland, researchers have opened the possibility that water can be identified under other glaciers from the air at a continental scale and help improve sea-level rise projections. The presence of water beneath ice sheets is a critical component currently missing from glacial melt scenarios that may greatly impact how quickly seas rise - for example, by enabling big chunks of ice to calve ...

2021-05-20

New research led by the University of Kent's School of Psychology has found that some brain activity methods used to detect incriminating memories do not work accurately in older adults.

Findings show that concealed information tests relying on electrical activity of the brain (electroencephalography [EEG]) are ineffective in older adults because of changes to recognition-related brain activity that occurs with aging.

EEG-based forensic memory detection is based on the logic that guilty suspects will hold incriminating knowledge about crimes they have committed, and therefore their brains will elicit a recognition response ...

2021-05-20

For the first time, researchers have successfully sequenced the entire genome from the skull of Peştera Muierii 1, a woman who lived in today's Romania 35,000 years ago. Her high genetic diversity shows that the out of Africa migration was not the great bottleneck in human development but rather this occurred during and after the most recent Ice Age. This is the finding of a new study led by Mattias Jakobsson at Uppsala University and being published in Current Biology.

"She is a bit more like modern-day Europeans than the individuals in Europe 5,000 years earlier, but the difference is much less than we had thought. We can see that she is not a direct ancestor of modern Europeans, but she is a predecessor of the hunter-gathers that lived in Europe until the end of the last ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] The driving force behind tropical mudslides

A Syracuse University Ph.D. candidate leads a research expedition in search of answers to erosion in his home country of Colombia