(Press-News.org) BATON ROUGE, Louisiana - A diet that improves the biomarkers of metabolic health, and that could potentially slow the aging process, has moved a step closer to reality.

"We've known for years that restricting the amino acid methionine in the diet produces immediate and lasting improvements in nearly every biomarker of metabolic health," said Thomas W. Gettys, PhD, Professor and Director, Nutrient Sensing and Adipocyte Signaling Laboratory at Pennington Biomedical Research Center. "The problem is that methionine-restricted diets have been difficult to implement because they taste so bad."

Until now. Restricting methionine normally involves diets formulated with elemental (e.g., individual) amino acids. Individual amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. But diets made from elemental amino acids taste bad, and few are willing to tolerate the regimen.

A palatable solution emerged from a collaboration between Dr. Gettys' lab and food scientists at LSU who developed the methods to selectively delete methionine from casein, the main protein in milk and cheese. Dr. Gettys' lab then conducted the proof-of-concept testing to establish that oxidized casein could be used to implement methionine restriction without the objectionable taste of the standard elemental diet.

More than two-thirds of Americans are overweight or have obesity. More than 40 percent of adults have prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

"A diet that offsets all the major components of metabolic disease would have an enormous impact on the nation's health, and the world's," said Han Fang, PhD, a Postdoctoral Researcher in Dr. Gettys' lab, and the lead author of the study.

A palatable, methionine-restricted diet could also ease a major frustration for those struggling to manage their weight. Each year, millions of people improve their metabolism and lose weight by reducing how much they eat. But eventually, most people gain back those pounds.

"Calorie restriction is an effective weight-management tool. But for most people it is also very, very difficult to follow long-term," said Pennington Biomedical Executive Director John Kirwan, PhD. "This struggle is one of the major reasons our scientists explore every avenue to find solutions to the obesity epidemic."

Although the oxidized casein diet represents a major advance, Gettys and his team say more research is needed. Their study, published in the journal iScience, involved mice. Translating the results to produce a methionine-restricted human diet, which is far more complex and involves multiple sources of protein, will be challenging.

In the short term, a practical solution may be to develop a palatable group of modified proteins to serve as the basis of a therapeutic diet. People would follow the diet for a limited period while under medical supervision.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award number R01 DK096311. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

About the Pennington Biomedical Research Center

The Pennington Biomedical Research Center is at the forefront of medical discovery as it relates to understanding the triggers of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer and dementia. The Center conducts basic, clinical, and population research, and is affiliated with Louisiana State University. The research enterprise at Pennington Biomedical includes over 450 employees within a network of 40 clinics and research laboratories, and 13 highly specialized core service facilities. Its scientists and physician/scientists are supported by research trainees, lab technicians, nurses, dietitians, and other support personnel. Pennington Biomedical is located in state-of-the-art research facilities on a 222-acre campus in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. For more information, see http://www.pbrc.edu.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center

6400 Perkins Road

Baton Rouge, LA 70808

May 20, 2021 - Women with a history of weight cycling - losing and regaining 10 pounds or more, even once - have increased rates of insomnia and other sleep problems, reports a study in The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, official journal of the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"History of weight cycling was prospectively associated with several measures of poor sleep, including short sleep duration, worse sleep quality, greater insomnia, greater sleep disturbances, ...

Melting glaciers and polar ice sheets are among the dominant sources of sea-level rise, yet until now, the water beneath them has remained hidden from airborne ice-penetrating radar.

With the detection of groundwater beneath Hiawatha Glacier in Greenland, researchers have opened the possibility that water can be identified under other glaciers from the air at a continental scale and help improve sea-level rise projections. The presence of water beneath ice sheets is a critical component currently missing from glacial melt scenarios that may greatly impact how quickly seas rise - for example, by enabling big chunks of ice to calve ...

New research led by the University of Kent's School of Psychology has found that some brain activity methods used to detect incriminating memories do not work accurately in older adults.

Findings show that concealed information tests relying on electrical activity of the brain (electroencephalography [EEG]) are ineffective in older adults because of changes to recognition-related brain activity that occurs with aging.

EEG-based forensic memory detection is based on the logic that guilty suspects will hold incriminating knowledge about crimes they have committed, and therefore their brains will elicit a recognition response ...

For the first time, researchers have successfully sequenced the entire genome from the skull of Peştera Muierii 1, a woman who lived in today's Romania 35,000 years ago. Her high genetic diversity shows that the out of Africa migration was not the great bottleneck in human development but rather this occurred during and after the most recent Ice Age. This is the finding of a new study led by Mattias Jakobsson at Uppsala University and being published in Current Biology.

"She is a bit more like modern-day Europeans than the individuals in Europe 5,000 years earlier, but the difference is much less than we had thought. We can see that she is not a direct ancestor of modern Europeans, but she is a predecessor of the hunter-gathers that lived in Europe until the end of the last ...

DURHAM, N.C. - A newly identified group of antibodies that binds to a coating of sugars on the outer shell of HIV is effective in neutralizing the virus and points to a novel vaccine approach that could also potentially be used against SARS-CoV-2 and fungal pathogens, researchers at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute report.

In a study appearing online May 20 in the journal Cell, the researchers describe an immune cell found in both monkeys and humans that produces a unique type of anti-glycan antibody. This newly described antibody has the ability to attach ...

Juvenile salmon migrating to the sea in the Sacramento River face a gauntlet of hazards in an environment drastically modified by humans, especially with respect to historical patterns of stream flow. Many studies have shown that survival rates of juvenile salmon improve as the amount of water flowing downstream increases, but "more is better" is not a useful guideline for agencies managing competing demands for the available water.

Now fisheries scientists have identified key thresholds in the relationship between stream flow and salmon survival that can serve as actionable targets for managing water resources in the Sacramento River. The new analysis, published May 19 in Ecosphere, revealed nonlinear ...

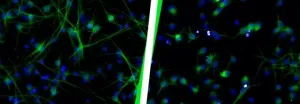

Today, proteins that can be controlled with light are a widely used tool in research to specifically switch certain functions on and off in living organisms. Channelrhodopsins are often used for the technique known as optogenetics: When exposed to light, these proteins open a pore in the cell membrane through which ions can flow in; this is how nerve cells can be activated. A team from the Centre for Protein Diagnostics (PRODI) at Ruhr-Universität Bochum has now used spectroscopy to discover a universal functional mechanism of channelrhodopsins that determines their efficiency as a channel and thus as an optogenetic tool. The researchers led by Professor Klaus ...

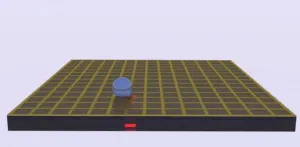

Microfluidic technologies have seen great advances over the past few decades in addressing applications such as biochemical analysis, pharmaceutical development, and point-of-care diagnostics. Miniaturization of biochemical operations performed on lab-on-a-chip microfluidic platforms benefit from reduced sample, reagent, and waste volumes, as well as increased parallelization and automation. This allows for more cost-effective operations along with higher throughput and sensitivity for faster and more efficient sample analysis and detection.

Optoelectrowetting (OEW) is a digital optofluidic technology that is based on the principles of light-controlled electrowetting and enables ...

Since our ancestors infected themselves with retroviruses millions of years ago, we have carried elements of these viruses in our genes - known as human endogenous retroviruses, or HERVs for short. These viral elements have lost their ability to replicate and infect during evolution, but are an integral part of our genetic makeup. In fact, humans possess five times more HERVs in non-coding parts than coding genes. So far, strong focus has been devoted to the correlation of HERVs and the onset or progression of diseases. This is why HERV expression has been studied in samples of pathological origin. Although important, these studies ...

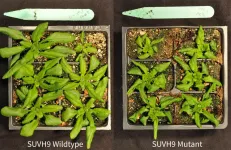

Passing down a healthy genome is a critical part of creating viable offspring. But what happens when you have harmful modifications in your genome that you don't want to pass down? Baby plants have evolved a method to wipe the slate clean and reinstall only the modifications that they need to grow and develop. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor & HHMI Investigator Rob Martienssen and his collaborators, Jean-Sébastien Parent and Institut de Recherche pour le Développement Université de Montpellier scientist Daniel Grimanelli, discovered one of the genes responsible for reinstalling modifications in a baby plant's genome.

A plant's genomic modifications--called epigenetic ...