(Press-News.org) Chronic skin itching drives more people to the dermatologist than any other condition. In fact, the latest science literature finds that 7% of U.S. adults, and between 10 and 20% of people in developed countries, suffer from dermatitis, a common skin inflammatory condition that causes itching.

"Itch is a significant clinical problem, often caused by underlying medical conditions in the skin, liver, or kidney. Due to our limited understanding of itch mechanisms, we don't have effective treatment for the majority of patients," said Liang Han, an assistant professor in the Georgia Institute of Technology's School of Biological Sciences who is also a researcher in the Parker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience.

Until recently, neuroscientists considered the mechanisms of skin itch the same. But Han and her research team recently uncovered differences in itch in non-hairy versus hairy areas of the skin, opening new areas for research.

Their research, published April 13 in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America), could open new, more effective treatments for patients suffering from persistent skin itching.

Itch Origins More Than Skin Deep

According to researchers, there are two different types of stimuli from the nervous system that trigger the itch sensation through sensory nerves in the skin ? chemical and mechanical. In their study, Han and her team identified a specific neuron population that controls itching in 'glabrous' skin ?the smoother, tougher skin that's found on the palms of hands and feet soles.

Itching in those areas poses greater difficulty for sufferers and is surprisingly common. In the U.S., there are an estimated 200,000 cases a year of dyshidrosis, a skin condition causing itchy blisters to develop only on the palm and soles. Another chronic skin condition, palmoplantar pustulosis (a type of psoriasis that causes inflamed, scaly skin and intense itch on the palms and soles), affects as many as 1.6 million people in the U.S. each year.

"That's actually one of the most debilitating places (to get an itch)," said first author Haley R. Steele, a graduate student in the School of Biological Sciences. "If your hands are itchy, it's hard to grasp things, and if it's your feet, it can be hard to walk. If there's an itch on your arm, you can still type. You'll be distracted, but you'll be OK. But if it's your hands and feet, it's harder to do everyday things."

Ability to Block, Activate Itch-causing Neurons in Lab Mice

Since many biological mechanisms underlying itch -- such as receptors and nerve pathways -- are similar in mice and people, most itch studies rely on mice testing. Using mice in their lab, Georgia Tech researchers were able to activate or block these neurons.

The research shows, for the first time, "the actual neurons that send itch are different populations. Neurons that are in hairy skin that do not sense itch in glabrous skins are one population, and another senses itch in glabrous skins."

Why has an explanation so far eluded science? "I think one reason is because most of the people in the field kind of assumed it was the same mechanism that's controlling the sensation. It's technically challenging. It's more difficult than working on hairy skin," Han said.

To overcome this technical hurdle, the team used a new investigative procedure, or assay, modeled after human allergic contact dermatitis, Steele said.

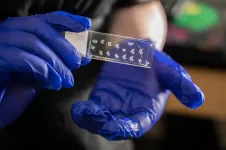

The previous method would have involved injecting itch-causing chemicals into mice skin, but most of a mouse's skin is covered with hair. The team had to focus on the smooth glabrous skin on tiny mice hands and feet. Using genetically modified mice also helped identify the right sensory neurons responsible for glabrous skin itches.

"We activated a particular set of neurons that causes itch, and we saw that biting behavior again modeled," said Steele, referring to how mice usually deal with itchy skin.

One set of study mice was given a chemical to specifically kill an entire line of neurons. Focusing on three previously known neuron mechanisms related to itch sensation found in hairy skin, they found that two of the neurons, MrgprA3+ and MrgprD+, did not play important roles in non-hairy skin itch, but the third neuron, MrgprC11+, did. Removing it reduced both acute and chronic itching in the soles and palms of test mice.

Potential to Drive New Treatments for Chronic Itch

Han's team hopes that the research leads to treatments that will turn off those itch-inducing neurons, perhaps by blocking them in human skin.

"To date, most treatments for skin itch do not discriminate between hairy and glabrous skin except for potential medication potency due to the increased skin thickness in glabrous skin," observed Ron Feldman, assistant professor in the Department of Dermatology in the Emory University School of Medicine. Georgia Tech's findings "provide a rationale for developing therapies targeting chronic itching of the hands and feet that, if left untreated, can greatly affect patient quality of life," he concluded.

What's next for Han and her team? "We would like to investigate how these neurons transmit information to the spinal cord and brain," said Han, who also wants to investigate the mechanisms of chronic itch conditions that mainly affect glabrous skin such as cholestatic itch, or itch due to reduced or blocked bile flow often seen in liver and biliary system diseases.

"I joined this lab because I love working with Liang Han," added Steele, who selected glabrous skin itch research for her Ph.D. "because it was the most technically challenging and had the greatest potential for being really interesting and significant to the field."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Pfizer Aspire Dermatology Award to Liang Han.

CITATION: H. Steele, et al., "MrgprC11+ sensory neurons mediate glabrous skin itch." (PNAS, 2021) https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022874118

The Georgia Institute of Technology, or Georgia Tech, is a top 10 public research university developing leaders who advance technology and improve the human condition.

The Institute offers business, computing, design, engineering, liberal arts, and sciences degrees. Its nearly 40,000 students representing 50 states and 149 countries, study at the main campus in Atlanta, at campuses in France and China, and through distance and online learning.

As a leading technological university, Georgia Tech is an engine of economic development for Georgia, the Southeast, and the nation, conducting more than $1 billion in research annually for government, industry, and society.

When Charles Darwin published Descent of Man 150 years ago, he launched scientific investigations on human origins and evolution. This week, three leading scientists in different, but related disciplines published "Modern theories of human evolution foreshadowed by Darwin's Descent of Man," in Science, in which they identify three insights from Darwin's opus on human evolution that modern science has reinforced.

"Working together was a challenge because of disciplinary boundaries and different perspectives, but we succeeded," said Sergey Gavrilets, lead author and professor in the Departments of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Mathematics at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Their goal with this review summary was to apply the framework ...

CLEVELAND - Follow-up data from the landmark SPRINT study of the effect of high blood pressure on cardiovascular disease have confirmed that aggressive blood pressure management -- lowering systolic blood pressure to less than 120 mm Hg -- dramatically reduces the risk of heart disease, stroke, and death from these diseases, as well as death from all causes, compared to lowering systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mm Hg. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the upper number in the blood pressure measurement, 140/90, for example.

In findings published in the May 20, 2021 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, investigators presented new evidence of the effectiveness of reducing SBP to a target range of less than 120 ...

Depressive disorders are among the most frequent illnesses worldwide. The causes are complex and to date only partially understood. The trace element lithium appears to play a role. Using neutrons of the research neutron source at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), a research team has now proved that the distribution of lithium in the brains of depressive people is different from the distribution found in healthy humans.

Lithium is familiar to many of us from rechargeable batteries. Most people ingest lithium on a daily basis in drinking water. International studies have shown that ...

Beijing, 19 May 2021: the journal Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications (CVIA) has just published a new issue, Volume 5 Issue 4.

This issue brings together important research from leading cardiologists in US and China in a combination of reviews, original research and case reports.

REVIEWS

Pei Huang, Yi Zhang, Yi Tang, Qinghua Fu, Zhaofen Zheng, Xiaoyan Yang and Yingli Yu

Progress in the Study of the Left Atrial Function Index in Cardiovascular Disease:

A Literature Review (https://tinyurl.com/3vruva37)

Nikhil H. Shah, Steven J. Ross, Steve A. Noutong Njapo, Justin Merritt, Andrew Kolarich, Michael Kaufmann, ...

Social scientists have had a longstanding fixation on moral character, demographic information, and socioeconomic status when it comes to analyzing crime and arrest rates. The measures have become traditional markers used to quantify and predict criminalization, but they leave out a crucial indicator: what's going on in the changing world around their subjects.

An unprecedented longitudinal study, published today in the American Journal of Sociology, looks to make that story more complete and show that when it comes to arrests it can come down to when someone is rather than who someone is, a theory the researchers refer to as the birth lottery of history.

Harvard sociologist Robert J. Sampson and Ph.D. candidate Roland Neil followed arrests in the lives of more than ...

Paleontologists had to adjust to stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many had to postpone fossil excavations, temporarily close museums and teach the next generation of fossil hunters virtually instead of in person.

But at least parts of the show could go on during the pandemic -- with some significant changes.

"For paleontologists, going into the field to look for fossils is where data collection begins, but it does not end there," said Christian Sidor, a University of Washington professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology ...

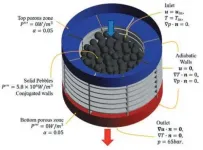

When one of the largest modern earthquakes struck Japan on March 11, 2011, the nuclear reactors at Fukushima-Daiichi automatically shut down, as designed. The emergency systems, which would have helped maintain the necessary cooling of the core, were destroyed by the subsequent tsunami. Because the reactor could no longer cool itself, the core overheated, resulting in a severe nuclear meltdown, the likes of which haven't been seen since the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.

Since then, reactors have improved exponentially in terms of safety, sustainability and efficiency. Unlike the light-water reactors at Fukushima, which had liquid coolant and uranium ...

"Abominable mystery" -- the early origin and evolution of angiosperms (flowering plants) was such described by Charles Robert Darwin. So far, we still have not completely solved the problem, and do not know how the earth evolved into such a colorful and blooming world.

Recently, a new angiosperm was reported based on numerous exceptionally well-preserved fossils from the Lower Cretaceous of Jiuquan Basin, West Gansu Province, Northwest China. The new discovery is the earliest and unique record of early angiosperms in Northwest China. The study has been accepted for publication in the journal National Science Review and is currently available online at https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwab084.

The new angiosperm was named Gansufructus saligna, and all the fossil specimens ...

Atmospheric ozone, which can regulate the amount of incoming ultraviolet radiation on the Earth's surface, is important for the atmospheric environment and ecosystems. Tropospheric ozone, primarily originating from photochemical reactions, is the third most prominent greenhouse gas causing climate warming.

A research team led by Dr. Jinqiang Zhang from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences tried to analyze vertical ozone distributions and explore the influence of deep stratospheric intrusions and wildfires on ozone variation in the northern Tibetan Plateau (TP) during the Asian summer monsoon period.

Their findings were published in Atmospheric Research.

Ozone variation over the TP can influence weather and climate change. ...

Researchers from the University of Surrey have revealed a new method that enables common laboratory scanning electron microscopes to see graphene growing over a microchip surface in real time.

This discovery, published in ACS Applied Nano Materials, could create a path to control the growth of graphene in production factories and lead to the reliable production of graphene layers.

Dispensing with the use of expensive bespoke systems, the new technique not only produces graphene sheets reliably but also allows to use fast-acting catalysts that reduce growth times from several hours to only a few minutes.

With the use of video imagining, the team from Surrey's Advanced Technology Institute (ATI) have shown graphene growing over an iron catalyst, using a silicon nitride ...