(Press-News.org) Paleontologists had to adjust to stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many had to postpone fossil excavations, temporarily close museums and teach the next generation of fossil hunters virtually instead of in person.

But at least parts of the show could go on during the pandemic -- with some significant changes.

"For paleontologists, going into the field to look for fossils is where data collection begins, but it does not end there," said Christian Sidor, a University of Washington professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the UW's Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture. "After you collect fossils, you have to bring them to the laboratory, clean them off and see what you've found."

Among other adaptations during the pandemic, Sidor and his UW colleagues have spent more time cleaning, preparing and analyzing fossils excavated before the pandemic, as well as managing new pandemic-related struggles -- such as a misplaced shipment of irreplaceable specimens.

For Sidor's team, a recent triumph came from an analysis -- led by UW postdoctoral researcher Bryan Gee -- of fossils of Micropholis stowi, a salamander-sized amphibian that lived in the Early Triassic, shortly after Earth's largest mass extinction approximately 252 million years ago, at the end of the Permian Period. Micropholis is a temnospondyl, a group of extinct amphibians known from fossil deposits around the globe. In a paper published May 21 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Gee and Sidor report on the first occurrence of Micropholis in ancient Antarctica.

"Previously, Micropholis was only known from South African specimens," said Gee. "That isolation was considered fairly typical for amphibians in the Southern Hemisphere during the Early Triassic. Each region -- South Africa, Madagascar, Antarctica, Australia -- will have its own set of amphibian species. Now, we're seeing that Micropholis was more widespread than previously recognized."

Out of more than 30 Early Triassic amphibians in the Southern Hemisphere, Micropholis is now only the second found in more than one region, according to Gee. That is surprising given Earth's geography. In the Early Triassic, most of Earth's continents were connected as a part of a single, large landmass, Pangea. Places like South Africa and Antarctica were not as far apart as they are today, and may have had similar climates. Some scientists theorize that these closely placed regions could harbor different amphibian species as a consequence of the end-Permian mass extinction.

"It had been proposed that there were only small populations of survivors and low movement of species in the Early Triassic, which could have explained these regional differences," said Gee.

Finding Micropholis in two regions may indicate that this species was a "generalist" -- adaptable to many types of environments -- and could easily spread after the mass extinction.

Alternatively, it's possible that many other amphibians actually lived in multiple regions, like Micropholis, but paleontologists haven't found evidence yet. While some Southern Hemisphere regions like South Africa have been well sampled, others have not -- like Antarctica, which in the Early Triassic was relatively temperate, but is today largely covered by ice sheets.

Sidor's team collected skulls and other fragile body parts from four individuals of Micropholis during a 2017-2018 collection trip to the Transantarctic Mountains. In 2019, Gee agreed to come to the UW to lead the analysis of amphibian fossils from that trip after completing his doctoral degree at the University of Toronto. He completed his degree early in the pandemic and moved to Seattle during the second wave of COVID-19.

With social distancing measures in place on campus, Sidor delivered the fossils and a microscope to Gee's home, where he analyzed the specimens in his living room.

"Having access to the microscope was really the most essential piece of equipment, to be able to identify all the small-scale anatomical features that we need to definitively prove these were Micropholis fossils," said Gee.

On the same trip, Sidor's team collected another rare find: a well-preserved skull of a therocephalian, a group of extinct mammal relatives that lived in the Permian and Triassic periods. Therocephalians were a widespread group of both herbivores and carnivores.

"But the Antarctic record for these animals is very poor," said Sidor. "So this was a rare find."

It was a rare find that nearly went extinct again. Sidor shipped the therocephalian skull in October 2019 to Chicago's Field Museum, where it was cleaned and prepped by his longtime colleague Akiko Shinya.

"Not being able to travel to museums to do research, we've been shipping fossils to each other -- which we don't like to do, but sometimes we have to in order to keep the work going," said Sidor.

In early April, Shinya shipped the finished specimens overnight back to Sidor in Seattle, but the package did not show up at the projected time. As Sidor recounted on Twitter, the skull was apparently lost in a transfer facility in Indiana -- he feared for good. After several days, the package was found, and was promptly transported to Seattle and delivered safely to the UW.

"I was so relieved," said Sidor. "When I thought it was lost, I had been thinking about the insurance forms. How do you put a dollar value on a specimen that you needed an LC-130 Hercules to collect?"

The skull is undergoing analysis at the UW. As for the Antarctic Micropholis specimens, they'll soon receive a new home. Later this year, they'll go on display at the Burke Museum.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

For more information, contact Sidor at casidor@uw.edu and Gee at bmgee@uw.edu.

Grant numbers: ANT-1341304, ANT-1947094

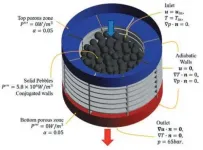

When one of the largest modern earthquakes struck Japan on March 11, 2011, the nuclear reactors at Fukushima-Daiichi automatically shut down, as designed. The emergency systems, which would have helped maintain the necessary cooling of the core, were destroyed by the subsequent tsunami. Because the reactor could no longer cool itself, the core overheated, resulting in a severe nuclear meltdown, the likes of which haven't been seen since the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.

Since then, reactors have improved exponentially in terms of safety, sustainability and efficiency. Unlike the light-water reactors at Fukushima, which had liquid coolant and uranium ...

"Abominable mystery" -- the early origin and evolution of angiosperms (flowering plants) was such described by Charles Robert Darwin. So far, we still have not completely solved the problem, and do not know how the earth evolved into such a colorful and blooming world.

Recently, a new angiosperm was reported based on numerous exceptionally well-preserved fossils from the Lower Cretaceous of Jiuquan Basin, West Gansu Province, Northwest China. The new discovery is the earliest and unique record of early angiosperms in Northwest China. The study has been accepted for publication in the journal National Science Review and is currently available online at https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwab084.

The new angiosperm was named Gansufructus saligna, and all the fossil specimens ...

Atmospheric ozone, which can regulate the amount of incoming ultraviolet radiation on the Earth's surface, is important for the atmospheric environment and ecosystems. Tropospheric ozone, primarily originating from photochemical reactions, is the third most prominent greenhouse gas causing climate warming.

A research team led by Dr. Jinqiang Zhang from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences tried to analyze vertical ozone distributions and explore the influence of deep stratospheric intrusions and wildfires on ozone variation in the northern Tibetan Plateau (TP) during the Asian summer monsoon period.

Their findings were published in Atmospheric Research.

Ozone variation over the TP can influence weather and climate change. ...

Researchers from the University of Surrey have revealed a new method that enables common laboratory scanning electron microscopes to see graphene growing over a microchip surface in real time.

This discovery, published in ACS Applied Nano Materials, could create a path to control the growth of graphene in production factories and lead to the reliable production of graphene layers.

Dispensing with the use of expensive bespoke systems, the new technique not only produces graphene sheets reliably but also allows to use fast-acting catalysts that reduce growth times from several hours to only a few minutes.

With the use of video imagining, the team from Surrey's Advanced Technology Institute (ATI) have shown graphene growing over an iron catalyst, using a silicon nitride ...

Sloughed off skin and bodily fluids are things most people would prefer to avoid.

But for marine biologist like Cheryl Lewis Ames, Associate Professor of Applied Marine Biology in the Graduate School of Agricultural Science at Tohoku University (Japan), such remnants of life have become a magical key to detecting the unseen.

Any organism living in the ocean will inevitably leave behind traces containing their DNA - environmental DNA (eDNA) - detectable in water samples collected from the ocean

Only recently has molecular sequencing technology become ...

Researchers at the University of Zurich show how climate mitigation scenarios can be improved by taking into account that the financial system can play both an enabling or a hampering role on the path to a sustainable economic system.

To limit global warming, a profound transformation of energy, production and consumption in our economies is required. The scale of the transformation means that the financial system must have a proactive role. New green investments are needed, as well as a reallocation of capital from high to low-carbon activities. The Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial ...

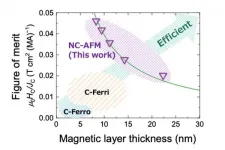

Researchers at Tohoku University and the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) have discovered a new spintronic phenomenon - a persistent rotation of chiral-spin structure.

Their discovery was published in the journal Nature Materials on May 13, 2021.

Tohoku University and JAEA researchers studied the response of chiral-spin structure of a non-collinear antiferromagnet Mn3Sn thin film to electron spin injection and found that the chiral-spin structure shows persistent rotation at zero magnetic field. Moreover, their frequency can be tuned by the applied current.

"The electrical control of magnetic ...

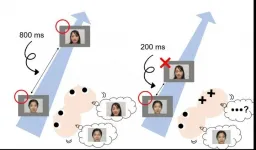

It has previously been reported that human visual system has a temporal limitation in processing visual information when perceiving things that occur less than half a second apart. This temporal deficit is known as "attentional blink" and has been demonstrated in a large number of studies. These studies reported that adults could recognize two things when these two were temporally separated over 500 ms, but adults overlooked the second thing when the temporal interval was less than 500 ms. Recently, this attentional blink phenomenon has been observed in even preverbal infants less than one-year old.

In the study ...

Finnish researchers have been the first to determine the cause for the nonsyndromic early-onset hereditary canine hearing loss in Rottweilers. The gene defect was identified in a gene relevant to the sense of hearing. The study can also promote the understanding of mechanisms of hearing loss in human.

Hearing loss is the most common sensory impairment and a complex problem in humans, with varying causes, severity and age of onset. Deafness and hearing loss are fairly common also in dogs, but gene variants underlying the hereditary form of the disorder are so far poorly ...

If you've been to your local beach, you may have noticed the wind tossing around litter such as an empty potato chip bag or a plastic straw. These plastics often make their way into the ocean, affecting not only marine life and the environment but also threatening food safety and human health.

Eventually, many of these plastics break down into microscopic sizes, making it hard for scientists to quantify and measure them. Researchers call these incredibly small fragments "nanoplastics" and "microplastics" because they are not visible to the naked eye. Now, in a multiorganizational effort led by the National Institute of Standards and ...