(Press-News.org) If you've been to your local beach, you may have noticed the wind tossing around litter such as an empty potato chip bag or a plastic straw. These plastics often make their way into the ocean, affecting not only marine life and the environment but also threatening food safety and human health.

Eventually, many of these plastics break down into microscopic sizes, making it hard for scientists to quantify and measure them. Researchers call these incredibly small fragments "nanoplastics" and "microplastics" because they are not visible to the naked eye. Now, in a multiorganizational effort led by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC), researchers are turning to a lower part of the food chain to solve this problem.

The researchers have developed a novel method that uses a filter-feeding marine species to collect these tiny plastics from ocean water. The team published its findings as a proof-of-principle study in the scientific journal Microplastics and Nanoplastics.

Plastics consist of synthetic materials known as polymers that are usually made from petroleum and other fossil fuels. Each year more than 300 million tons of plastics are produced, and 8 million tons end up in the ocean. The most common kinds of plastics found in marine environments are polyethylene and polypropylene. Low-density polyethylene is commonly used in plastic grocery bags or six-pack rings for soda cans. Polypropylene is commonly used in reusable food containers or bottle caps.

"Sunlight and other chemical and mechanical processes cause these plastic objects to become smaller and smaller," said NIST researcher Vince Hackley. "With time they change their shape and maybe even their chemistry."

While there isn't an official definition for these smaller nanoplastics, researchers generally describe them as being artificial products that the environment breaks down into microscopic pieces. They're typically the size of one millionth of a meter (one micrometer, or a micron) or smaller.

These tiny plastics pose many potential hazards to the environment and food chain. "As plastic materials degrade and become smaller, they are consumed by fish or other marine organisms like mollusks. Through that path they end up in the food system, and then in us. That's the big concern," said Hackley.

For help in measuring nanoplastics, researchers turned to a group of marine species known as tunicates, which process large volumes of water through their bodies to get food and oxygen -- and, unintentionally, nanoplastics. What makes tunicates so useful to this project is that they can ingest nanoplastics without affecting the plastics' shapes or size.

For their study, researchers chose a tunicate species known as C. robusta because "they have a good retention efficiency for micro- and nanoparticles," said European Commission researcher Andrea Valsesia. The researchers obtained live specimens of the species as part of a collaboration with the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology and the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn research institute, both in Naples, Italy.

The tunicates were exposed to different concentrations of polystyrene, a versatile plastic, in the form of nanosize particles. The tunicates were then harvested and then went through a chemical digestion process, which separated the nanoplastics from the organisms. However, during this stage some residual organic compounds digested by the tunicate were still mixed in with the nanoplastics, possibly interfering with the purification and analysis of the plastics.

So, researchers used an additional isolation technique called asymmetrical-flow field flow fractionation (AF4) to separate the nanoplastics from the unwanted material. The separated or "fractionated" nanoplastics could then be collected for further analysis. "That is one of the biggest issues in this field: the ability to find these nanoplastics and isolate and separate them from the environment they exist in," said Valsesia.

The nanoplastic samples were then placed on a specially engineered chip, designed so that the nanoplastics formed clusters, making it easier to detect and count them in the sample. Lastly, the researchers used Raman spectroscopy, a noninvasive laser-based technique, to characterize and identify the chemical structure of the nanoplastics.

The special chips provide advantages over previous methods. "Normally, using Raman spectroscopy for identifying nanoplastics is challenging, but with the engineered chips researchers can overcome this limitation, which is an important step for potential standardization of this method," said Valsesia. "The method also enables detection of the nanoplastics in the tunicate with high sensitivity because it concentrates the nanoparticles into specific locations on the chip."

The researchers hope this method can lay the foundation for future work. "Almost everything we're doing is at the frontier. There are no widely adopted methods or measurements," said Hackley. "This study on its own is not the end point. It's a model for how to do things going forward."

Among other possibilities, this approach might pave the way for using tunicates to serve as biological indicators of an ecosystem's health. "Scientists might be able to analyze tunicates in a particular spot to look at nanoplastic pollution in that area," said Jérémie Parot, who worked on this study while at NIST and is now at SINTEF Industry, a research institute in Norway.

The NIST and JRC researchers continue to work together through a collaboration agreement and hope it will provide additional foundations for this field, such as a reference material for nanoplastics. For now, the group's multistep methodology provides a model for other scientists and laboratories to build on. "The most important part of this collaboration was the opportunity to exchange ideas for how we can do things going forward together," said Hackley.

INFORMATION:

Just half a degree Celsius less warming would save economic losses of Chinese railway infrastructure by approximately $0.63 billion per year, according to a new paper published by a collaborative research team based in Beijing Normal University and the Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China.

The study, which appears in Transportation Research Part D recently, found that the rainfall-induced disaster risk of railway infrastructure has increased with increasing extreme rainfall days during the decades 1981-2016. Limiting global ...

Ending our dependence on coal is essential for effective climate protection. Nevertheless, efforts to phase out coal trigger anxiety and resistance, particularly in mining regions. The governments of both Canada and Germany have involved various stakeholders to develop recommendations aimed at delivering just transitions and guiding structural change. In a new study, researchers at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) compare the stakeholder commissions convened by the two countries, drawing on expert interviews with their members, and examine how governments use commissions to legitimize their transition policies.

In the study, the researchers identify similarities and ...

The work, carried out by Pilar Madrigal and Sandra Jurado, from the UMH-CSIC Neurosciences Institute in Alicante, a joint center of the Spanish National Research Council and Miguel Hernández University, has been published in Communications Biology, a Nature group´s journal.

"Our in-depth analysis of the oxytocin-vasopressin circuit in the mouse brain has revealed that these two molecules have distinct dynamics throughout embryonic development. It is likely that these adaptations modulate the functional properties of different brain regions according to their developmental stage, contributing to the refinement ...

Scientists of Tomsk Polytechnic University have developed a nanosensor-based hardware and software complex for measurement of cardiac micropotential energies without filtering and averaging-out cardiac cycles in real time. The device allows registering early abnormalities in the function of cardiac muscle cells, which otherwise can be recorded only during open-heart surgery or by inserting an electrode in a cardiac cavity through a vein. Such changes can lead to sudden cardiac death (SCD). Nowadays, there are no alternatives to the Tomsk device for a number of key characteristics in Russia and the world. The research findings of four-year measurement of cardiac micropotential energies using this device ...

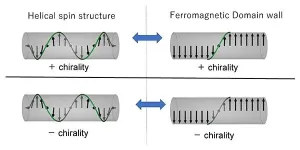

Using magnets, a collaborative group have furthered our understanding of chirality.

Their research was published in the journal Physical Review Letters on April 28, 2021.

Chirality is the lack of symmetry in matter. Human hands, for example, express chirality. A mirror image of your right hand differs from your left, giving it two distinguishable chiral states.

Chirality is an important issue in a myriad of scientific fields, ranging from high-energy physics to biology.

Within our bodies, some molecules, such as amino acids, show only one chiral state. In other words, they are homo-chiral. It is crucial to understand how this information is transferred and ...

Type 2 diabetes patients who also have asthma are benefitting from a diabetes medication, typically given to help the pancreas produce more insulin, that also improves asthma symptoms and may reduce lung and airway inflammation.

These types of medication -- GLP-1 receptor agonists -- are a newer class of FDA-approved therapeutics that are generally used in addition to metformin for control of blood sugar or to induce weight loss in patients with obesity.

Researchers from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School and University Hospital Zurich in Switzerland used electronic health record (EHR) data of patients with asthma and type 2 diabetes who initiated treatment with GLP-1R agonists, finding lower rates of asthma exacerbations ...

'Don't forget the mask' - although most people nowadays follow this advice, professionals express different opinions about the effectiveness of face masks. An international team led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany, has now used observational data and model calculations to answer open questions. The study shows under which conditions and in which way masks actually reduce individual and population-average risks of being infected with COVID-19 and help mitigate the corona pandemic. In most environments and situations, ...

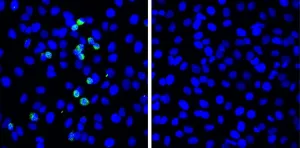

PHILADELPHIA--A five-year community outreach and engagement effort by the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania (ACC) to increase enrollment of Black patients into cancer clinical trials more than doubled the percentage of participants, improving access and treatment for a group with historically low representation in cancer research. The percentage of patients enrolled into a treatment clinical trial, for example, increased from 12 to 24 percent. A significant increase was also observed in non-therapeutic interventional and non-interventional trials.

The findings were published today in an abstract to be presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting on June 5. (Abstract #100). [ADD ...

New York, NY (May 21, 2021) --Women who were highly exposed to ultra-fine particles in air pollution during their pregnancy were more likely to have children who developed asthma, according to a study published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine in May. This is the first time asthma has been linked with prenatal exposure to this type of air pollution, which is named for its tiny size and which is not regulated or routinely monitored in the United States.

Slightly more than 18 percent of the children born to these mothers developed asthma in their preschool years, compared ...

Scientists from Hokkaido University have discovered a novel defensive response to SARS-CoV-2 that involves the viral pattern recognition receptor RIG-I. Upregulating expression of this protein could strengthen the immune response in COPD patients.

In the 18 months since the first report of COVID-19 and the spread of the pandemic, there has been a large amount of research into understanding it and developing menas to treat it. COVID-19 does not affect all infected individuals equally. Many individuals are asymptomatic; of those who are symptomatic, the large majority have mild symptoms, and only a small number have severe cases. The reasons for this are not fully understood and are an important area of ongoing research.

A team of scientists ...