(Press-News.org) A new study by University of Liverpool ecologists warns that heat-induced male infertility will see some species succumb to the effects of climate change earlier than thought.

Currently, scientists are trying to predict where species will be lost due to climate change so they can plan effective conservation strategies. However, research on temperature tolerance has generally focused on the temperatures that are lethal to organisms, rather than the temperatures at which organisms can no longer breed.

Published in Nature Climate Change, the study of 43 fruit fly (Drosophila) species showed that in almost half of the species, males became sterile at lower than lethal temperatures. Importantly, the worldwide distribution of these species could be predicted much more accurately by including the temperature at which they become sterile, rather than just using their lethal temperature. To give an example, Drosophila lummei males are sterile four degrees below their lethal limit. To put that in context, four degrees is the temperature difference between summer in northern England and the south of France.

Dr Steven Parratt, lead researcher from the University of Liverpool, said: "Our findings strongly suggest that where species can survive in nature is determined by the temperature at which males become sterile, not the lethal temperature.

"Unfortunately, we do not have any way to tell which organisms are fertile up to their lethal temperature, and which will be sterilised at cooler temperatures. So, a lot of species may have a hidden vulnerability to high temperatures that has gone unnoticed. This will make conservation more difficult, as we may be overestimating how well many species will do as the planet warms."

The researchers went on to model this for one of the Drosophila species using temperature predictions for 2060 and found more than half of areas with temperatures cool enough to survive will be too hot for the males to remain fertile.

Dr Tom Price, senior researcher from the University of Liverpool, commented: "Our work emphasises that temperature-driven fertility losses may be a major threat to biodiversity during climate change. We already had reports of fertility losses at high temperature in everything from pigs to ostriches, to fish, flowers, bees, and even humans. Unfortunately, our research suggests they are not isolated cases, and perhaps half of all species will be vulnerable to thermal infertility.

"We now urgently need to understand the range of organisms likely to suffer thermal fertility losses in nature, and the traits that predict vulnerability. We must understand the underlying genetics and physiology, so we can predict which organisms are vulnerable, and perhaps produce breeds of livestock more robust to these challenges."

Head of Terrestrial Ecosystems at the Natural Environment Research Council Dr Simon Kerley said: "This is a highly exciting piece of work that turns on its head our thinking and assumption of the role, rate, and impact of climate change. It really starts to shed light on the hidden and subtle impact of the changing conditions on the myriad of animals that we perhaps take for granted and have not previously considered 'at risk' from our changing climate. Importantly, it alerts us to the understanding this risk could occur sooner than we thought.

"This piece of work takes biology, at its most fundamental level, and explores it in a well-known and understood laboratory animal, but then takes that crucial extra step of relating it to the real world and the potential impact if may have on global biodiversity.

"With the COP15 and COP26 conferences taking place this year, this study serves as a timely reminder of the need to research and better understand the relationship between climate change and biodiversity loss. The Natural Environmental Research Council will continue to fund this vital research, and UKRI as a whole will work as part of the global effort to safeguard the natural environment for generations to come."

The study involved collaborators from the University of Leeds, University of Melbourne, University of Zürich and Stockholm University and was funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

INFORMATION:

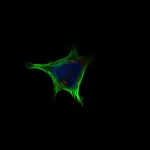

When a single gene in a cell is turned on or off, its resulting presence or absence can affect the function and survival of the cell. In a new study appearing May 24 in Nature Neuroscience, UCSF researchers have successfully catalogued this effect in the human neuron by separately toggling each of the 20,000 genes in the human genome.

In doing so, they've created a technique that can be employed for many different cell types, as well as a database where other researchers using the new technique can contribute similar knowledge, creating a picture of gene function in disease across the entire spectrum of human cells.

"This is the key next step in uncovering the mechanisms behind disease genes," said Martin Kampmann, PhD, associate professor, Institute ...

New research from Florida State University shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said FSU postdoctoral fellow Jon Hawkings. "And that's leading us to look now at a whole host of other questions such as how that mercury could potentially get into the food chain."

The study was published today in Nature Geoscience.

Initially, researchers sampled waters from three different ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- New research shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said Jon Hawkings, a postdoctoral researcher at Florida State University and and the German Research Centre for Geosciences. ...

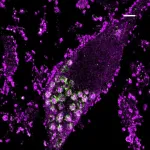

Plants grown in soil are colonized by diverse microbes collectively known as the plant microbiota, which is essential for optimal plant growth in nature and protects the plant host from the harmful effects of pathogenic microorganisms and insects. However, in the face of an advanced plant immune system that has evolved to recognize microbial associated-molecular patterns (MAMPs) - conserved molecules within a microbial class - and mount an immune response, it is unknown how soil-dwelling microbes are able to colonize plant roots. Now, MPIPZ researchers led by Paul Schulze-Lefert, and researchers from the University of Carolina led by Jeffery L. Dangl show, in two separate studies, that a subset ...

Brain tumor cells with a certain common mutation reprogram invading immune cells. This leads to the paralysis of the body's immune defense against the tumor in the brain. Researchers from Heidelberg, Mannheim, and Freiburg discovered this mechanism and at the same time identified a way of reactivating the paralyzed immune system to fight the tumor. These results confirm that therapeutic vaccines or immunotherapies are more effective against brain tumors if active substances are simultaneously used to promote the suppressed immune system.

Diffuse gliomas are usually incurable brain tumors that spread in the brain and are difficult to completely remove by surgery. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy often only have a limited ...

Scientists and clinicians at UCL and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) studying the effectiveness of CAR T-cell therapies in children with leukaemia, have discovered a small sub-set of T-cells that are likely to play a key role in whether the treatment is successful.

Researchers say 'stem cell memory T-cells' appear critical in both destroying the cancer at the outset and for long term immune surveillance and exploiting this quality could improve the design and performance of CAR T therapies.

Explaining the study, published in Nature Cancer, lead author Dr Luca Biasco (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health), said: "During clinical trials we have seen some very encouraging results in young patients with leukaemia, however it's still not clear why CAR T-cells continue ...

A population of bridled nailtail wallabies in Queensland has been brought back from the brink of extinction after conservation scientists led by UNSW Sydney successfully trialled an intervention technique never before used on land-based mammals.

Using a method known as 'headstarting', the researchers rounded up bridled nailtail wallabies under a certain size and placed them within a protected area where they could live until adulthood without the threat of their main predators - feral cats - before being released back into the wild.

In an article published today in Current Biology, the scientists describe how they decided on the strategy to protect only the juvenile wallabies from feral cats in Avocet Nature Refuge, ...

Knowledge systems outside of those sanctioned by Western universities have often been marginalised or simply not engaged with in many science disciplines, but there are multiple examples where Western scientists have claimed discoveries for knowledge that resident experts already knew and shared. This demonstrates not a lack of knowledge itself but rather that, for many scientists raised in Western society, little education concerning histories of systemic oppression has been by design. Western scientific knowledge has also been used to justify social and environmental control, including dispossessing colonised people of their ...

Our brain is usually well protected from uncontrolled influx of molecules from the periphery thanks to the blood-brain barrier, a physical seal of cells lining the blood vessel walls. The hypothalamus, however, is a notable exception to this rule. Characterized by "leaky" blood vessels, this region, located at the base of the brain, is exposed to a variety of circulating bioactive molecules. This anatomical feature also determines its function as a rheostat involved in the coordination of energy sensing and feeding behavior.

Several hormones and nutrients are known to influence the feeding neurocircuit in the hypothalamus. Classic examples are leptin and insulin, both involved in informing the brain of available energy. In the last years, the ...

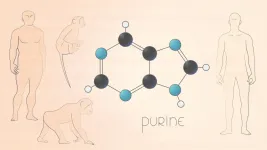

Skoltech scientists and their colleagues from Germany and the United States have analyzed the metabolomes of humans, chimpanzees, and macaques in muscle, kidney, and three different brain regions. The team discovered that the modern human genome undergoes mutation which makes the adenylosuccinate lyase enzyme less stable, leading to a decrease in purine synthesis. This mutation did not occur in Neanderthals, so the scientists believe that it affected metabolism in brain tissues and thereby strongly contributed to modern humans evolving into a separate species. The research was published in the journal eLife.

The predecessors of modern humans split from their closest evolutionary relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, about 600,000 ...