(Press-News.org) The first detailed cross-section of a galaxy broadly similar to the Milky Way, published today, reveals that our galaxy evolved gradually, instead of being the result of a violent mash-up. The finding throws the origin story of our home into doubt.

The galaxy, dubbed UGC 10738, turns out to have distinct 'thick' and 'thin' discs similar to those of the Milky Way. This suggests, contrary to previous theories, that such structures are not the result of a rare long-ago collision with a smaller galaxy. They appear to be the product of more peaceful change.

And that is a game-changer. It means that our spiral galaxy home isn't the product of a freak accident. Instead, it is typical.

The finding was made by a team led by Nicholas Scott and Jesse van de Sande, from Australia's ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D) and the University of Sydney.

"Our observations indicate that the Milky Way's thin and thick discs didn't come about because of a gigantic mash-up, but a sort-of 'default' path of galaxy formation and evolution," said Dr Scott.

"From these results we think galaxies with the Milky Way's particular structures and properties could be described as the 'normal' ones."

This conclusion - published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters- has two profound implications.

"It was thought that the Milky Way's thin and thick discs formed after a rare violent merger, and so probably wouldn't be found in other spiral galaxies," said Dr Scott.

"Our research shows that's probably wrong, and it evolved 'naturally' without catastrophic interventions. This means Milky Way-type galaxies are probably very common.

"It also means we can use existing very detailed observations of the Milky Way as tools to better analyse much more distant galaxies which, for obvious reasons, we can't see as well."

The research shows that UGC 10738, like the Milky Way, has a thick disc consisting mainly of ancient stars - identified by their low ratio of iron to hydrogen and helium. Its thin disc stars are more recent and contain more metal.

(The Sun is a thin disc star and comprises about 1.5% elements heavier than helium. Thick disc stars have three to 10 times less.)

Although such discs have been previously observed in other galaxies, it was impossible to tell whether they hosted the same type of star distribution - and therefore similar origins.

Scott, van de Sande and colleagues solved this problem by using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile to observe UGC 10738, situated 320 million light years away.

The galaxy is angled "edge on", so looking at it offered effectively a cross-section of its structure.

"Using an instrument called the multi-unit spectroscopic explorer, or MUSE, we were able to assess the metal ratios of the stars in its thick and thin discs," explained Dr van de Sande.

"They were pretty much the same as those in the Milky Way - ancient stars in the thick disc, younger stars in the thin one. We're looking at some other galaxies to make sure, but that's pretty strong evidence that the two galaxies evolved in the same way."

Dr Scott said UGC 10738's edge-on orientation meant it was simple to see which type of stars were in each disc.

"It's a bit like telling apart short people from tall people," he said. "It you try to do it from overhead it's impossible, but it if you look from the side it's relatively easy."

Co-author Professor Ken Freeman from the Australian National University said, "This is an important step forward in understanding how disk galaxies assembled long ago. We know a lot about how the Milky Way formed, but there was always the worry that the Milky Way is not a typical spiral galaxy. Now we can see that the Milky Way's formation is fairly typical of how other disk galaxies were assembled".

ASTRO 3D director, Professor Lisa Kewley, added: "This work shows how the Milky Way fits into the much bigger puzzle of how spiral galaxies formed across 13 billion years of cosmic time."

Other co-authors are based at Macquarie University in Australia and Germany's Max-Planck-Institut fur Extraterrestrische Physik.

INFORMATION:

SPOKANE, Wash.-- Breast cancer screening took a sizeable hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests new research that showed that the number of screening mammograms completed in a large group of women living in Washington State plummeted by nearly half. Published today in JAMA Network Open, the study found the steepest drop-offs among women of color and those living in rural communities.

"Detecting breast cancer at an early stage dramatically increases the chances that treatment will be successful," said lead study author Ofer Amram, an assistant professor in the Washington ...

What The Study Did: Researchers used clinical data to examine differences in breast cancer screenings before and during the COVID-19 pandemic overall and among sociodemographic groups. Data included completed screening mammograms within a large statewide nonprofit community health care system from April 2018 through December 2020.

Authors: Ofer Amram, Ph.D., of Washington State University in Spokane, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10946)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

What The Study Did: This follow-up study of a randomized clinical trial examines the association between survival and C-reactive protein levels in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who were treated with tocilizumab.

Authors: Xavier Mariette, M.D., Ph.D., of the Hôpital Bicêtre in Bicêtre, France, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2209)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined changes in reports to poison control centers from 2017 to 2019 of exposures to manufactured cannabis products and plant materials.

Authors: Julia A. Dilley, Ph.D., of the Oregon Public Health Division in Portland, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10925)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

Tendons are what connect muscles to bones. They are relatively thin but have to withstand enormous forces. Tendons need a certain elasticity to absorb high loads, such as mechanical shock, without tearing. In sports involving sprinting and jumping, however, stiff tendons are an advantage because they transmit the forces that unfold in the muscles more directly to the bones. Appropriate training helps to achieve an optimal stiffening of the tendons.

Researchers from ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich, working at Balgrist University Hospital in Zurich, have now deciphered how the cells of the tendons perceive mechanical ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. - Newborns who experience seizures after birth are at risk of developing long term chronic conditions, such as developmental delays, cerebral palsy or epilepsy.

Which is why all of these babies receive medication to treat the electrical brain disturbances right away.

While some babies only receive antiseizure medicine for a few days at the hospital, others are sent home with antiseizure medicine for months longer out of concern that seizures may reoccur.

But according to a new multicenter study, continuing this treatment after the neonatal seizures stop may not be necessary.

Babies who stayed on antiseizure medications after going home weren't any less likely to develop epilepsy or to have developmental delays than those ...

A new study by University of Liverpool ecologists warns that heat-induced male infertility will see some species succumb to the effects of climate change earlier than thought.

Currently, scientists are trying to predict where species will be lost due to climate change so they can plan effective conservation strategies. However, research on temperature tolerance has generally focused on the temperatures that are lethal to organisms, rather than the temperatures at which organisms can no longer breed.

Published in Nature Climate Change, the study of 43 fruit fly (Drosophila) species showed that in almost half of the species, males became sterile at lower than lethal temperatures. Importantly, the worldwide distribution ...

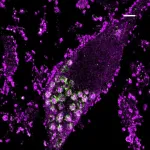

When a single gene in a cell is turned on or off, its resulting presence or absence can affect the function and survival of the cell. In a new study appearing May 24 in Nature Neuroscience, UCSF researchers have successfully catalogued this effect in the human neuron by separately toggling each of the 20,000 genes in the human genome.

In doing so, they've created a technique that can be employed for many different cell types, as well as a database where other researchers using the new technique can contribute similar knowledge, creating a picture of gene function in disease across the entire spectrum of human cells.

"This is the key next step in uncovering the mechanisms behind disease genes," said Martin Kampmann, PhD, associate professor, Institute ...

New research from Florida State University shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said FSU postdoctoral fellow Jon Hawkings. "And that's leading us to look now at a whole host of other questions such as how that mercury could potentially get into the food chain."

The study was published today in Nature Geoscience.

Initially, researchers sampled waters from three different ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- New research shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said Jon Hawkings, a postdoctoral researcher at Florida State University and and the German Research Centre for Geosciences. ...