(Press-News.org) Regular physical activity has positive effects on children's developing brain circuits, finds a Boston Children's Hospital study using neuroimaging data from nearly 6,000 early adolescents. Physical activity of any kind was associated with more efficiently organized, flexible, and robust brain networks, the researchers found. The more physical activity, the more "fit" the brain.

Findings were published in Cerebral Cortex on May 14.

"It didn't matter what kind of physical activity children were involved in - it only mattered that they were active," says Caterina Stamoulis, PhD, principal investigator on the study and director of the Computational Neuroscience Laboratory at Boston Children's. "Being active multiple times per week for at least 60 minutes had a widespread positive effect on brain circuitry."

Specifically, Stamoulis and her trainees, Skylar Brooks and Sean Parks, found positive effects on circuits in multiple brain areas. These circuits play a fundamental role in cognitive function and support attention, sensory processing, motor function, memory, decision-making, and executive control. Regular physical activity also partially offset the effects of unhealthy body mass index (BMI), which was associated with detrimental effects on the same brain circuitry.

Harnessing big data

With support from the National Science Foundation's Harnessing the Data Revolution and BRAIN Initiative, the researchers tapped data from the long-term, NIH-sponsored Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. They analyzed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from 5,955 9- and 10-year-olds and crunched these data against data on physical activity and BMI, using advanced computational techniques developed in collaboration with the Harvard Medical School High Performance Computing Cluster.

"Early adolescence is a very important time in brain development," notes Stamoulis. "It's associated with a lot of changes in the brain's functional circuits, particularly those supporting higher-level processes like decision-making and executive control. Abnormal changes in these areas can lead to risk behaviors and deficits in cognitive function that can follow people throughout their lifetime."

Gauging functional brain organization

The functional MRI data were captured in the resting state, when the children were not performing any explicit cognitive task. This allows analysis of the "connectome" -- the architecture of brain connections that determines how efficiently the brain functions and how readily it can adapt to changes in the environment, independently of specific tasks.

The team adjusted the data for age, gestational age at birth, puberty status, sex, race, and family income. Physical activity and sports involvement measures were based on youth and parent surveys collected by the ABCD study.

The analysis found that physical activity was associated with positive brain-wide network properties reflecting the connectome's efficiency, robustness, and clustering into communities of brain regions. These same properties were detrimentally affected by high BMI. Physical activity also had a positive effect on local organization of the brain; unhealthy BMI had adverse impacts in some of the same areas.

"Based on our results, we think physical activity affects brain organization directly, but also indirectly by reducing BMI, therefore mitigating its negative effects," Stamoulis says.

Optimal functional brain structure consists of small regions or "nodes" that are well connected internally and send information to other parts of the brain through strong, but relatively few, long-range connections, Stamoulis explains.

"This organization optimizes the efficiency of information processing and transmission, which is still developing in adolescence and can be altered by a number of risk factors," she says. "Our results suggest that physical activity has a protective effect on this optimization process across brain regions."

INFORMATION:

Skylar Brooks was first author on the paper. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation (grant nos. 1940094 and 1649865).

About Boston Children's Hospital

Boston Children's Hospital is ranked the #1 children's hospital in the nation by U.S. News & World Report and is the primary pediatric teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School. Home to the world's largest research enterprise based at a pediatric medical center, its discoveries have benefited both children and adults since 1869. Today, 3,000 researchers and scientific staff, including 9 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 23 members of the National Academy of Medicine and 12 Howard Hughes Medical Investigators comprise Boston Children's research community. Founded as a 20-bed hospital for children, Boston Children's is now a 415-bed comprehensive center for pediatric and adolescent health care. For more, visit our Answers blog and follow us on social media @BostonChildrens, @BCH_Innovation, Facebook and YouTube.

The first detailed cross-section of a galaxy broadly similar to the Milky Way, published today, reveals that our galaxy evolved gradually, instead of being the result of a violent mash-up. The finding throws the origin story of our home into doubt.

The galaxy, dubbed UGC 10738, turns out to have distinct 'thick' and 'thin' discs similar to those of the Milky Way. This suggests, contrary to previous theories, that such structures are not the result of a rare long-ago collision with a smaller galaxy. They appear to be the product of more peaceful change.

And that is a game-changer. It means that our spiral galaxy home isn't the product of a freak accident. Instead, it ...

SPOKANE, Wash.-- Breast cancer screening took a sizeable hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests new research that showed that the number of screening mammograms completed in a large group of women living in Washington State plummeted by nearly half. Published today in JAMA Network Open, the study found the steepest drop-offs among women of color and those living in rural communities.

"Detecting breast cancer at an early stage dramatically increases the chances that treatment will be successful," said lead study author Ofer Amram, an assistant professor in the Washington ...

What The Study Did: Researchers used clinical data to examine differences in breast cancer screenings before and during the COVID-19 pandemic overall and among sociodemographic groups. Data included completed screening mammograms within a large statewide nonprofit community health care system from April 2018 through December 2020.

Authors: Ofer Amram, Ph.D., of Washington State University in Spokane, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10946)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

What The Study Did: This follow-up study of a randomized clinical trial examines the association between survival and C-reactive protein levels in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who were treated with tocilizumab.

Authors: Xavier Mariette, M.D., Ph.D., of the Hôpital Bicêtre in Bicêtre, France, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2209)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined changes in reports to poison control centers from 2017 to 2019 of exposures to manufactured cannabis products and plant materials.

Authors: Julia A. Dilley, Ph.D., of the Oregon Public Health Division in Portland, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10925)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

Tendons are what connect muscles to bones. They are relatively thin but have to withstand enormous forces. Tendons need a certain elasticity to absorb high loads, such as mechanical shock, without tearing. In sports involving sprinting and jumping, however, stiff tendons are an advantage because they transmit the forces that unfold in the muscles more directly to the bones. Appropriate training helps to achieve an optimal stiffening of the tendons.

Researchers from ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich, working at Balgrist University Hospital in Zurich, have now deciphered how the cells of the tendons perceive mechanical ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. - Newborns who experience seizures after birth are at risk of developing long term chronic conditions, such as developmental delays, cerebral palsy or epilepsy.

Which is why all of these babies receive medication to treat the electrical brain disturbances right away.

While some babies only receive antiseizure medicine for a few days at the hospital, others are sent home with antiseizure medicine for months longer out of concern that seizures may reoccur.

But according to a new multicenter study, continuing this treatment after the neonatal seizures stop may not be necessary.

Babies who stayed on antiseizure medications after going home weren't any less likely to develop epilepsy or to have developmental delays than those ...

A new study by University of Liverpool ecologists warns that heat-induced male infertility will see some species succumb to the effects of climate change earlier than thought.

Currently, scientists are trying to predict where species will be lost due to climate change so they can plan effective conservation strategies. However, research on temperature tolerance has generally focused on the temperatures that are lethal to organisms, rather than the temperatures at which organisms can no longer breed.

Published in Nature Climate Change, the study of 43 fruit fly (Drosophila) species showed that in almost half of the species, males became sterile at lower than lethal temperatures. Importantly, the worldwide distribution ...

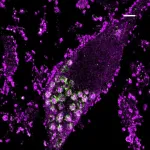

When a single gene in a cell is turned on or off, its resulting presence or absence can affect the function and survival of the cell. In a new study appearing May 24 in Nature Neuroscience, UCSF researchers have successfully catalogued this effect in the human neuron by separately toggling each of the 20,000 genes in the human genome.

In doing so, they've created a technique that can be employed for many different cell types, as well as a database where other researchers using the new technique can contribute similar knowledge, creating a picture of gene function in disease across the entire spectrum of human cells.

"This is the key next step in uncovering the mechanisms behind disease genes," said Martin Kampmann, PhD, associate professor, Institute ...

New research from Florida State University shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said FSU postdoctoral fellow Jon Hawkings. "And that's leading us to look now at a whole host of other questions such as how that mercury could potentially get into the food chain."

The study was published today in Nature Geoscience.

Initially, researchers sampled waters from three different ...