(Press-News.org) BOSTON - In a surprising discovery, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) identified a mechanism that protects the brain from the effects of hypoxia, a potentially lethal deprivation of oxygen. This serendipitous finding, which they report in Nature Communications, could aid in the development of therapies for strokes, as well as brain injury that can result from cardiac arrest, among other conditions.

However, this study began with a very different objective, explains senior author Fumito Ichinose, MD, PhD, an attending physician in the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine at MGH, and principal investigator in the Anesthesia Center for Critical Care Research. One area of focus for Ichinose and his team is developing techniques for inducing suspended animation, that is, putting a human's vital functions on temporary hold, with the ability to "reawaken" them later. This state of being would be similar to what bears and other animals experience during hibernation. Ichinose believes that the ability to safely induce suspended animation could have valuable medical applications, such as pausing the life processes of a patient with an incurable disease until an effective therapy is found. It could also allow humans to travel long distances in space (which has frequently been depicted in science fiction).

A 2005 study found that inhaling a gas called hydrogen sulfide caused mice to enter a state of suspended animation. Hydrogen sulfide, which has the odor of rotten eggs, is sometimes called "sewer gas." Oxygen deprivation in a mammal's brain leads to increased production of hydrogen sulfide. As this gas accumulates in the tissue, hydrogen sulfide can halt energy metabolism in neurons and cause them to die. Oxygen deprivation is a hallmark of ischemic stroke, the most common type of stroke, and other injuries to the brain.

In the Nature Communications study, Ichinose and his team initially set out to learn what happens when mice are exposed to hydrogen sulfide repeatedly, over an extended period. At first, the mice entered a suspended-animation-like state--their body temperatures dropped and they were immobile. "But, to our surprise, the mice very quickly became tolerant to the effects of inhaling hydrogen sulfide," says Ichinose. "By the fifth day, they acted normally and were no longer affected by hydrogen sulfide."

Interestingly, the mice that became tolerant to hydrogen sulfide were also able to tolerate severe hypoxia. What protected these mice from hypoxia? Ichinose's group suspected that enzymes in the brain that metabolize sulfide might be responsible. They found that levels of one enzyme, called sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase (SQOR), rose in the brains of mice when they breathed hydrogen sulfide several days in a row. They hypothesized that SQOR plays a part in resistance to hypoxia.

There was strong evidence for this hypothesis in nature. For example, female mammals are known to be more resistant than males to the effects of hypoxia--and the former have higher levels of SQOR. When SQOR levels are artificially reduced in females, they become more vulnerable to hypoxia. (Estrogen may be responsible for the observed increase in SQOR, since protection from the adverse effects of hypoxia is lost when a female mammal's estrogen-producing ovaries are removed.) Moreover, some hibernating animals, such as the thirteen-lined ground squirrel, are highly tolerant of hypoxia, which allows them to survive as their bodies' metabolism slows down during the winter. A typical ground squirrel's brain has 100 times more SQOR than that of a similar-sized rat. However, when Ichinose and colleagues "turned off" expression of SQOR in the squirrels' brains, their protection against the effects of hypoxia vanished.

Meanwhile, when Ichinose and colleagues artificially increased SQOR levels in the brains of mice, "they developed a robust defense against hypoxia," explains Ichinose. His team increased the level of SQOR using gene therapy, an approach that is technically complex and not practical at this point. On the other hand, Ichinose and his colleagues demonstrated that "scavenging" sulfide, by using an experiment drug called SS-20, reduced levels of the gas, thereby sparing the brains of mice when they were deprived of oxygen.

Human brains have very low levels of SQOR, meaning that even a modest accumulation of hydrogen sulfide can be harmful, says Ichinose. "We hope that someday we'll have drugs that could work like SQOR in the body," he says, noting that his lab is studying SS-20 and several other candidates. Such medications could be used to treat ischemic strokes, as well as patients who have suffered cardiac arrest, which can lead to hypoxia. Ichinose's lab is also investigating how hydrogen sulfide affects other parts of the body. For example, hydrogen sulfide is known to accumulate in other conditions, such as certain types of Leigh syndrome, a rare but severe neurological disorder that usually leads to early death. "For some patients," says Ichinose, "treatment with a sulfide scavenger might be lifesaving."

INFORMATION:

The lead author of the study is Eizo Marutani, MD, an investigator in MGH's Department of Anesthesia Critical Care and Pain Medicine and an instructor at Harvard Medical School (HMS). Ichinose is also the William Thomas Green Morton Professor of Anaesthesia at HMS.

This study was funded by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Sciences, Sports, and Technology; the Japan Science and Technology Agency; the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute of General Medical Science; and the National Science Foundation.

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2020, Mass General was named #6 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

Bottom Line: In a new recommendation statement, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that clinicians offer pregnant adolescents and adults effective behavioral counseling interventions aimed at promoting healthy weight gain and preventing excess gestational weight gain in pregnancy. Excess weight at the beginning of pregnancy and excess gestational weight gain have been associated with adverse maternal and infant health outcomes such as a large for gestational age infant, cesarean delivery or preterm birth. The USPSTF routinely makes recommendations about the effectiveness of preventive care ...

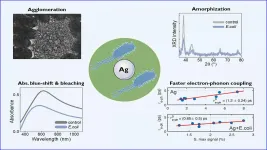

WASHINGTON, May 25, 2021 -- For millennia, silver has been utilized for its antimicrobial and antibacterial properties. Although its use as a disinfectant is widely known, the effects of silver's interaction with bacteria on the silver itself are not well understood.

As antibiotic-resistant bacteria become more and more prevalent, silver has seen steep growth in its use in things like antibacterial coatings. Still, the complex chain of events that lead to the eradication of bacteria is largely taken for granted, and a better understanding of this process can provide clues on how to best apply it.

In Chemical Physics Reviews, by AIP Publishing, researchers from Italy, the United States, and Singapore studied the impacts an interaction with bacteria has on silver's ...

What The Study Did: This study evaluates the association between bitter taste receptor types (supertasters who experience greater intensity of bitter tastes; tasters; and nontasters who experience low intensity of bitter tastes or no bitter tastes) and outcomes after infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Authors: Henry P. Barham, MD, Sinus and Nasal Specialists of Louisiana in Baton Rouge, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11410)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined if circulating sex hormones are associated with disease severity in patients with COVID-19.

Authors: Sandeep Dhindsa, M.D., of the St Louis University School of Medicine and Abhinav Diwan, M.D., of the Washington University School of Medicine, both in St. Louis, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11398)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, ...

What The Study Did: Rates of depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts and posttraumatic stress disorder among current and former coal miners in the United States were examined in this study.

Authors: Drew Harris, M.D., of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11110)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and ...

Throughout the pandemic, doctors have seen evidence that men with COVID-19 fare worse, on average, than women with the infection. One theory is that hormonal differences between men and women may make men more susceptible to severe disease. And since men have much more testosterone than women, some scientists have speculated that high levels of testosterone may be to blame.

But a new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that, among men, the opposite may be true: that low testosterone levels in the blood are linked to more severe disease. The study could not prove ...

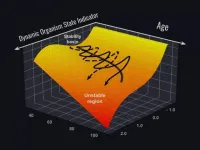

The research team of Gero, a Singapore-based biotech company in collaboration with Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo NY, announces a publication in Nature Communications, a journal of Nature portfolio, presenting the results of the study on associations between aging and the loss of the ability to recover from stresses.

Recently, we have witnessed the first promising examples of biological age reversal by experimental interventions. Indeed, many biological clock types properly predict more years of life for those who choose healthy lifestyles or quit unhealthy ones, such as smoking. What has been still unknown is how quickly biological age is changing over time for the same individual. And especially, how one would distinguish between the ...

An international and multidisciplinary team led by researchers at the University of Oxford, University of Glasgow, and University of Heidelberg, has uncovered the interactions that SARS-CoV-2 RNA establishes with the host cell, many of which are fundamental for infection. These discoveries pave the way for the development of new therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 with broad-range antiviral potential.

The genetic information of SARS-CoV-2 is encoded in an RNA molecule instead DNA. This RNA must be multiplied, translated, and packaged into new viral particles to produce the viral progeny. Despite the complexity of these processes, SARS-CoV-2 only encodes a handful ...

Swedish and Danish journalists describe their role as monitorial to a greater extent than journalists from other Nordic countries. Journalists from Norway and Iceland state they have the least experience of political influence and thus differ from Finnish journalists. This is shown by a new comparative study published by Nordicom at the University of Gothenburg.

In a new study, researchers examine the similarities and differences in Nordic journalists' perceptions of the role of journalists and different kinds of influence on journalistic work. They also compare the Nordic perceptions with journalists in the rest of Europe. The study is ...

With a global impetus toward utilizing more renewable energy sources, wind presents a promising, increasingly tapped resource. Despite the many technological advancements made in upgrading wind-powered systems, a systematic and reliable way to assess competing technologies has been a challenge.

In a new case study, researchers at Texas A&M University, in collaboration with international energy industry partners, have used advanced data science methods and ideas from the social sciences to compare the performance of different wind turbine designs.

"Currently, there is no method to validate if a newly created technology will increase wind energy production and efficiency by a certain amount," said Dr. Yu Ding, ...