(Press-News.org) Mercury pollution is an issue of global concern due to its toxic effects. High levels have already been measured in Arctic organisms - with worrying effects on ecosystems and the food chain. So far, the Greenland Ice Sheet has not been taken into account as a part of the Arctic mercury cycle. Now, researchers led by Jon Hawkings of the German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam and Florida State University show that meltwaters in the southwest of Greenland transport considerable amounts of mercury into the Arctic Ocean. Due to the large quantities detected, the researchers assume that they are of geological origin. They present their measurements in the current issue of Nature Geoscience.

Mercury: poison for humans and the environment - especially in the Arctic

Mercury is hardly useful biologically, but proves to be all the more toxic in the form of various chemical compounds. It accumulates in the food chain and becomes a danger to humans through the consumption of fish and seafood. The socio-economic costs associated with the environmental and health impacts are estimated at more than five billion US dollars per year.

A significant aggravation of this problem is due to fossil energy production, industry, mining and transport. But there are also natural sources such as emissions from volcanoes, fire and the weathering of mercury-containing rocks. The Arctic is proving to be a particular problem zone in both respects: the mercury content in marine organisms there has increased by an order of magnitude over the past 150 years. Dust particles and aerosols enter this region via the atmosphere, and climate change and the associated warming of the Arctic lead to higher inputs through more and stronger meltwaters.

International team focuses on Greenland ice sheet

The Greenland Ice Sheet, which covers about a quarter of the Arctic land mass, has received little attention in this context so far. This has been changed by a 22-member international research team led by Jon Hawkings, postdoctoral researcher in the Interfacial Geochemistry Section at GFZ and Florida State University, with 17 participating institutions from Europe and the USA (see below). In measurement campaigns during the Arctic summers of 2012, 2015 and 2018, they took samples from three meltwater outflows from glacier catchments on the southwestern edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet and downstream fjords. The meltwater was filtered in the laboratory tent, the filtered sediment air-dried, cooled and subjected to initial analyses. Mercury levels were determined in detail in the laboratories of the participating institutions, among other things with mass and fluorescence spectrometry.

Surprisingly high mercury concentrations

Originally, Hawkings and his colleague, glaciologist Jemma Wadham, professor at the Cabot Institute for the Environment at the University of Bristol, wanted to investigate the content and pathways of nutrients in these waters. During the analysis, they were then surprised by extremely high mercury levels, comparable to rivers in industrial China: the typical level of dissolved mercury in rivers is around 1 to 10 nanograms per litre. This is equivalent to a grain-of-salt-sized amount of mercury in an Olympic-sized swimming pool of water. However, in the meltwater rivers of Greenland's glaciers, the researchers found much higher levels of more than 150 nanograms per litre. Undissolved mercury particles were found in even much higher concentrations of more than 2000 nanograms per litre.

"The export of dissolved mercury from this region must be considered globally significant," Jon Hawkings emphasises. He says it is up to 42 tons per year, which is about ten per cent of the estimated global riverine export of mercury to the oceans. "This is among the highest concentrations of dissolved mercury ever measured in natural waters. And environmentally high levels persist in downstream fjords, posing a potential risk of accumulation in coastal food webs," Hawkings said.

Climate change is likely to further aggravate the situation

This finding is particularly relevant not least against the background that fishing is Greenland's primary industry with the country being a major exporter of cold-water shrimp, halibut and cod.

"We've learned from many years of fieldwork at these sites in Western Greenland that glaciers export nutrients to the ocean, but the discovery that they may also carry potential toxins unveils a concerning dimension to how glaciers influence water quality and downstream communities, which may alter in a warming world and highlights the need for further investigation," Jemma Wadham said.

Natural source requires rethinking of conservation measures

The source of the large amounts of mercury detected is very likely the Earth itself, at the base of the ice sheet, Hawkings believes. This is suggested, among other things, by comparative data from the surface of snow and ice, where it accumulates from burning fossil fuels or another industrial source. That could be important for scientists and policymakers to plan for managing mercury pollution in the future.

"All the efforts to manage mercury thus far have come from the idea that the increasing concentrations we have been seeing across the Earth system come primarily from direct anthropogenic activity, like industry," Hawkings said. "But mercury coming from climatically sensitive environments like glaciers could be a source that is much more difficult to manage."

INFORMATION:

Researchers from the following institutions contributed to the study:

USA (USGS, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, University of California Santa Cruz, Brigham Young University), UK (University of Bristol, University of Glasgow), Czech Republic (Charles University), Norway (UiT The Arctic University of Norway, UiO University of Oslo), Greenland (Greenland Climate Research Centre), Netherlands (Royal Netherlands Institute of Sea Research).

**Funding: Jon Hawkings is a post-doctoral fellow at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences. As part of his Horizon 2020 MSCA Marie Sk?odowska Curie Actions Global Fellowship, he has been working at Florida State University FSU (USA) for two years starting in 2018, before now continuing his research in Potsdam. His project is entitled "ICICLES - Iron and Carbon Interactions and Biogeochemical CycLing in Subglacial EcosystemS".

Original study: Hawkings, J.R., Linhoff, B.S., Wadham, J.L. et al. Large subglacial source of mercury from the southwestern margin of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Nat. Geosci. (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-021-00753-w

Media contact:

Dr. Uta Deffke

Public and Media Relations

Helmholtz Centre Potsdam

GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences

Telegrafenberg

14473 Potsdam

Phone: +49 331 288-1049

Email: uta.deffke@gfz-potsdam.de

LAWRENCE -- For two weeks in June 2020, a massive dust plume from Saharan Africa crept westward across the Atlantic, blanketing the Caribbean and Gulf Coast states in the U.S. The dust storm was so strong, it earned the nickname "Godzilla."

Now, researchers from the University of Kansas have published a new study in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society parsing the mechanism that transported the dust. Their results explain a phenomenon that could occur more frequently in the years ahead due to climate change, affecting human health and transportation systems.

African dust darkened the skies of the Caribbean and American Gulf States thanks to a trio of atmospheric patterns, ...

Mitochondria are the cell's power plants and produce the majority of a cell's energy needs through an electrochemical process called electron transport chain coupled to another process known as oxidative phosphorylation. A number of different proteins in mitochondria facilitate these processes, but it's not fully understood how these proteins are arranged inside mitochondria and the factors that can influence their arrangement.

Now, scientists at the University of Copenhagen have used state-of-the-art proteomics technology to shine new light on how mitochondrial proteins gather into electron transport chain complexes, and further into so-called supercomplexes. The research, which is published in Cell Reports, also examined ...

Over the years, robots have gotten quite good at identifying objects -- as long as they're out in the open.

Discerning buried items in granular material like sand is a taller order. To do that, a robot would need fingers that were slender enough to penetrate the sand, mobile enough to wriggle free when sand grains jam, and sensitive enough to feel the detailed shape of the buried object.

MIT researchers have now designed a sharp-tipped robot finger equipped with tactile sensing to meet the challenge of identifying buried objects. In experiments, the aptly named ...

A mathematical model which can predict landslides that occur unexpectantly has been developed by two University of Melbourne scientists, with colleagues from GroundProbe-Orica and the University of Florence.

Professors Antoinette Tordesillas and Robin Batterham led the work over five years to develop and test the model SSSAFE (Spatiotemporal Slope Stability Analytics for Failure Estimation), which analyses slope stability over time to predict where and when a landslide or avalanche is likely to occur.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, the research team was ...

Discovered by Victor Hess in 1912, cosmic rays, relativisitic particles that shower Earth, contribute a signicant part of the energy density in the universe and carries unambiguous informations on various astrophysical processes . Yet until now, origin of cosmic rays is still a mystery.

A key problem in understanding the origin of cosmic rays is the searching for the acceleration site up to or even beyond Ultra-high energy (UHE). Such extreme accelerators are dubbed as PeVatrons. However, composed of subatomic particles, such as protons or atomic nuclei, cosmic rays are charged and lose ...

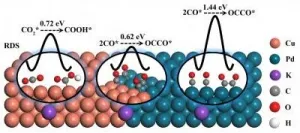

Using intermittent electric energy to convert excessive CO2 into C2 products, such as ethylene and ethanol, is an effective strategy to mitigate the greenhouse effect. Copper (Cu) is the only single metal catalyst which can converts CO2 into C2 products by electrochemical method, but with undesirable selectivity of C2 product. Therefore, how to improve the conversion efficiency of Cu-based catalysts for reducing CO2 to C2 product has attracted great attention.

Recently, a research team led by Prof. Min Liu from Central South University, China designed a Cu-Pd bimetallic electrocatalyst possessing CuPd(100) interface which can lower the energy barrier of C2 product generation. The electrocatalyst was obtained through using ...

WASHINGTON--People who eat too many refined carbs and fatty meats for dinner have a higher risk of heart disease than those who eat a similar diet for breakfast, according to a nationwide study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Cardiovascular diseases like congestive heart failure, heart attack and stroke are the number one cause of death globally, taking an estimated 17.9 million lives each year. Eating lots of saturated fat, processed meats and added sugars can raise your cholesterol and increase your risk of heart disease. Eating a heart-healthy diet with more whole carbohydrates like vegetables and grains and less meat can significantly offset the risk of cardiovascular disease.

"Meal timing along with food quality are important factors ...

The farming of livestock to feed the global appetite for animal products greatly contributes to global warming. A new study however shows that emission intensity per unit of animal protein produced from the sector has decreased globally over the past two decades due to greater production efficiency, raising questions around the extent to which methane emissions will change in the future and how we can better manage their negative impacts.

Despite what we know about the environmental cost of livestock production, the global appetite for animal products such as meat, eggs, and dairy continues to grow. The livestock sector is in fact the largest source of manmade methane emissions globally, and these emissions are projected ...

A team of international researchers has found that the Tsimane indigenous people of the Bolivian Amazon experience less brain atrophy than their American and European peers. The decrease in their brain volumes with age is 70% slower than in Western populations. Accelerated brain volume loss can be a sign of dementia.

The study was published May 26, 2021 in the Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences.

Although people in industrialized nations have access to modern medical care, they are more sedentary and eat a diet high in saturated fats. In contrast, the Tsimane ...

UC San Francisco researchers have found a way to double doctors' accuracy in detecting the vast majority of complex fetal heart defects in utero - when interventions could either correct them or greatly improve a child's chance of survival - by combining routine ultrasound imaging with machine-learning computer tools.

The team, led by UCSF cardiologist Rima Arnaout, MD, trained a group of machine-learning models to mimic the tasks that clinicians follow in diagnosing complex congenital heart disease (CHD). Worldwide, humans detect as few as 30 to 50 percent of these conditions before birth. However, the combination of human-performed ultrasound ...