Study identifies risk for some childhood cancer patients developing secondary leukaemia

New study used whole genome sequencing to gain further understanding of why some children develop secondary leukaemia after neuroblastoma treatment

2021-05-28

(Press-News.org) Scientists from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Cambridge found that in children with neuroblastoma - a cancer of immature nerve cells - treatment with platinum chemotherapy caused changes to the genome that could then cause leukaemia in some children later on.

The findings, published 27th May 2021 in Blood could lead to an ability to identify which children are more likely to develop the secondary cancer. This in turn could lead to changes in their treatment plan to either avoid these risks or take measures to prepare.

Secondary blood cancer is a challenging complication of childhood neuroblastoma cancer treatment. Every year around 100 children in the UK are diagnosed with neuroblastoma*, and those who had high-risk treatment are at an increased risk of developing secondary blood cancer - leukaemia - after neuroblastoma treatment.

Neuroblastoma often requires intense treatment including several chemotherapy drugs. These powerful drugs kill cancer cells very effectively but unfortunately also have side effects, including damaging the DNA of healthy cells, including bone marrow cells. In up to 7 per cent of childhood neuroblastoma survivors, damaged bone marrow cells go on to develop into secondary leukaemia.

In this new study, researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Cambridge sequenced the whole genomes of bone marrow and blood samples of two children who both had developed blood cancer following high-risk neuroblastoma treatment. They discovered that the seeds of secondary leukaemia were sown by neuroblastoma chemotherapy right at the beginning of treatment.

Dr Sam Behjati, co-lead author and group leader at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: "We have been able to unravel the root of secondary leukaemia in these children which seems to lie in the early stages of neuroblastoma treatment. We hope to further investigate this to try to identify children at higher risk, and to inform a more tailored treatment plan to reduce the risk of secondary leukaemia."

The team found that in both patients the leukaemia had mutations that were caused by neuroblastoma chemotherapy. A wider analysis of 17 children treated for a variety of cancers then identified another child who had undergone neuroblastoma treatment and had developed pre-leukaemia seeds. In the future, it could be possible to identify the children who have a higher risk of developing secondary leukaemia by sequencing their genome and highlighting any genetic drivers that could be pre-cursors for blood cancer.

Dr Grace Collord, joint first author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: "This research would not have been possible without the contributions of the patients and their families, and we are indebted to them for their participation in this study. Understanding the reason why some childhood cancer survivors go on to develop secondary blood cancer is crucial if we are to find a way to help protect against this devastating complication."

Professor John Anderson of Great Ormond Street Hospital, who contributed to this study, said: "Neuroblastoma can be an aggressive disease that requires intense chemotherapy treatment. Occasionally this chemotherapy can cause serious adverse effects such as leukaemia. So these findings are important to inform possible strategies for monitoring for secondary cancer and tailoring individual treatment plans. However, I should stress that it remains vital that children with high risk neuroblastoma continue to receive intense treatment for their cancer."

INFORMATION:

This study included patients, research nursing teams, and laboratory staff from Addenbrooke's Cambridge University Hospital and Great Ormond Street Hospital (London).

*Children with Cancer UK. Neuroblastoma overview, accessed 02/03/2021. Available at: https://www.childrenwithcancer.org.uk/childhood-cancer-info/cancer-types/neuroblastoma/#:~:text=are%20not%20known.-,Incidence,the%20age%20of%2010%20years.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-28

The group of experts includes Professor and Academician of Tallinn University of Technology Jarek Kurnitski, who said that improving ventilation can be regarded more broadly as a paradigm shift equal in scale to the transformation in the standards of drinking water supplies and food hygiene. "There has long been no doubt that you can get infection when you drink water or eat food that has been contaminated. Now we must work towards providing clean air so we can breathe safely," Kurnitski said.

He added, "Researchers see updating of ventilation standards, ventilation requirements based on the probability of infection and more efficient and flexible ventilation systems as a solution. High air change rates are required only in the event of an epidemic, at any ...

2021-05-28

Varying immune response to vaccinations could be countered with microbiota-targeted interventions helping infants, older people and others to take full advantage of the benefits of effective vaccines, Australian and US experts say.

A comprehensive review in Nature Reviews Immunology concludes that evidence is mounting in clinical trials and other studies that the composition and function of individuals' gut microbiota are "crucial factors" in affecting immune responses to vaccinations.

"Never before has the need been greater for robust and long-lasting immunity from our vaccination programs, particularly in low and middle-income countries, and for populations at increased ...

2021-05-28

Researchers at the University of Adelaide are concerned video sharing platforms such as YouTube could be contributing to the normalisation of exotic pets and encouraging the exotic pet trade.

In a study, published in PLOS ONE, researchers analysed the reactions of people to videos on YouTube involving human interactions with exotic animals and found those reactions to be overwhelmingly positive.

The researchers analysed the reactions - via text and emoji usage - in comments posted on 346 popular videos starring exotic wild cats and primates in 'free handling situations'.

These situations involved exotic animals interacting with humans or other animals, such as domestic cats and dogs. The videos examined received ...

2021-05-28

Public use of parks and reserves increased only slightly during last year's COVID-19 national lockdown despite gyms and sports facilities shutting down, a University of Queensland study found.

UQ School of Biological Sciences PhD candidate Violeta Berdejo-Espinola surveyed 1000 people in Brisbane, measuring their use of urban green space and the benefits people associated with visiting the areas during lockdown.

"People all around Brisbane, myself included, noticed a boom in park use in 2020, but while more people ventured into local parks, many folks were left indoors," Ms Berdejo-Espinola said.

"Thirty-six ...

2021-05-28

Professor YAO Huajian's research group from the School of Earth and Space Sciences of the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), in cooperation with Dr. Piero Poli from Grenoble-Alpes University of France, combined the unique resolution reflected body waves (P410P and P660P) retrieved from ambient noise interferometry with mineral physics modeling, to shed new light on transition zone physics. Relevant work was published in Nature Communications.

The subduction of oceanic slabs is an important process of the earth's internal material circulation. Studying the ...

2021-05-28

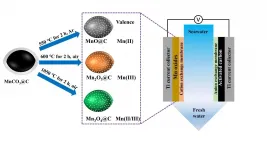

Recently, the researchers from Institute of Solid State Physics, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, by using valence engineering, developed three manganese oxides as electrodes with different Mn valences for high-performance capacitive desalination.

Reverse osmosis and thermal distillation are widely used to treat salt water with high salt concentration, but they have disadvantages including high energy consumption and high cost.

As an alternative method, capacitive deionization (CDI) technology can remove charged ions ...

2021-05-28

University of Virginia School of Medicine researchers have shed new light on how our brains develop, revealing that the very last step in cell division is crucial for the brain to reach its proper size and function.

The new findings identify a potential contributor to microcephaly, a birth defect in which the head is underdeveloped and abnormally small. That's because the head grows as the brain grows. The federal Centers for Disease Control estimates that microcephaly affects from 1 in 800 children to 1 in 5,000 children in the United States each year. The condition is associated with learning disabilities, developmental delays, ...

2021-05-28

Waking up just one hour earlier could reduce a person's risk of major depression by 23%, suggests a sweeping new genetic study published May 26 in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

The study of 840,000 people, by researchers at University of Colorado Boulder and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, represents some of the strongest evidence yet that chronotype--a person's propensity to sleep at a certain time --influences depression risk.

It's also among the first studies to quantify just how much, or little, change is required to influence mental health. ...

2021-05-28

Until now, competing types of robotic hand designs offered a trade-off between strength and durability. One commonly used design, employing a rigid pin joint that mimics the mechanism in human finger joints, can lift heavy payloads, but is easily damaged in collisions, particularly if hit from the side. Meanwhile, fully compliant hands, typically made of molded silicone, are more flexible, harder to break, and better at grasping objects of various shapes, but they fall short on lifting power.

The DGIST research team investigated the idea that a partially-compliant ...

2021-05-28

Australian scientists have found what could prove to be a new and effective way to treat a particularly aggressive blood cancer in children.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, or ALL, is the most common cancer diagnosed in children. Despite dramatic improvements in the survival of children with ALL over past several decades, children who develop 'high risk' ALL - subtypes that grow aggressively and are often resistant to standard treatments - often relapse, and many of these children die from their disease.

One common type of high-risk ALL for which new therapies are urgently needed is 'Philadelphia chromosome-like ALL' (Ph-like ALL), named for its similarity ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study identifies risk for some childhood cancer patients developing secondary leukaemia

New study used whole genome sequencing to gain further understanding of why some children develop secondary leukaemia after neuroblastoma treatment