INFORMATION:

Extreme CO2 greenhouse effect heated up the young Earth

2021-05-31

(Press-News.org) Very high atmospheric CO2 levels can explain the high temperatures on the still young Earth three to four billion years ago. At the time, our Sun shone with only 70 to 80 per cent of its present intensity. Nevertheless, the climate on the young Earth was apparently quite warm because there was hardly any glacial ice. This phenomenon is known as the 'paradox of the young weak Sun.' Without an effective greenhouse gas, the young Earth would have frozen into a lump of ice. Whether CO2, methane, or an entirely different greenhouse gas heated up planet Earth is a matter of debate among scientists. New research by Dr Daniel Herwartz of the University of Cologne, Professor Dr Andreas Pack of the University of Göttingen, and Professor Dr Thorsten Nagel of the University of Aarhus (Denmark) now suggests that high CO2 levels are a plausible explanation. This would also solve another geoscientific problem: ocean temperatures that were apparently too high. The article "A CO2 greenhouse efficiently warmed the early Earth and decreased seawater 18O/16O before the onset of plate tectonics" appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A much-debated question in earth science concerns the temperatures of the early oceans. There is evidence that they were very hot. Measurements of oxygen isotopes on very old limestone or siliceous rocks, which serve as geothermometers, indicate seawater temperatures above 70°C. Lower temperatures would only have been possible if the seawater had changed its oxygen isotope composition. However, this was long considered unlikely.

Models from the new study show that high CO2 levels in the atmosphere may provide an explanation, since they would also have caused a change in the ocean's composition. 'High CO2 levels would thus explain two phenomena at once: first, the warm climate on Earth, and second, why geothermometers appear to show hot seawater. Taking into account the different oxygen isotope ratio of seawater, we would arrive at temperatures closer to 40°C,' said Daniel Herwartz of the University of Cologne. It is conceivable that there was also a lot of methane in the atmosphere. But that would not have had any effect on the composition of the ocean. Thus, it would not explain why the oxygen geothermometer indicates temperatures that are too high. 'Both phenomena can only be explained by high levels of CO2,' Herwartz added. The authors estimate the total amount of CO2 to have totalled approximately one bar. That would be as if today's entire atmosphere consisted of CO2.

'Today, CO2 is just a trace gas in the atmosphere. Compared to that, one bar sounds like an absurdly large amount. However, looking at our sister planet Venus with its approximately 90 bar of CO2 puts things into perspective,' explained Andreas Pack from the University of Göttingen. On Earth, CO2 was eventually removed from the atmosphere and the ocean and stored in the form of coal, oil, gas, and black shales as well as in limestone. These carbon reservoirs are mainly located on the continents. However, the young Earth was largely covered by oceans and there were hardly any continents, so the storage capacity for carbon was limited. 'That also explains the enormous CO2 levels of the young Earth from today's perspective. After all, roughly three billion years ago, plate tectonics and the development of land masses in which carbon could be stored over a long period of time was just picking up speed,' explained Thorsten Nagel from Aarhus University.

For the carbon cycle, the onset of plate tectonics changed everything. Large land masses with mountains provided faster silicate weathering, which converted CO2 into limestone. In addition, carbon became effectively trapped in the Earth's mantle as oceanic plates were subducted. Plate tectonics thus caused the CO2 content of the atmosphere to drop sharply. Repeated ice ages show that it became significantly colder on Earth. 'Earlier studies had already indicated that the limestone contents in ancient basalts point to a sharp drop in atmospheric CO2 levels. This fits well with an increase in oxygen isotopes at the same time. Everything indicates that the atmospheric CO2 content declined rapidly after the onset of plate tectonics,' Daniel Herwartz concluded. However, in this context 'rapidly' refers to several hundred million years.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Duetting songbirds 'mute' the musical mind of their partner to stay in sync

2021-05-31

Art Garfunkel once described his legendary musical chemistry with Paul Simon, "We meet somewhere in the air through the vocal cords ... ." But a new study of duetting songbirds from Ecuador, the plain-tail wren (Pheugopedius euophrys), has offered another tune explaining the mysterious connection between successful performing duos.

It's a link of their minds, and it happens, in fact, as each singer mutes the brain of the other as they coordinate their duets.

In a study published May 31 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers studying brain ...

Researchers report reference genome for maize B chromosome

2021-05-31

Three groups (Dr. James Birchler's group from University of Missouri, Dr. Jan Barto's group from Institute of Experimental Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences and Dr. HAN Fangpu's group from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences) recently reported a reference sequence for the supernumerary B chromosome in maize in a study published online in PNAS (doi:10.1073/pnas.2104254118).

Supernumerary B chromosomes persist in thousands of plant and animal genomes despite being nonessential. They are maintained in populations by mechanisms of "drive" that make them inherited at higher than typical Mendelian rates. Key properties such as its origin, evolution, and the molecular mechanism for its accumulation in ...

Newly discovered African 'climate seesaw' drove human evolution

2021-05-31

While it is widely accepted that climate change drove the evolution of our species in Africa, the exact character of that climate change and its impacts are not well understood. Glacial-interglacial cycles strongly impact patterns of climate change in many parts of the world, and were also assumed to regulate environmental changes in Africa during the critical period of human evolution over the last ~1 million years. The ecosystem changes driven by these glacial cycles are thought to have stimulated the evolution and dispersal of early humans.

A paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) this week challenges this view. Dr. Kaboth-Bahr ...

Using fossil plant molecules to track down the Green Sahara

2021-05-31

The Sahara has not always been covered by only sand and rocks. During the period from 14,500 to 5,000 years ago large areas of North Africa were more heavily populated, and where there is desert today the land was green with vegetation. This is evidenced by various sites with rock paintings showing not only giraffes and crocodiles, but even illustrating people swimming in the "Cave of Swimmers". This period is known as the Green Sahara or African Humid Period. Until now, researchers have assumed that the necessary rain was brought from the tropics through an enhanced summer monsoon. The northward shift of the monsoon was attributed to rotation of the Earth's tilted axis that produces higher levels of ...

Emotional regulation technique may be effective in disrupting compulsive cocaine addiction

2021-05-31

An emotion regulation strategy known as cognitive reappraisal helped reduce the typically heightened and habitual attention to drug-related cues and contexts in cocaine-addicted individuals, a study by Mount Sinai researchers has found. In a paper published in PNAS, the team suggested that this form of habit disruption, mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain, could play an important role in reducing the compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse that are the hallmarks, and long-standing challenges, of addiction.

"Relapse in addiction is often precipitated by heightened attention-bias to drug-related cues, which could consist of sights, smells, ...

Brain activity reveals when white lies are selfish

2021-05-31

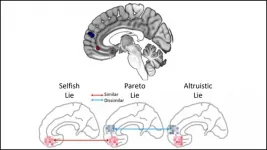

You may think a little white lie about a bad haircut is strictly for your friend's benefit, but your brain activity says otherwise. Distinct activity patterns in the prefrontal cortex reveal when a white lie has selfish motives, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

White lies -- formally called Pareto lies -- can benefit both parties, but their true motives are encoded by the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). This brain region computes the value of different social behaviors, with some subregions focusing on internal motivations and others on external ones. Kim and Kim predicted activity patterns in these subregions could elucidate the true motive behind white lies.

The research team deployed a stand in for white lies, having participants tell lies to earn a reward ...

Ethnic diversity helps identify more genomic regions linked to diabetes-related traits

2021-05-31

By including multi-ethnic participants, a largescale genetic study has identified more regions of the genome linked to type 2 diabetes-related traits than if the research had been conducted in Europeans alone.

The international MAGIC collaboration, made up of more than 400 global academics, conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis led by the University of Exeter. Now published in Nature Genetics, their findings demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields more and better results, as well as ultimately benefitting global patient care.

Up to now, nearly 87 per cent of ...

Medical AI models rely on 'shortcuts' that could lead to misdiagnosis of COVID-19

2021-05-31

Artificial intelligence promises to be a powerful tool for improving the speed and accuracy of medical decision-making to improve patient outcomes. From diagnosing disease, to personalizing treatment, to predicting complications from surgery, AI could become as integral to patient care in the future as imaging and laboratory tests are today.

But as University of Washington researchers discovered, AI models -- like humans -- have a tendency to look for shortcuts. In the case of AI-assisted disease detection, these shortcuts could lead to diagnostic errors if deployed in clinical settings.

In a new paper published May 31 in Nature Machine Intelligence, ...

Isolating an elusive missing link

2021-05-31

The Water Oxidation Reaction (WOR) is one of the most important reactions on the planet since it is the source of nearly all the atmosphere's oxygen. Understanding its intricacies can hold the key to improve the efficiency of the reaction. Unfortunately, the reaction's mechanisms are complex and the intermediates highly unstable, thus making their isolation and characterisation extremely challenging. To overcome this, scientists are using molecular catalysts as models to understand the fundamental aspects of water oxidation - particularly the oxygen-oxygen bond-forming reaction.

For the first time, scientists in ICIQ's ...

Global warming already responsible for one in three heat-related deaths

2021-05-31

Between 1991 and 2018, more than a third of all deaths in which heat played a role were attributable to human-induced global warming, according to a new article in Nature Climate Change.

The study, the largest of its kind, was led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and the University of Bern within the Multi-Country Multi-City (MCC) Collaborative Research Network. Using data from 732 locations in 43 countries around the world it shows for the first time the actual contribution of man-made climate change in increasing mortality risks due to heat.

Overall, ...