INFORMATION:

Prof. Nachum Ulanovsky is the incumbent of the Barbara and Morris L. Levinson Professorial Chair in Brain Research.

Prof. Ulanovsky's research is supported by Dita & Yehuda L. Bronicki; the ERC; and the DFG-SFB.

Right off the bat: Navigation in extra-large spaces

Bats navigating in an innovative extra-large experimental setup reveal an unknown neuronal code

2021-06-01

(Press-News.org) The brain is often likened to a computer: its hardware - neurons organized in complex circuits, its software - a plethora of codes that govern the neurons' behavior. But sometimes the brain performs exceptionally well even when its hardware seems inadequate for the task. For example, it's been puzzling how we and other mammals manage to navigate large-scale environments even though the brain's spatial perception circuits are seemingly suited to representing much smaller areas. A team of researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science, led by Prof. Nachum Ulanovsky of the Neurobiology Department, tackled this riddle by thinking outside the experimental box. By combining an unusual research model - fruit bats - with an unusual setting - a 200 meters-long bat-tunnel - they were successful in revealing a novel neuronal code for spatial perception, as reported today in Science.

"Bats and other mammals navigate very large environments in nature," says Ulanovsky. "In one night a bat can cover an area that is about 20 kilometers long, 2 kilometers wide and half a kilometer high. This is very different from the 1 square meter boxes that constitute the traditional experimental setups." Ulanovsky and his team understood that in order to attain a closer-to-natural take on spatial perception, they had to go bigger - a difference in scale, they hypothesized, should translate to a difference in neuronal activity.

To test their hypothesis, Ulanovsky initiated the construction of a 200 meters-long bat tunnel - an elongated opaque greenhouse of sorts - on the Weizmann Institute campus, the first of its kind in the world. "Although our tunnel is not exactly 20 kilometers long, 200 meters are still considerably more than what we were able to study so far," Ulanovsky states. Additionally, the researchers developed a miniature "neural logger" device that is mounted on the bats' heads for recording the activity of neurons in their hippocampus - the brain region responsible for memory storage, including spatial memory - while they're in flight. Ulanovsky and his team also installed a series of antennas, providing more accurate location capabilities than GPS, which are required for tracking the bats flying in the tunnel. Taken together, the researchers were now able to study their fluttering subjects in a setting that better emulates their natural behavior.

The new study was led by Ph.D students Tamir Eliav and Shir Maimon, together with Dr. Liora Las - an Associate Staff Scientist working with Ulanovsky - and it is published at a symbolic timing: exactly 50 years ago this year, John O'Keefe discovered place cells; a discovery that in 2014 would earn him a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Place cells are specialized neurons in the hippocampus, each of which was found to be activated when a lab animal enters a particular space in its environment, called the place field. A joint activation of many place cells builds up an inner map of the environment, enabling navigation. However, the work of O'Keefe and others was performed on rodents navigating in small environments, such as the one-by-one-meter box - so the place cells in their hippocampus could accommodate the required number of place fields, each corresponding to an area of about 10 centimeters in diameter. If indeed each place cell in the animal's hippocampus represents one singular small space in the environment, then bats would need about 1013-1015 neurons to carry out the correct computation for the span of their multi-kilometer flight routes - but their hippocampus has only about 105 neurons, and yet they still manage to navigate.

Owing to their unique experimental setup, Ulanovsky and his team were able to add a significant piece to the spatial cognition puzzle. They found that when bats navigate a large environment, place cells shift their behavior completely from the traditional model. First of all, it turned out that a single neuron can represent multiple place fields, rather than just one, as was thought in the past. On top of that, the size of each place field is not uniform and changes according to location, sometimes by a 20-fold difference. In other words, each neuron can be activated by several locations, and each represented location may differ dramatically in size, i.e. has a different resolution. This multi-field multi-scale coding scheme can explain the discrepancy left behind by the traditional model wherein more neurons are required for computing navigation than there actually are in the hippocampus. Interestingly, the same type of code was found from the very first day of the bats' exposure to the tunnel, and in both wild-born and lab-born bats - attesting to the robustness of the multi-field multi-scale representation of space.

To expand further on their empirical findings, Ulanovsky collaborated with theoreticians Prof. Misha Tsodyks, a departmental colleague from Weizmann, and Dr. Johnatan Aljadeff, a former postdoctoral fellow at Weizmann and now a Professor at the University of California in San Diego, to create a computerized simulation of the newly discovered code. By comparing this code to the traditional model they found that while in smaller environments there is no significant difference between the two in terms of the system's accuracy, the new code is far more efficient in larger environments, and the system performs fewer location errors. Further analysis by Ph.D student Gily Ginosar provided insight into why the multi-field multi-scale code is observed in large environments but not in small ones.

"Additional theoretical modeling supplied a potential mechanistic explanation as to how and where this code is formed in the mammalian hippocampus," Ulanovsky says. "We believe that our findings are applicable to spatial perception of very large environments across mammalian species, including humans."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Unraveling DNA packaging

2021-06-01

The genetic material of most organisms is carried by DNA, a complex organic molecule. DNA is very long -- for humans, the molecule is estimated to be about 2 m in length. In cells, DNA occurs in a densely packed form, with strands of the molecule coiled up in a complicated but efficient space-filling way. A key role in DNA's compactification is played by histones, structural-support proteins around which a part of a DNA molecule can wrap. The DNA-histone wrapping process is reversible -- the two molecules can unwrap and rewrap -- but little is known about the mechanisms at play. Now, by applying high-speed atomic-force microscopy (HS-AFM), Richard ...

Ethnically diverse research identifies more genetic markers linked to diabetes

2021-06-01

By ensuring ethnic diversity in a largescale genetic study, an international team of researchers, including a University of Massachusetts Amherst genetic epidemiologist, has identified more regions of the genome linked to type 2 diabetes-related traits.

The findings, published May 31 in Nature Genetics, broaden the understanding of the biological basis of type 2 diabetes and demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields better results. Ultimately the goal is to improve patient care worldwide by identifying genetic targets to treat the chronic metabolic disorder. Type 2 diabetes affects and sometimes debilitates more than 460 million adults worldwide, according to the International Diabetes Federation. About 1.5 million deaths were directly ...

Suitable thread type and stitch density for Ghanaian public basic school uniforms

2021-06-01

The quality of a sewn garment is dependent on the quality of its seams that are the basic structural element. The factors affecting seam quality in garments include sewing thread type and stitch density. Making the right choice of these helps in getting quality seams in garments. However, the choice of suitable sewing threads and stitch densities for particular fabrics can only be determined through testing.

Dr. Patience Danquah Monnie, from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, with fellow researchers, conducted research aimed to determine sewing thread brand and stitch density suitable for seams for a selected fabric (79% polyester and 21% cotton) for public basic school uniforms in Ghana. For the research, a 2×3 factorial ...

Scientists identify protein that activates plant response to nitrogen deficiency

2021-06-01

Nitrates are critical for the growth of plants, so plants have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to ensure sufficient nitrate uptake from their environments. In a new study published in Nature Plants, researchers at Nagoya University, Japan, have identified a plant enzyme that is key to activating a nitrate uptake mechanism in response to nitrogen starvation. This finding explains how plants meet their needs in challenging environments, opening doors to improving agriculture in such environments.

When nitrate levels are plentiful in a plant's environment, a plant can achieve adequate nitrate uptake levels by relying ...

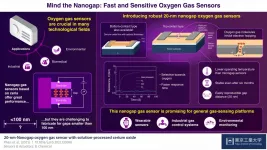

Mind the nanogap: Fast and sensitive oxygen gas sensors

2021-06-01

Oxygen (O2) is an essential gas not only for us and most other lifeforms, but also for many industrial processes, biomedicine, and environmental monitoring applications. Given the importance of O2 and other gases, many researchers have focused on developing and improving gas-sensing technologies. At the frontier of this evolving field lie modern nanogap gas sensors--devices usually comprised of a sensing material and two conducting electrodes that are separated by a minuscule gap in the order of nanometers (nm), or thousand millionths of a meter. When molecules of specific gases get inside this gap, they electronically interact with the sensing layer and the electrodes, altering measurable ...

Declining deer population likely due to natural regulation

2021-06-01

The Yakushima sika deer (yakushika: Cervus nippon yakushimae), a subspecies of the Japanese sika deer (Cervus nippon), evolved without natural predators on the island of Yakushima, in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. It inhabits the forests on the island which were declared a World Heritage Site in 1993. Within the site, the yakushika has not been hunted in the past 50 years; however, since 2014, their population has been decreasing. This phenomenon is especially curious, as Japanese researchers believed that sika deer populations in Japan would not decrease without human intervention.

A group of three scientists, including Hokkaido ...

Overweight or obesity worsens liver-damaging effects of alcohol

2021-06-01

Led by the University of Sydney's Charles Perkins Centre, the study looked at medical data from nearly half a million people and found having overweight or obesity considerably amplified the harmful effects of alcohol on liver disease and mortality.

"People in the overweight or obese range who drank were found to be at greater risk of liver diseases compared with participants within a healthy weight range who consumed alcohol at the same level," said senior author and research program director Professor Emmanuel Stamatakis from the Charles Perkins Centre and the Faculty of Medicine and Health.

"Even for people who drank within alcohol guidelines, participants classified as obese were at over 50 percent greater risk of liver disease."

The researchers ...

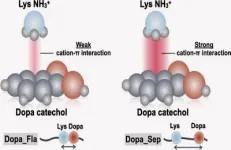

The secret to stickiness of mussels underwater

2021-06-01

Mussels survive by sticking to rocks in the fierce waves or tides underwater. Materials mimicking this underwater adhesion are widely used for skin or bone adhesion, for modifying the surface of a scaffold, or even in drug or cell delivery systems. However, these materials have not entirely imitated the capabilities of mussels.

A joint research team from POSTECH and Kangwon National University (KNU) - led by Professor Hyung Joon Cha and Ph.D. candidate Mincheol Shin of the Department of Chemical Engineering at POSTECH with Professor Young Mee Jeong and Dr. Yeonju Park of the Department ...

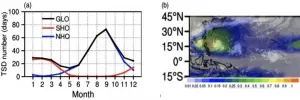

Researchers connect climate features to the variability of global tropical storm days from 1965 to 2019

2021-06-01

Nearly two billion people live in a region where tropical cyclones (TC) are an annual threat. TCs are deadly and can cause billions of dollars in economic losses worldwide. During peak season in the Northern Hemisphere, typically July through October, about two TCs develop or are ongoing every day. However, this and overall TC frequency vary substantially year-to-year.

To quantify this variability, scientists developed a metric called the tropical storm day (TSD). TSD is a collective measure of how frequently tropical cyclones develop, storm track, and cyclone lifespan, which reflects overall activity. Despite this advancement, researchers have not often studied tropical cyclone variability on a global scale.

Now, ...

Biopolymer-based electrolyte for the dream of zero-pollution battery

2021-06-01

In a paper published in NANO, researchers from Guizhou Meiling Power Sources Co., Ltd., China have reviewed the recent progress in biopolymer-based electrolyte. The biopolymer materials with unique characteristics including water solubility, film-forming capability and adhesive property played a key role in the design of zero pollution lithium battery. The biopolymers mentioned in this review were polysaccharide, protein, natural rubber and other polymers.

For polysaccharide, cellulose with good wettability, low cost and good mechanical properties can enhance the mechanical strength of membranes and improve interfacial stability between electrolyte and electrode. However, the porosity control of cellulose-based membranes was ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How stepping into nature affects the brain

Study: Cancer’s clues in the bloodstream reveal the role androgen receptor alterations play in metastatic prostate cancer

FAU Harbor Branch awarded $900,000 for Gulf of America sea-level research

Terminal ileum intubation and biopsy in routine colonoscopy practice

Researchers find important clue to healthy heartbeats

Characteristic genomic and clinicopathologic landscape of DNA polymerase epsilon mutant colorectal adenocarcinomas

Start school later, sleep longer, learn better

Many nations underestimate greenhouse emissions from wastewater systems, but the lapse is fixable

The Lancet: New weight loss pill leads to greater blood sugar control and weight loss for people with diabetes than current oral GLP-1, phase 3 trial finds

Pediatric investigation study highlights two-way association between teen fitness and confidence

Researchers develop cognitive tool kit enabling early Alzheimer's detection in Mandarin Chinese

New book captures hidden toll of immigration enforcement on families

New record: Laser cuts bone deeper than before

Heart attack deaths rose between 2011 and 2022 among adults younger than age 55

Will melting glaciers slow climate change? A prevailing theory is on shaky ground

New treatment may dramatically improve survival for those with deadly brain cancer

Here we grow: chondrocytes’ behavior reveals novel targets for bone growth disorders

Leaping puddles create new rules for water physics

Scientists identify key protein that stops malaria parasite growth

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

[Press-News.org] Right off the bat: Navigation in extra-large spacesBats navigating in an innovative extra-large experimental setup reveal an unknown neuronal code