(Press-News.org) New research from the Georgia Institute of Technology finds that elephants dilate their nostrils in order to create more space in their trunks, allowing them to store up to nine liters of water. They can also suck up three liters per second -- a speed 50 times faster than a human sneeze (150 meters per second/330 mph).

The Georgia Tech College of Engineering study sought to better understand the physics of how elephants use their trunks to move and manipulate air, water, food and other objects. They also sought to learn if the mechanics could inspire the creation of more efficient robots that use air motion to hold and move things.

While octopus use jets of water to move and archer fish shoot water above the surface to catch insects, the Georgia Tech researchers found that elephants are the only animals able to use suction on land and underwater.

The paper, "Suction feeding by elephants," is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

"An elephant eats about 400 pounds of food a day, but very little is known about how they use their trunks to pick up lightweight food and water for 18 hours, every day," said Georgia Tech mechanical engineering Ph.D. student Andrew Schulz, who led the study. "It turns out their trunks act like suitcases, capable of expanding when necessary."

Schulz and the Georgia Tech team worked with veterinarians at Zoo Atlanta, studying elephants as they ate various foods. For large rutabaga cubes, for example, the animal grabbed and collected them. It sucked up smaller cubes and made a loud vacuuming sound, or the sound of a person slurping noodles, before transferring the vegetables to its mouth.

To learn more about suction, the researchers gave elephants a tortilla chip and measured the applied force. Sometimes the animal pressed down on the chip and breathed in, suspending the chip on the tip of trunk without breaking it. It was similar to a person inhaling a piece of paper onto their mouth. Other times the elephant applied suction from a distance, drawing the chip to the edge of its trunk.

"An elephant uses its trunk like a Swiss Army Knife," said David Hu, Schulz's advisor and a professor in Georgia Tech's George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. "It can detect scents and grab things. Other times it blows objects away like a leaf blower or sniffs them in like a vacuum."

By watching elephants inhale liquid from an aquarium, the team was able to time the durations and measure volume. In just 1.5 seconds, the trunk sucked up 3.7 liters, the equivalent of 20 toilets flushing simultaneously.

An ultrasonic probe was used to take trunk wall measurements and see how the trunk's inner muscles work. By contracting those muscles, the animal dilates its nostrils up to 30 percent. This decreases the thickness of the walls and expands nasal volume by 64 percent.

"At first it didn't make sense: an elephant's nasal passage is relatively small and it was inhaling more water than it should," said Schulz. "It wasn't until we saw the ultrasonographic images and watched the nostrils expand that we realized how they did it. Air makes the walls open, and the animal can store far more water than we originally estimated."

Based on the pressures applied, Schulz and the team suggest that elephants inhale at speeds that are comparable to Japan's 300-mph bullet trains.

Schulz said these unique characteristics have applications in soft robotics and conservation efforts.

"By investigating the mechanics and physics behind trunk muscle movements, we can apply the physical mechanisms -- combinations of suction and grasping -- to find new ways to build robots," Schulz said. "In the meantime, the African elephant is now listed as endangered because of poaching and loss of habitat. Its trunk makes it a unique species to study. By learning more about them, we can learn how to better conserve elephants in the wild."

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the US Army Research Laboratory and the US Army Research O?ce 294 Mechanical Sciences Division, Complex Dynamics and Systems Program, under contract number 295 W911NF-12-R-0011. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the sponsoring agency.

CITATION: Schulz AK, et.al., "Suction feeding by Elelphants." (Journal of the Royal Society Interface 20210215) https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2021.0215

The Georgia Institute of Technology, or Georgia Tech, is a top 10 public research university developing leaders who advance technology and improve the human condition. The Institute offers business, computing, design, engineering, liberal arts, and sciences degrees. Its nearly 40,000 students representing 50 states and 149 countries, study at the main campus in Atlanta, at campuses in France and China, and through distance and online learning. As a leading technological university, Georgia Tech is an engine of economic development for Georgia, the Southeast, and the nation, conducting more than $1 billion in research annually for government, industry, and society.

Video link: END

Boulder, Colo., USA: Article topics include Zealandia, Earth's newly recognized continent; the topography of Scandinavia; an interfacial energy penalty; major disruptions in North Atlantic circulation; the Great Bahama Bank; Pityusa Patera, Mars; the end-Permian extinction; and Tongariro and Ruapehu volcanoes, New Zealand. These Geology articles are online at https://geology.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent.

Mass balance controls on sediment scour and bedrock erosion in waterfall plunge pools

Joel S. Scheingross; Michael P. Lamb

Abstract: Waterfall plunge pools experience cycles of sediment aggradation and scour that modulate ...

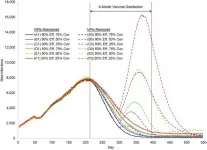

CHAPEL HILL, NC - Research published by JAMA Network Open shows how non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) like mask wearing and physical distancing can help prevent spikes in COVID-19 cases as populations continue to get vaccinated. The study, led by Mehul Patel, PhD, a clinical and population health researcher in the department of Emergency Medicine at the UNC School of Medicine, focuses on the state of North Carolina. Similar modeling studies have been used in different states, and can serve as guidance to leaders as they make decisions to relax restrictions and safety protocols.

"The computer simulation modeling allows us to look at multiple factors that play a role in decreasing the spread of COVID-19 as vaccines are ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- By delivering small electrical pulses directly to the brain, deep brain stimulation (DBS) can ease tremors associated with Parkinson's disease or help relieve chronic pain. The technique works well for many patients, but researchers would like to make DBS devices that are a little smarter by adding the capability to sense activity in the brain and adapt stimulation accordingly.

Now, a new algorithm developed by Brown University bioengineers could be an important step toward such adaptive DBS. The algorithm removes a key hurdle that makes it difficult for DBS systems to sense brain signals while simultaneously delivering stimulation.

"We know that there are electrical signals ...

Researchers in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences have developed a robotic mechanism for mushroom picking and trimming and demonstrated its effectiveness for the automated harvesting of button mushrooms.

In a new study, the prototype, which is designed to be integrated with a machine vision system, showed that it is capable of both picking and trimming mushrooms growing in a shelf system.

The research is consequential, according to lead author Long He, assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering, because the mushroom industry has been facing labor shortages and rising labor costs. Mechanical or robotic picking can help alleviate those problems.

"The mushroom industry in Pennsylvania is producing about two-thirds of the mushrooms ...

Older adults with cognitive impairment are two to three times more likely to fall compared with those without cognitive impairment. What's more, the increasing use of pain medications for chronic pain by older adults adds to their falls risk. Risks associated with falls include minor bruising to more serious hip fractures, broken bones and even head injuries. With falls a leading cause of injury for people aged 65 and older, it is an important public health issue to study in order to allow these adults increased safety and independence as they age.

Although elevated risk of falls due to use of pain medication by older adults has been widely studied, less ...

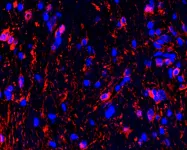

In a study of mice, researchers showed how the act of seeing light may trigger the formation of vision-harming tumors in young children who are born with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) cancer predisposition syndrome. The research team, funded by the National Institutes of Health, focused on tumors that grow within the optic nerve, which relays visual signals from the eyes to brain. They discovered that the neural activity which underlies these signals can both ignite and feed the tumors. Tumor growth was prevented or slowed by raising young mice in the dark or treating them with an experimental cancer drug during a critical period of cancer development.

"Brain cancers recruit the resources they need from the environment ...

Researchers world-wide are focused on clearing the toxic mutant Huntingtin protein that leads to neuronal cell death and systemic dysfunction in Huntington's disease (HD), a devastating, incurable, progressive neurodegenerative genetic disorder. Scientists in the Buck Institute's Ellerby lab have found that the targeting the protein called FK506-binding protein 51 or FKBP51 promotes the clearing of those toxic proteins via autophagy, a natural process whereby cells recycle damaged proteins and mitochondria and use them for nutrition.

Publishing in Autophagy , researchers showed that FKBP51 promotes autophagy through a new mechanism that could avoid worrisome side ...

Despite a name straight from a Tarantino movie, natural killer (NK) cells are your allies when it comes to fighting infections and cancer. If T cells are like a team of specialist doctors in an emergency room, NK cells are the paramedics: They arrive first on the scene and perform damage control until reinforcements arrive.

Part of our innate immune system, which dispatches these first responders, NK cells are primed from birth to recognize and respond to danger. Learning what fuels NK cells is an active area of research in immunology, with important clinical implications.

"There's a lot of interest right now ...

Army scientists working as part of an international consortium have developed and tested an antibody-based therapy to treat Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), which is carried by ticks and kills up to 60 percent of those infected. Their results are published online today in the journal Cell.

Using blood samples donated by disease survivors, the study's authors characterized the human immune response to natural CCHFV infection. They were able to identify several potent neutralizing antibodies that target the viral glycoprotein--a component of the virus that plays a key role ...

AMES, Iowa - An unexpected discovery by an Iowa State University researcher suggests that the first humans may have arrived in North America more than 30,000 years ago - nearly 20,000 years earlier than originally thought.

Andrew Somerville, an assistant professor of anthropology in world languages and cultures, says he and his colleagues made the discovery while studying the origins of agriculture in the Tehuacan Valley in Mexico. As part of that work, they wanted to establish a date for the earliest human occupation of the Coxcatlan Cave in the valley, so they obtained radiocarbon dates for several rabbit and deer bones that were collected from the cave in the 1960s as part of the Tehuacan Archaeological-Botanical Project. The dates for the bones suddenly ...