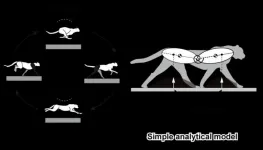

(Press-News.org) What makes cheetah the fastest land mammal? Why aren't other animals, such as horses, as fast? While we haven't yet figured out why, we have some idea about how--cheetahs, as it turns out, make use of a "galloping" gait at their fastest speeds, involving two different types of "flight": one with the forelimbs and hind limbs beneath their body following a forelimb liftoff, called "gathered flight," while another with the forelimbs and hind limbs stretched out after a hind limb liftoff, called "extended flight" (see Figure 1). Of these, the extended flight is what enables cheetahs to accelerate to high speeds, and it depends on ground reaction forces satisfying specific conditions; in the case of horses, the extended flight is absent.

Additionally, cheetahs show appreciable spine movement during flight, alternating between flexing and stretching in gathered and extended modes, respectively, which contributes to its high-speed locomotion. However, little is understood about the dynamics governing these abilities.

"All animal running constitutes a flight phase and a stance phase, with different dynamics governing each phase," explains Dr. Tomoya Kamimura from Nagoya Institute of Technology, Japan, who specializes in intelligent mechanics and locomotion. During the flight phase, all feet are in the air and the center of mass (COM) of the whole body exhibits ballistic motion. Conversely, during the stance phase, the body receives ground reaction forces through the feet. "Due to such complex and hybrid dynamics, observations can only get us so far in unraveling the mechanisms underlying the running dynamics of animals," Dr. Kamimura says.

Consequently, researchers have turned to computer modeling to gain a better dynamic perspective of the animal gait and spine movement during running and have had remarkable success using fairly simple models. However, few studies so far have explored the types of flight and spine motion during galloping (as seen in a cheetah). Against this backdrop, Dr. Kamimura and his colleagues from Japan have now addressed this issue in a recent study published in Scientific Reports, using a simple model emulating vertical and spine movement.

The team, in their study, employed a two-dimensional model comprising two rigid bodies and two massless bars (representing the cheetah's legs), with the bodies connected by a joint to replicate the bending motion of the spine and a torsional spring. Additionally, they assumed an anterior-posterior symmetry, assigning identical dynamical roles to the fore and hind legs.

By solving the simplified equations of motion governing this model, the team obtained six possible periodic solutions, with two of them resembling two different flight types (like cheetah galloping) and four, only one flight type (unlike cheetah galloping), based on the criteria related to the ground reaction forces provided by the solutions themselves. Researchers then verified these criteria with measured cheetah data, revealing that cheetah galloping in the real world indeed satisfied the criterion for two flight types through spine bending (see Figure 2).

Additionally, the periodic solutions also revealed that horse galloping only involves gathered flight due to restricted spine motion, suggesting that the additional extended flight in cheetahs combined with spine bending allowed them to achieve such great speeds!

"While the mechanism underlying this difference in flight types between animal species still remains unclear, our findings extend the understanding of the dynamic mechanisms underlying high-speed locomotion in cheetahs. Furthermore, they can be applied to the mechanical and control design of legged robots in the future," speculates an optimistic Dr. Kamimura.

Cheetahs inspiring legged robots! Who would've thought?

INFORMATION:

About Nagoya Institute of Technology, Japan

Nagoya Institute of Technology (NITech) is a respected engineering institute located in Nagoya, Japan. Established in 1949, the university aims to create a better society by providing global education and conducting cutting-edge research in various fields of science and technology. To this end, NITech provides a nurturing environment for students, teachers, and academicians to help them convert scientific skills into practical applications. Having recently established new departments and the "Creative Engineering Program," a 6-year integrated undergraduate and graduate course, NITech strives to continually grow as a university. With a mission to "conduct education and research with pride and sincerity, in order to contribute to society," NITech actively undertakes a wide range of research from basic to applied science.

Website: https://www.nitech.ac.jp/eng/index.html

About Dr. Tomoya Kamimura from Nagoya Institute of Technology, Japan

Dr. Tomoya Kamimura is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering at Nagoya Institute of Technology (NITech), Japan, and he has been working there since 2020. He specializes in intelligent mechanics/mechanical systems and his research interests include quadruped robot, simple model, and locomotion. As a young and vibrant researcher, he has 5 publications under his belt.

Developing vaccines against bacteria is in many cases much more difficult than vaccines against viruses. Like virtually all pathogens, bacteria are able to sidestep a vaccine's effectiveness by modifying their genes. For many pathogens, such genetic adaptations under selective pressure from vaccination will cause their virulence or fitness to decrease. This lets the pathogens escape the effects of vaccination, but at the price of becoming less transmissible or causing less damage. Some pathogens, however, including many bacteria, are extremely good at changing in ways that allow them to escape the effects of vaccination while remaining highly ...

The white-tailed sea eagle is known for reacting sensitively to human disturbances. Forestry and agricultural activities are therefore restricted in the immediate vicinity of the nests. However, these seasonal protection periods are too short in the German federal States of Brandenburg (until August 31) and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (until July 31), as a new scientific analysis by a team of scientists from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) suggests. Using detailed movement data of 24 juvenile white-tailed sea eagles with GPS transmitters, they were able to track when they fledge and when they leave the parental territory: on average, a good 10 and ...

Materials have a variety of properties that can be used to solve computational problems, according to studies in substrate-based computing. BZ computers, slime mould computers, plant computers, and collision-based liquid marbles computers are just a few examples of prototypes produced for future and emergent computing devices. Modelling the computational processes that exist in such systems, however, is a difficult task in general, and determining which part of the embodied system is doing the computation is still somewhat ill-defined.

Claiming that fungi are the most intelligent living organisms in the world sounds like an exaggeration. However, a recent study by Mohammad Mahdi Dehshibi, a UOC researcher who is contributing to a growing body of knowledge on the use of fungal materials, ...

Eating at least two serves of fruit daily has been linked with 36 percent lower odds of developing type 2 diabetes, a new Edith Cowan University (ECU) study has found.

The study, published today in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, revealed that people who ate at least two serves of fruit per day had higher measures of insulin sensitivity than those who ate less than half a serve.

Type 2 diabetes is a growing public health concern with an estimated 451 million people worldwide living with the condition. A further 374 million people are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

The study's lead author, Dr Nicola ...

Researchers at Linköping University in Sweden have developed an app to help women achieve a healthy weight gain and lifestyle during a pregnancy. The results from an evaluation of the app have now been published in two scientific articles. Using the app contributed to a better diet. Pregnant women with overweight or obesity who received the app also gained less weight during pregnancy.

"Pregnancy is a phase in life when many people try to do what is best for themselves and their baby. We think it's important to be able to offer a tool that has ...

Good acoustics in the workspace improve work efficiency and productivity, which is one of the reasons why acoustic materials matter. The acoustic insulation market is already expected to hit 15 billion USD by 2022 as construction firms and industry pay more attention to sound environments. Researchers at Aalto University, in collaboration with Finnish acoustics company Lumir, have now studied how these common elements around us could become more eco-friendly, with the help of cellulose fibres.

'Models for acoustic absorption are based on tests done with synthetic fibres, and ...

An international research team determined that ancestors of modern domestic horses and the Przewalski horse moved from the territory of Eurasia (Russian Urals, Siberia, Chukotka, and eastern China) to North America (Yukon, Alaska, continental USA) from one continent on another at least twice. It happened during the Late Pleistocene (2.5 million years ago - 11.7 thousand years ago). The analysis results are published in the journal. The findings and description of horse genomes are published in the journal Molecular Ecology.

"We found out that the Beringian Land Bridge, or the area known as Beringia, influenced genetic ...

All the cells of an organism share the same DNA sequence, but their functions, shapes or even lifespans vary greatly. This happens because each cell "reads" different chapters of the genome, thus producing alternative sets of proteins and embarking on different paths. Epigenetic regulation--DNA methylation is one of the most common mechanisms--is responsible for the activation or inactivation of a given gene in a specific cell, defining a secondary cell-specific genetic code.

Researchers led by Dr. Modesto Orozco, head of the Molecular Modelling and Bioinformatics lab at IRB Barcelona, have described how methylation has a protein-independent regulatory role by increasing the stiffness of DNA, which affects the 3D structure ...

Autistic people's ability to accurately identify facial expressions is affected by the speed at which the expression is produced and its intensity, according to new research at the University of Birmingham.

In particular, autistic people tend to be less able to accurately identify anger from facial expressions produced at a normal 'real world' speed. The researchers also found that for people with a related disorder, alexithymia, all expressions appeared more intensely emotional.

The question of how people with autism recognise and relate to emotional expression has been debated by scientists for more than three decades and it's only in the past 10 years ...

The gut and the brain communicate with each other in order to adapt satiety and blood sugar levels during food consumption. The vagus nerve is an important communicator between these two organs. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research in Cologne, the Cluster of Excellence for Ageing Research CECAD at the University of Cologne and the University Hospital Cologne now took a closer look at the functions of the different nerve cells in the control centre of the vagus nerve, and discovered something very surprising: although the nerve cells are located in the same control center, they innervate different regions of the gut and also differentially control satiety and blood sugar levels. This discovery could play an important role in the development of future ...