(Press-News.org) A 3D printer that rapidly produces large batches of custom biological tissues could help make drug development faster and less costly. Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego developed the high-throughput bioprinting technology, which 3D prints with record speed--it can produce a 96-well array of living human tissue samples within 30 minutes. Having the ability to rapidly produce such samples could accelerate high-throughput preclinical drug screening and disease modeling, the researchers said.

The process for a pharmaceutical company to develop a new drug can take up to 15 years and cost up to $2.6 billion. It generally begins with screening tens of thousands of drug candidates in test tubes. Successful candidates then get tested in animals, and any that pass this stage move on to clinical trials. With any luck, one of these candidates will make it into the market as an FDA approved drug.

The high-throughput 3D bioprinting technology developed at UC San Diego could accelerate the first steps of this process. It would enable drug developers to rapidly build up large quantities of human tissues on which they could test and weed out drug candidates much earlier.

"With human tissues, you can get better data--real human data--on how a drug will work," said Shaochen Chen, a professor of nanoengineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. "Our technology can create these tissues with high-throughput capability, high reproducibility and high precision. This could really help the pharmaceutical industry quickly identify and focus on the most promising drugs."

The work was published in the journal Biofabrication.

The researchers note that while their technology might not eliminate animal testing, it could minimize failures encountered during that stage.

"What we are developing here are complex 3D cell culture systems that will more closely mimic actual human tissues, and that can hopefully improve the success rate of drug development," said Shangting You, a postdoctoral researcher in Chen's lab and co-first author of the study.

The technology rivals other 3D bioprinting methods not only in terms of resolution--it prints lifelike structures with intricate, microscopic features, such as human liver cancer tissues containing blood vessel networks--but also speed. Printing one of these tissue samples takes about 10 seconds with Chen's technology; printing the same sample would take hours with traditional methods. Also, it has the added benefit of automatically printing samples directly in industrial well plates. This means that samples no longer have to be manually transferred one at a time from the printing platform to the well plates for screening.

"When you're scaling this up to a 96-well plate, you're talking about a world of difference in time savings--at least 96 hours using a traditional method plus sample transfer time, versus around 30 minutes total with our technology," said Chen.

Reproducibility is another key feature of this work. The tissues that Chen's technology produces are highly organized structures, so they can be easily replicated for industrial scale screening. It's a different approach than growing organoids for drug screening, explained Chen. "With organoids, you're mixing different types of cells and letting them to self-organize to form a 3D structure that is not well controlled and can vary from one experiment to another. Thus, they are not reproducible for the same property, structure and function. But with our 3D bioprinting approach, we can specify exactly where to print different cell types, the amounts and the micro-architecture."

How it works

To print their tissue samples, the researchers first design 3D models of biological structures on a computer. These designs can even come from medical scans, so they can be personalized for a patient's tissues. The computer then slices the model into 2D snapshots and transfers them to millions of microscopic-sized mirrors. Each mirror is digitally controlled to project patterns of violet light--405 nanometers in wavelength, which is safe for cells--in the form of these snapshots. The light patterns are shined onto a solution containing live cell cultures and light-sensitive polymers that solidify upon exposure to light. The structure is rapidly printed one layer at a time in a continuous fashion, creating a 3D solid polymer scaffold encapsulating live cells that will grow and become biological tissue.

The digitally controlled micromirror array is key to the printer's high speed. Because it projects entire 2D patterns onto the substrate as it prints layer by layer, it produces 3D structures much faster than other printing methods, which scans each layer line by line using either a nozzle or laser.

"An analogy would be comparing the difference between drawing a shape using a pencil versus a stamp," said Henry Hwang, a nanoengineering Ph.D. student in Chen's lab who is also co-first author of the study. "With a pencil, you'd have to draw every single line until you complete the shape. But with a stamp, you mark that entire shape all at once. That's what the digital micromirror device does in our technology. It's orders of magnitude difference in speed."

This recent work builds on the 3D bioprinting technology that Chen's team invented in 2013. It started out as a platform for creating living biological tissues for regenerative medicine. Past projects include 3D printing liver tissues, blood vessel networks, heart tissues and spinal cord implants, to name a few. In recent years, Chen's lab has expanded the use of their technology to print coral-inspired structures that marine scientists can use for studying algae growth and for aiding coral reef restoration projects.

Now, the researchers have automated the technology in order to do high-throughput tissue printing. Allegro 3D, Inc., a UC San Diego spin-off company co-founded by Chen and a nanoengineering Ph.D. alumnus from his lab, Wei Zhu, has licensed the technology and recently launched a commercial product.

INFORMATION:

Paper: "High throughput direct 3D bioprinting in multiwell plates." Co-authors include Xuanyi Ma, Leilani Kwe, Grace Victorine, Natalie Lawrence, Xueyi Wan, Haixu Shen and Wei Zhu.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01EB021857, R21AR074763, R21HD100132, R33HD090662) and the National Science Foundation (1903933, 1937653).

NEW YORK, NY--A new global study of 30-day outcomes in children and adolescents with COVID-19 found that while death was uncommon, the illness produced more symptoms and complications than seasonal influenza.

The study, "30-day outcomes of Children and Adolescents with COVID-19: An International Experience," published online in the journal Pediatrics, also found significant variation in treatment of children and adolescents hospitalized with COVID-19.

Early in the pandemic, opinions around the impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescents ranged from it being no more than the common flu to fear of its potential impact on lesser-developed immune systems. This OHDSI global network study compared the real-world observational data of more ...

The emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle native to Southeast Asia, threatens the entire ash tree population in North America and has already changed forested landscapes and caused tens of billions of dollars in lost revenue to the ash sawtimber industry since it arrived in the United States in the 1990s. Despite the devastating impact the beetle has had on forests in the eastern and midwestern parts of the U.S., climate change will have a much larger and widespread impact on these landscapes through the end of the century, according to researchers.

"We really wanted to focus on isolating the impact of the emerald ash borer ...

An experimental, lab-made antibody can completely prevent nonhuman primates from being infected with the monkey form of HIV, new research published in Nature Communications shows.

The results will inform a future human clinical trial evaluating leronlimab as a potential pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, therapy to prevent human infection from the virus that causes AIDS.

"Our study findings indicate leronlimab could be a new weapon against the HIV epidemic," said the study's lead researcher and co-corresponding author of this paper, Jonah Sacha, Ph.D., an Oregon Health & Science University professor at OHSU's Oregon National Primate Center and Vaccine & Gene Therapy Institute.

"The results of this pre-clinical ...

Cambridge, UK, 7th June 2021: The Cambridge Research Laboratory of Toshiba Europe today announced the first demonstration of quantum communications over optical fibres exceeding 600 km in length. The breakthrough will enable long distance quantum-secured information transfer between metropolitan areas and is a major advance towards building the future Quantum Internet.

The term Quantum Internet describes a global network of quantum computers connected by long distance quantum communication links. It is expected to allow the ultrafast solution of complex optimization problems ...

An international group of researchers has developed a new technique that could be used to make more efficient low-cost light-emitting materials which are flexible and can be printed using ink-jet techniques.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge and the Technical University of Munich, found that by swapping one out of every one thousand atoms of one material for another, they were able to triple the luminescence of a new material class of light emitters known as halide perovskites.

This 'atom swapping', or doping, causes the charge ...

Heart attacks and strokes -- the leading causes of death in human beings -- are fundamentally blood clots of the heart and brain. Better understanding how the blood-clotting process works and how to accelerate or slow down clotting, depending on the medical need, could save lives.

New research by the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University published in the journal Biomaterials sheds new light on the mechanics and physics of blood clotting through modeling the dynamics at play during a still poorly understood phase of blood clotting called clot contraction.

"Blood clotting is actually a physics-based phenomenon that must occur to stem bleeding after ...

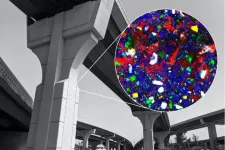

The concrete world that surrounds us owes its shape and durability to chemical reactions that start when ordinary Portland cement is mixed with water. Now, MIT scientists have demonstrated a way to watch these reactions under real-world conditions, an advance that may help researchers find ways to make concrete more sustainable.

The study is a "Brothers Lumière moment for concrete science," says co-author Franz-Josef Ulm, professor of civil and environmental engineering and faculty director of the MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub, referring to the two brothers who ushered in the era of projected films. Likewise, Ulm says, the MIT team has provided a glimpse of early-stage cement hydration that is like cinema in Technicolor ...

A new technology could dramatically improve the safety of lithium-ion batteries that operate with gas electrolytes at ultra-low temperatures. Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego developed a separator--the part of the battery that serves as a barrier between the anode and cathode--that keeps the gas-based electrolytes in these batteries from vaporizing. This new separator could, in turn, help prevent the buildup of pressure inside the battery that leads to swelling and explosions.

"By trapping gas molecules, this separator can function as a stabilizer for volatile electrolytes," said Zheng Chen, a ...

To describe something as slow and boring we say it's "like watching grass grow", but scientists studying the early morning activity of plants have found they make a rapid start to their day - within minutes of dawn.

Just as sunrise stimulates the dawn chorus of birds, so too does sunrise stimulate a dawn burst of activity in plants.

Early morning is an important time for plants. The arrival of light at the start of the day plays a vital role in coordinating growth processes in plants and is the major cue that keeps the inner clock of plants in rhythm with day-night cycles.

This inner circadian clock helps plants prepare for the day such as when to make the best use of sunlight, the best time to open flowers ...

Citizen opposition to COVID-19 vaccination has emerged across the globe, prompting pushes for mandatory vaccination policies. But a new study based on evidence from Germany and on a model of the dynamic nature of people's resistance to COVID-19 vaccination sounds an alarm: mandating vaccination could have a substantial negative impact on voluntary compliance.

Majorities in many countries now favor mandatory vaccination. In March, the government of Galicia in Spain made vaccinations mandatory for adults, subjecting violators to substantial fines. Italy has made vaccinations mandatory for care workers. The University of California and California State University systems announced in late April that vaccination ...