(Press-News.org) Lanthanides are rare-earth heavy metals with useful magnetic properties and a knack for emitting light. Researchers had long assumed that lanthanides' toxicity risk was low and therefore safe to implement in a number of high-tech breakthroughs we now take for granted: from OLEDs (organic light-emitting displays)¬¬ to medical MRIs and even hybrid vehicles.

In recent years, however, some scientists have questioned lanthanides' safety. In matters concerning health care, for example, some MRI patients have attributed a litany of side effects, including long-term kidney damage, to their exposure to the lanthanide gadolinium, a commonly used MRI contrast agent. And in the wake of landmark studies showing that gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) linger in patients' kidneys, bone and brain tissue for months if not years, scientists have searched for clearer evidence linking lanthanide exposure to disease.

But what's slowing scientists down is that they don't know where to start - there are 15 lanthanide elements, and the human genome consists of billions of nucleotide sequences. Understanding how lanthanides might trigger gene mutations associated with cancer and other diseases would require a dataset of mammoth proportions that doesn't yet exist.

Now, a team of researchers led by the Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and UC Berkeley has compiled the most complete library yet of lanthanides and their potential toxicity - by exposing baker's yeast, aka Saccharomyces cerevisiae, to lanthanide metals. Their findings were recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Like us, yeasts are eukaryotes - organisms made up of membrane-bound cells whose chromosomes are neatly packaged in a nucleus. We are made up of tens of trillions of cells; yeasts are just one cell.

"Yeast is the smallest eukaryote - but their thousands of genes represent a great approximation to the gene variants in humans," said senior author Rebecca Abergel, who holds titles of faculty scientist in the Chemical Sciences Division at Berkeley Lab, where she heads the BioActinide Chemistry Group, and assistant professor of nuclear engineering at UC Berkeley. "What's cool about this study is that it was done with a library of yeast genes, and we could screen the whole genome of the yeast and compare how a normal gene strain versus a gene-deletion strain was actually affected by lanthanide exposure."

In an investigation spanning nearly a decade, Abergel and her team relied on a barcoded library of the baker's yeast genome to screen which cellular functions were disrupted by lanthanides. The library was developed in the early 2000s as part of the Yeast Deletion Project, a consortium of researchers across the U.S. and Canada, to establish relationships between genes and chemical exposures. Co-senior author Christopher Vulpe, a professor of physiological sciences at the University of Florida, is one of the early adopters of this library for functional profiling of various toxicants.

After testing over 4,000 genes against 13 of the 15 lanthanide metals (the study excluded cerium and promethium), the researchers found that lanthanides interrupt the cell-signaling pathways that keep our bodies functioning - such as our skeletal and neurological processes - by hijacking calcium-binding sites in two key cellular activities: endocytosis, the process that governs how nutrients are imported inside the cells, and the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) machinery, which sorts proteins and helps cells shuttle in critical nutrients like calcium.

"This study could point us to understanding which lanthanide metals are more toxic than others, and whether someone is more genetically predisposed to lanthanide toxicity," Abergel said.

Abergel's investigation of baker's yeast as a genomic model for human disease began in 2012, when she was awarded a Berkeley Lab LDRD (Laboratory Directed Research and Development) Award for her study titled "Global transcriptome, deletome and proteome profiling of yeast exposed to radioactive metal ions: a tool to distinguish radiation-induced damage from chemical toxicity." Her interest in public health then led to the development of an anti-radiation-poisoning pill, an anti-gadolinium-toxicity pill for MRI patients, and advances in cancer therapies and medical imaging.

As a follow-up to the current study, she and her research team are now studying the toxicity mechanisms of each specific metal, beginning with gadolinium. They also hope to investigate in animal models how cellular abnormalities caused by lanthanide exposure are sustained over time - and possibly even across generations.

"This was a massive study showing all the potential pathways affected by lanthanide metal exposure - but we're just scratching the surface of a huge dataset" and there's much more work to be done, she said.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors on the paper include Roger Pallares (lead author), David Faulkner, Dahlia An, Solene Hebert, Alex Loguinov, Michael Proctor, Jonathan Villalobos, Kathleen Bjornstad, and Chris Rosen.

This work was supported by DOE's Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program. Additional supported was provided by generous donations from anonymous donors through the Berkeley Lab Foundation.

Most fish rely on water to feed, using suction to capture their prey. A new study, however, shows that snowflake morays can grab and swallow prey on land without water thanks to an extra set of jaws in their throats.

After a moray eel captures prey with its first set of jaws, a second set of "pharyngeal jaws" then reaches out to grasp the struggling prey and pull it down into the moray's throat. Rita Mehta, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz, first described this astonishing feeding mechanism in a 2007 Nature paper.

The new study, published June 7 in the Journal of Experimental Biology, shows that these pharyngeal jaws enable ...

Forty years ago, the first cases of HIV/AIDS in the U.S began to raise public awareness- but new research highlights the struggle people living with the disease still face against stigma, discrimination and negative labelling in their own families, communities and even amongst healthcare professionals.

A new study by Flinders University researchers interviewed 20 HIV healthcare providers including doctors, nurses, and counsellors in Yogyakarta and Belu districts, Indonesia to examine their experiences when treating patients with HIV. Their responses indicated admission of ...

A trial using mice has shown that a diet high in sugar from childhood could lead to significant weight gain, persistent hyperactivity and learning impairments

Many people on 'western' diets consume four times more the sugar recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO)

Reducing sucrose intake in mice by four-fold prevented sugar-induced increase in weight gain, supporting the WHO's recommendations of 25g per person a day.

Children who consume too much sugar could be at greater risk of becoming obese, hyperactive, and cognitively impaired, as adults, according to the results of a new study of mice led by ...

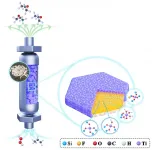

Propylene oxide (PO) is one of the important propylene derivatives with high reactivity, which is used extensively as raw material for the manufacture of numerous commercial chemicals. The titanosilicate-catalyzed hydrogen peroxide propylene oxide process (HPPO) is considered to be most advantageous because it is highly economical and ecofriendly, giving only H2O as the theoretical byproduct and achieving high PO selectivity under mild reaction conditions. The industrial HPPO process is generally carried out in a fixed-bed reactor using the shaped titanosilicate catalysts. Unfortunately, the inert and non-porous binders in shaping ...

The geometric isolation of metal species in single-atom catalysis (SACs) not only maximizes the atomic utilization efficiency, but also endows SACs with unique selectivity in various transformations.

The coordination environment of isolated metal atoms in SACs determines the catalytic performance. However, it remains challenging to modulate the coordinative structure while still maintain the single-atom dispersion.

Recently, a research group led by Prof. ZHANG Tao and Prof. WANG Aiqin from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences fabricated Ru1/NC ...

CHICAGO --- Having trouble falling or staying asleep may leave you feeling tired and frustrated. It also could subtract years from your life expectancy, according to a new study from Northwestern Medicine and the University of Surrey in the United Kingdom (UK).

The effect was even greater for people with diabetes who experienced sleep disturbances, the study found. Study participants with diabetes who experienced frequent sleep disturbances were 87% more likely to die of any cause (car accident, heart attack, etc.) during the 8.9-year study follow-up period compared to people without diabetes or sleep disturbances. They were 12% more likely to die over this period than those who had diabetes but not frequent sleep disturbances.

"If you don't have diabetes, your sleep ...

In a paper published by the Journal of Sleep Research, researchers reveal how they examined data* from half a million middle-aged UK participants asked if they had trouble falling asleep at night or woke up in the middle of the night.

The report found that people with frequent sleep problems are at a higher risk of dying than those without sleep problems. This grave outcome was more pronounced for people with Type-2 diabetes: during the nine years of the research, the study found that they were 87 per cent more likely to die of any cause than people without diabetes ...

Durham, NC - Critically ill COVID-19 patients treated with non-altered stem cells from umbilical cord connective tissue were more than twice as likely to survive as those who did not have the treatment, according to a study published today in STEM CELLS Translational Medicine.

The clinical trial, carried out at four hospitals in Jakarta, Indonesia, also showed that administering the treatment to COVID-19 patients with an added chronic health condition such as diabetes, hypertension or kidney disease increased their survival more than fourfold.

All 40 patients who took part in the double-blind, controlled, ...

A new study from the University of California, Davis and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai confirms that surgical masks effectively reduce outgoing airborne particles from talking or coughing, even after allowing for leakage around the edges of the mask. The results are published June 8 in Scientific Reports.

Wearing masks and other face coverings can reduce the flow of airborne particles that are produced during breathing, talking, coughing or sneezing, protecting others from viruses carried by those particles such as SARS-CoV2 and influenza, said Christopher Cappa, professor ...

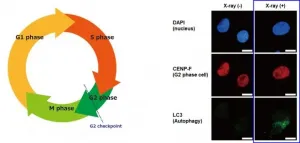

Of all the different types of cancer known, a subtype of pancreatic cancer called pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is among the most aggressive and deadly. This disease begins in the cells that make up certain small ducts in the pancreas and progresses silently, usually causing no symptoms until advanced tumors actually obstruct these ducts or spread to other places. PDAC is not only difficult to diagnose, but also very unresponsive to available treatments. In particular, researchers have noted that PDAC cells can usually survive radiotherapy through mechanisms that remain largely unknown.

Part of the Radiation and Cancer Biology ...