The new species, named Oculudentavis naga in honor of the Naga people of Myanmar and India, is represented by a partial skeleton that includes a complete skull, exquisitely preserved in amber with visible scales and soft tissue. The specimen is in the same genus as Oculudentavis khaungraae, whose original description as the smallest known bird was retracted last year. The two fossils were found in the same area and are about 99 million years old.

Researchers published their findings in Current Biology today.

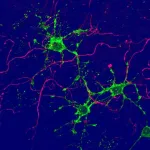

The team, led by Arnau Bolet of Barcelona's Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, used CT scans to separate, analyze and compare each bone in the two species digitally, uncovering a number of physical characteristics that earmark the small animals as lizards. Oculudentavis is so strange, however, it was difficult to categorize without close examination of its features, Bolet said.

"The specimen puzzled all of us at first because if it was a lizard, it was a highly unusual one," he said in an institutional press release.

Bolet and fellow lizard experts from around the world first noted the specimen while studying a collection of amber fossils acquired from Myanmar by gemologist Adolf Peretti. (Note: The mining and sale of Burmese amber are often entangled with human rights abuses. Peretti purchased the fossil legally prior to the conflict in 2017. More details appear in an ethics statement at the end of this story).

Herpetologist Juan Diego Daza examined the small, unusual skull, preserved with a short portion of the spine and shoulder bones. He, too, was confused by its odd array of features: Could it be some kind of pterodactyl or possibly an ancient relative of monitor lizards?

"From the moment we uploaded the first CT scan, everyone was brainstorming what it could be," said Daza, assistant professor of biological sciences at Sam Houston State University. "In the end, a closer look and our analyses help us clarify its position."

Major clues that the mystery animal was a lizard included the presence of scales; teeth attached directly to its jawbone, rather than nestled in sockets, as dinosaur teeth were; lizard-like eye structures and shoulder bones; and a hockey stick-shaped skull bone that is universally shared among scaled reptiles, also known as squamates.

The team also determined both species' skulls had deformed during preservation. Oculudentavis khaungraae's snout was squeezed into a narrower, more beaklike profile while O. naga's braincase - the part of the skull that encloses the brain - was compressed. The distortions highlighted birdlike features in one skull and lizard-like features in the other, said study co-author Edward Stanley, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History's Digital Discovery and Dissemination Laboratory.

"Imagine taking a lizard and pinching its nose into a triangular shape," Stanley said. "It would look a lot more like a bird."

Oculudentavis' birdlike skull proportions, however, do not indicate that it was related to birds, said study co-author Susan Evans, professor of vertebrate morphology and paleontology at University College London.

"Despite presenting a vaulted cranium and a long and tapering snout, it does not present meaningful physical characters that can be used to sustain a close relationship to birds, and all of its features indicate that it is a lizard," she said.

While the two species' skulls do not closely resemble one another at first glance, their shared characteristics became clearer as the researchers digitally isolated each bone and compared them with each other. The differences were minimized when the original shape of both fossils was reconstructed through a painstaking process known as retrodeformation, conducted by Marta Vidal-García from the University of Calgary in Canada.

"We concluded that both specimens are similar enough to belong to the same genus, Oculudentavis, but a number of differences suggest that they represent separate species," Bolet said.

In the better-preserved O. naga specimen, the team was also able to identify a raised crest running down the top of the snout and a flap of loose skin under the chin that may have been inflated in display, Evans said. However, the researchers came up short in their attempts to find Oculudentavis' exact position in the lizard family tree.

"It's a really weird animal. It's unlike any other lizard we have today," Daza said. "We think it represents a group of squamates we were not aware of."

The Cretaceous Period, 145.5 to 66 million years ago, gave rise to many lizard and snake groups on the planet today, but tracing fossils from this era to their closest living relatives can be difficult, Daza said.

"We estimate that many lizards originated during this time, but they still hadn't evolved their modern appearance," he said. "That's why they can trick us. They may have characteristics of this group or that one, but in reality, they don't match perfectly."

The majority of the study was conducted with CT data created at the Australian Centre for Neutron Scattering and the High-Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography Facility at the University of Texas at Austin. O. naga is now available digitally to anyone with Internet access, which allows the team's findings to be reassessed and opens up the possibility of new discoveries, Stanley said.

"With paleontology, you often have one specimen of a species to work with, which makes that individual very important. Researchers can therefore be quite protective of it, but our mindset is 'Let's put it out there,'" Stanley said. "The important thing is that the research gets done, not necessarily that we do the research. We feel that's the way it should be."

While Myanmar's amber deposits are a treasure trove of fossil lizards found nowhere else in the world, Daza said the consensus among paleontologists is that acquiring Burmese amber ethically has become increasingly difficult, especially after the military seized control in February.

"As scientists we feel it is our job to unveil these priceless traces of life, so the whole world can know more about the past. But we have to be extremely careful that during the process, we don't benefit a group of people committing crimes against humanity," he said. "In the end, the credit should go to the miners who risk their lives to recover these amazing amber fossils."

Other study co-authors are J. Salvador Arias of Argentina's National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET - Miguel Lillo Foundation); Andrej Cernansky of Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia; Aaron Bauer of Villanova University; Joseph Bevitt of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation; and Adolf Peretti of the Peretti Museum Foundation in Switzerland.

A 3D digitized specimen of O. naga is available online via MorphoSource. The O. naga fossil is housed at the Peretti Museum Foundation in Switzerland, and the O. khaungraae specimen is at the Hupoge Amber Museum in China.

The specimen was acquired following the ethical guidelines for the use of Burmese amber set forth by the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology. The specimen was purchased from authorized companies that are independent from military groups. These companies export amber pieces legally from Myanmar, following an ethical code that ensures no violations of human rights were committed during mining and commercialization and that money derived from sales did not support armed conflict. The fossil has an authenticated paper trail, including export permits from Myanmar. All documentation is available from the Peretti Museum Foundation upon request.

INFORMATION: