(Press-News.org) These are the findings of an Imperial-led study using data from thousands of children in England over a number of years, which looked at the health impact of consuming ultra-processed foods (UPFs) - food and drink heavily processed during their making, such as frozen pizzas, fizzy drinks, mass-produced packaged bread and some ready meals.

Researchers found that not only do UPFs make up a considerably high proportion of children's diets (more than 40% of intake in grams and more than 60% of calories on average), but that the higher the proportion of UPFs they consume, the greater the risk of becoming overweight or obese.

In addition, they highlight that eating patterns established in childhood extend into adulthood, potentially setting children on a lifelong trajectory for obesity and a range of negative physical and mental health outcomes including diabetes and cancers.

The authors explain the research, published today in the journal JAMA Pediatrics, provides important evidence of the potential damage of consuming highly processed foods which are often cheap, widely available and highly marketed. They say that action is needed urgently to reduce UPF consumption among children.

Professor Christopher Millett, NIHR Professor of Public Health at Imperial College London, said: "We often ask why obesity rates are so high among British children and this study provides a window into this. Our findings show that an exceptionally high proportion of their diet is made up of ultra-processed foods, with one in five children consuming 78% of their calories from ultra-processed foods.

"Through a lack of regulation, and enabling the low cost and ready availability of these foods, we are damaging our children's long-term health. We urgently need effective policy change to redress the balance, to protect the health of children and reduce the proportion of these foods in their diet."

Dr Eszter Vamos, Senior Clinical Lecturer in Public Health Medicine at Imperial, said: "One of the key things we uncover here is a dose-response relationship. This means that it's not only the children who eat the most ultra-processed foods have the worst weight gain, but also the more they eat, the worse this gets."

"Childhood is a critical time when food preferences and eating habits are formed with long-lasting effects on health. We know that if children have an unhealthy weight early in life, this tends to trace into adolescence and then adulthood. We also know that an excessive consumption of ultra-processed foods is linked to a number of health issues including being overweight or obese, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, type two diabetes and cancer later in life, so the implications are enormous."

This latest study provides new, important data on the impact of industrial food processing, in which foods are modified to change their consistency, taste, colour, shelf life or other attributes through mechanical or chemical alteration - typically lacking in traditional, home-prepared meals - on child health.

Led by a team from Imperial's School of Public Health, the work is the first to look at the link between the consumption of UPFs and obesity in children over a long period of time, with findings broadly applicable to children across the UK.

Using data from a cohort of 9,000 children in the Avon area in the West of England born in the early 1990s, researchers were able to follow the life course of children from the age of 7 until the age of 24. As part of this cohort, food diaries were completed at age 7, 10 and 13, recording the food and beverages children consumed over three days. Data measures were also collected over 17 years, covering areas including body mass index (BMI), weight, waist circumference and measurements of body fat.

Researchers categorised children into five equally-sized groups based on the consumption of UPFs in their diet - in the lowest group UPFs accounted for one fifth (23.2% of grams) of total diet, while the highest group consumed more than two-thirds of UPFs (67.8% of grams). Major sources of UPFs in the highest consumption group included fruit-based or fizzy drinks, ready meals, and mass-produced packaged bread and cakes. Comparatively, diets in the lowest consumption group were based on minimally processed foods and beverages, such as plain yogurt, water and fruit.

The analysis revealed that on average, children in the higher consumption groups saw a more rapid progression of their BMI, weight, waist circumference and body fat into adolescence and early adulthood. By 24 years of age, those in the highest UPF group had, on average, a higher level of BMI by 1.2 kg/m2, body fat by 1.5%, weight by 3.7 kg and waist circumference by 3.1 cm.

Kiara Chang, Research Fellow and first author on the paper, said: "During the 17 years of follow up, we saw a very consistent increase in all measures of unhealthy weight among children who consumed greater amounts of ultra-processed foods as part of their diet. Their BMI, weight gain, and body fat gain was much quicker than those children consuming less ultra-processed foods. We actually see it making a difference from as young as 9 years old, between those consuming the most compared with those consuming the least ultra-processed foods."

The researchers highlight that a limitation of the study is its observational nature, and that they are unable to definitively show direct causation between consumption of UPFs and increases in BMI and body fat.

According to the researchers, more radical and effective public health actions are needed urgently to reduce children's exposure and consumption of UPFs and to address childhood obesity in the UK and internationally. These actions should include:

National dietary guidelines should be updated to emphasise preference for fresh or minimally processed foods and avoidance of ultra-processed foods, in line with guidelines developed in Brazil, Uruguay, France, Belgium and Israel.

UPFs should be taxed and minimally processed foods should be subsidised to make healthier food choices more affordable. Other actions include restricting promotions and all forms of advertising of UPFs, especially those targeting children, and mandatory bold front-of-pack product labelling.

They add that further studies are now needed to determine the underlying mechanisms linking UPF consumption to worse health outcomes. Hypotheses include that UPFs produce lower satiety, meaning that people do not feel full after eating these products, encouraging excess consumption. More research is also needed to explore whether additives in highly processed food interfere with biological processes, such as hormones influencing appetite and glucose control.

Professor Millett featured in the recent BBC One documentary 'What Are We Feeding Our Kids?', in which he said: "Today in Britain, two in every three calories consumed amongst children and adolescents is derived from this group [of ultra-processed foods]. They're everywhere, they're cheap, and they're heavily marketed. So they're very difficult to resist and very difficult to avoid."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR). The team also highlights support from the STOP project, funded through EU Horizon 2020.

'Association Between Childhood Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Adiposity Trajectories in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Birth Cohort' by Chang, K. et al. is published in JAMA Pediatrics. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1573

'What Are We Feeding Our Kids?' was broadcast on BBC One on 27 May 2021. It is currently available on BBC iPlayer.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000wgcd/what-are-we-feeding-our-kids

Coronavirus disruption to weddings has highlighted the complexity and antiquity of marriage law and reinforced the need for reform, a new study shows.

During the pandemic the ease and speed with which couples were able to marry has depended on their chosen route into marriage - religious or civil - experts have found.

Rules to prevent the spread of the pandemic attempted to strike a balance between getting married as a legal event and a wedding as a social event, and this has failed to please anyone, according to the research.

As lockdown loomed, couples marrying in the Anglican church were able to apply for a common or special licence rather than waiting to ...

LOUISVILLE, Ky. - A clinical trial conducted at the University of Louisville has shown for the first time that heart failure treatments using cells derived from the patient's own bone marrow and heart resulted in improved quality of life and reduced major adverse cardiac events for patients after one year.

"This is a very important advance in the field of cell therapy and in the management of heart failure. It suggests that a treatment, given only once, can produce long-term beneficial effects on the quality of life and prognosis of these patients," said Roberto Bolli, M.D., ...

HOUSTON - (June 11, 2021) - Scientific studies describing the most basic processes often have the greatest impact in the long run. A new work by Rice University engineers could be one such, and it's a gas, gas, gas for nanomaterials.

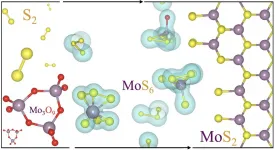

Rice materials theorist Boris Yakobson, graduate student Jincheng Lei and alumnus Yu Xie of Rice's Brown School of Engineering have unveiled how a popular 2D material, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), flashes into existence during chemical vapor deposition (CVD).

Knowing how the process works will give scientists and engineers a way to optimize the bulk manufacture ...

RUDN University scientists together with colleagues from Switzerland proved in a clinical trial the effectiveness of a new dosage form -- amorphous solid dispersion. This is the first such study in humans to show the mechanism of action of this form of drug release. In the future, it will help to increase the effectiveness of drugs and use new active substances for treatment. The results of the study are published in Pharmaceuticals.

One of the main reasons for the dropout of new oral drugs at the preclinical and clinical stages of development is low bioavailability. The drug itself can be effective, but it is poorly absorbed in the body because of its low solubility. Amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) is a new ...

The 17-year cicadas emerging dramatically by the billions in 15 U.S. states from Georgia to New York and west to Illinois are making quite a racket--a uniquely North American phenomenon--but thousands of other cicada species on the planet also spend most of their lives underground, many of them emerging below the radar of human perception. Because most cicada species don't emerge simultaneously like species in the genus Magicicada--the periodical cicadas--little is known about their natural history. Driven by unusual attention to detail and curiosity, Annette Aiello, staff entomologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama, joined a very select group of ...

Environmental bacteria and fungi that end up in the belly of honeybees may be essential to their survival in a changing world as bee populations dwindle due to pesticides, poor nutrition, habitat destruction and declining genetic diversity.

Like many animals, bees have an internal armory. Their guts are home to a multitude of microbes that perform vital functions, from aiding digestion to breaking down toxins and fending off parasites. "A healthy gut microbiota makes bees more resilient to threats such as pathogens and climate change," says KAUST research scientist Ramona Marasco, "highlighting the need to understand how different microbes help their host."

Extensive research into the microbiome ...

Some 42% of patients attending a dedicated diabetes clinic have signs of established chronic kidney disease, the first detailed research of its kind in Ireland has revealed.

The study was carried out by academics at NUI Galway and clinicians at University Hospital Galway Diabetes Centre and involved more than 4,500 patients in the west of Ireland.

The findings suggest that, despite careful medical management, a relatively high proportion of people with diabetes in Ireland are developing chronic kidney disease over time and are at risk of kidney failure and other complications of poor kidney function.

Diabetes ...

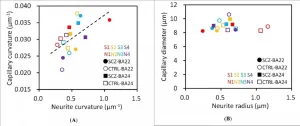

Drs. Itokawa, Mizutani and colleagues performed microtomography experiments the BL20XU beamline of the SPring-8 synchrotron radiation facility and found that brain capillary structures show a correlation with their neuron structures.

Brain blood vessels constitute a micrometer-scale vascular network responsible for supply of oxygen and nutrition. In this study, we analyzed cerebral tissues of the anterior cingulate cortex and superior temporal gyrus of schizophrenia cases and age/gender-matched controls by using synchrotron radiation microtomography or micro-CT in order to examine the three-dimensional structure of cerebral vessels.

All post-mortem human cerebral tissues were collected ...

A new species of large prehistoric croc that roamed south-east Queensland's waterways millions of years ago has been documented by University of Queensland researchers.

PhD candidate Jorgo Ristevski, from UQ's School of Biological Sciences, led the team that named the species Gunggamarandu maunala after analysing a partial skull unearthed in the Darling Downs in the nineteenth century.

"This is one of the largest crocs to have ever inhabited Australia," Mr Ristevski said.

"At the moment it's difficult to estimate the exact overall size of Gunggamarandu since all we have is the back of the skull - but it was big.

"We estimate the skull would have been at least 80 centimetres long, and based on comparisons with living crocs, this indicates a total ...

Summer picnics and barbecues are only a few weeks away! As excited as you are to indulge this summer, Escherichia coli bacteria are eager to feast on the all-you-can-eat buffet they are about to experience in your gut.

However, something unexpected will occur as E. coli cells end their journey through your digestive tract. Without warning, they will find themselves swimming in your toilet bowl, clinging to the last bits of nutrients attached to their bodies. How do these tiny organisms adapt to survive sudden starvation? Scientists at Washington University in St. Louis wondered.

Close examination of nutrient-deprived E. coli ...