Harmful protein waste in the muscle

Study clarifies cause of a rare genetic muscle disease

2021-06-14

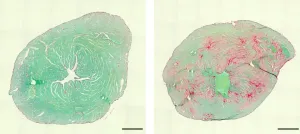

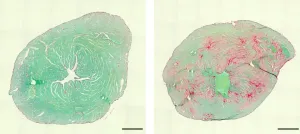

(Press-News.org) An international team of researchers led by the University of Bonn (Germany) has identified the cause of a rare, severe muscle disease. According to these findings, a single spontaneously occurring mutation results in the muscle cells no longer being able to correctly break down defective proteins. As a result, the cells perish. The condition causes severe heart failure in children, accompanied by skeletal and respiratory muscle damage. Those affected rarely live beyond the age of 20. The study also highlights experimental approaches for potential treatment. Whether this hope will be fulfilled, however, will only become clear in a few years. The results are published in the journal Nature Communications.

Anyone who has ever snapped a spoke on their bike or broken down with their car knows that mechanical stresses sooner or later result in damage that needs to be repaired. This also applies to the human musculature. "With each movement, structural proteins are damaged and have to be replaced," explains adjunct professor Dr. Michael Hesse from the Institute of Physiology at the University of Bonn, who led the study together with his colleague Prof. Dr. Bernd Fleischmann.

The defective molecules are normally broken down in the cell and their components are then recycled. An important role in this complex process is played by a protein called BAG3. The results of the new study show how important this is: The researchers were able to demonstrate that a single change in the genetic blueprint of BAG3 results in a fatal disease.

"The mutation causes BAG3 to form insoluble complexes with partner proteins that grow larger and larger," Hesse says. This brings the repair processes to a standstill - the muscles become less and less efficient. Moreover, toxic levels of proteins accumulate over time, eventually resulting in the death of the muscle cell. "The consequences are usually first seen in the heart," Hesse says. "There, muscle is successively replaced by scar tissue. This causes the heart's elasticity to decrease until it can barely pump blood."

Affected individuals therefore usually require a heart transplant in childhood. Even this measure only provides temporary relief, as the disease also affects the skeletal and respiratory muscles. As a result, sufferers often die at a young age.

Very rare condition, therefore little research

The lethal mutation can arise spontaneously during embryo development. Fortunately, this is a very rare occurrence: There are probably only a few hundred affected children worldwide. However, due to its rarity, the disease has received little research attention to date. "Our study now takes us a great deal further," stresses Bernd Fleischmann.

This is because the researchers have succeeded for the first time in replicating the disease in mice and using the new animal model to identify its causes. This allows it to be researched better than before - also with regard to possible therapies. Maybe the effect of the mutation can at least be reduced. Humans have two versions of each gene, one from the mother and the other from the father. This means that even if one version of BAG3 mutates during embryo development, there is still a second gene that is intact.

Unfortunately, however, the defective BAG3 also clumps with its intact siblings. The mutation in one of the genes is therefore sufficient to stop the breakdown of the defective muscle proteins. However, if the mutated version could be eliminated, the repair should work again. It would also prevent the massive accumulation of proteins in the cell that eventually results in its death.

There are indeed methods to specifically inhibit the activity of individual genes. "We used one of them to treat the sick mice," explains Kathrin Graf-Riesen of the Institute of Physiology, who was responsible for most of the experiments along with Dr. Kenichi Kimura and her colleague Dr. Astrid Ooms. The animals treated in this way then showed significantly fewer symptoms. Whether this approach can be transferred to humans, however, remains the subject of further research.

INFORMATION:

Participating institutions:

In addition to the Institute of Physiology I, the Institute for Cell Biology of the University of Bonn and the Clinic for Cardiac Surgery of the University Hospital Bonn were involved in the study. The partners also include Forschungszentrum Jülich, the Universities of Münster, Freiburg and Cologne, as well as Stanford University in the USA and the University of Tsukuba in Japan.

Publication: Kenichi Kimura et al: Overexpression of human BAG3P209L in mice causes restrictive cardiomyopathy. Nature Communications, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23858-7

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-14

A funny thing happened on the way to discovering how zinc impacts kidney stones - two different theories emerged, each contradicting the other. One: Zinc stops the growth of the calcium oxalate crystals that make up the stones; and two: It alters the surfaces of crystals which encourages further growth. Now it can be told - both theories are correct as reported in the America Chemical Society journal Crystal Growth & Design by Jeffrey Rimer, Abraham E. Dukler Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the University of Houston, who conducted the first study to offer some resolution to the differing hypotheses.

"What we see with zinc is something ...

2021-06-14

Our ability to confront global crises, from pandemics to climate change, depends on how we interact and share information.

Social media and other forms of communication technology restructure these interactions in ways that have consequences. Unfortunately, we have little insight into whether these changes will bring about a healthy, sustainable and equitable world. As a result, researchers now say that the study of collective behavior must rise to a "crisis discipline," just like medicine, conservation and climate science have done, according to a new paper published June 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...

2021-06-14

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) -- Scientists at UC Santa Barbara, University of Southern California (USC), and the biotechnology company Regenerative Patch Technologies LLC (RPT) have reported new methodology for preservation of RPT's stem cell-based therapy for age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The new research, recently published in Scientific Reports, optimizes the conditions to cryopreserve, or freeze, an implant consisting of a single layer of ocular cells generated from human embryonic stem cells supported by a flexible scaffold about 3x6 mm in size. ...

2021-06-14

When lithium ions flow in and out of a battery electrode during charging and discharging, a tiny bit of oxygen seeps out and the battery's voltage - a measure of how much energy it delivers - fades an equally tiny bit. The losses mount over time, and can eventually sap the battery's energy storage capacity by 10-15%.

Now researchers have measured this super-slow process with unprecedented detail, showing how the holes, or vacancies, left by escaping oxygen atoms change the electrode's structure and chemistry and gradually reduce how much energy it can store.

The results contradict some of the assumptions scientists had made about this process and could suggest new ways of engineering electrodes to prevent it.

The research team from the Department of Energy's ...

2021-06-14

MISSOULA - Those in love with the outdoors can spend their entire lives chasing that perfect campsite. New University of Montana research suggests what they are trying to find.

Will Rice, a UM assistant professor of outdoor recreation and wildland management, used big data to study the 179 extremely popular campsites of Watchman Campground in Utah's Zion National Park. Campers use an online system to reserve a wide variety of sites with different amenities, and people book the sites an average of 51 to 142 days in advance, providing hard data about demand.

Along with colleague Soyoung Park of Florida Atlantic University, Rice sifted through nearly 23,000 reservations. The researchers found that price and availability of electricity were the largest drivers of demand. Proximity ...

2021-06-14

Albeit very small, with a carapace width of only 3 cm, the Atlantic mangrove fiddler crab Leptuca thayeri can be a great help to scientists seeking to understand more about the effects of global climate change. In a study published in the journal Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, Brazilian researchers supported by São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP show how the ocean warming and acidification forecast by the end of the century could affect the lifecycle of these crustaceans.

Embryos of L. thayeri were exposed to a temperature rise of 4 °C and a pH reduction of 0.7 against the average for their habitat, growing faster as a result. However, a larger number of ...

2021-06-14

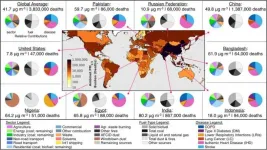

An interdisciplinary group of researchers from across the globe has comprehensively examined the sources and health effects of air pollution -- not just on a global scale, but also individually for more than 200 countries.

They found that worldwide, more than one million deaths were attributable to the burning of fossil fuels in 2017. More than half of those deaths were attributable to coal.

Findings and access to their data, which have been made public, were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Pollution is at once a global crisis and a devastatingly personal problem. It is analyzed by satellites, but PM2.5 -- tiny particles that can infiltrate a person's lungs -- can also sicken a person who cooks dinner nightly on a cookstove.

"PM2.5 ...

2021-06-14

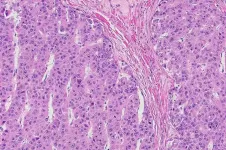

Treatment options for a deadly liver cancer, fibrolamellar carcinoma, are severely lacking. Drugs that work on other liver cancers are not effective, and although progress has been made in identifying the specific genes involved in driving the growth of fibrolamellar tumors, these findings have yet to translate into any treatment. For now, surgery is the only option for those affected--mostly children and young adults with no prior liver conditions.

Sanford M. Simon and his group understood that patients dying of fibrolamellar could not afford to wait. "There are people who need therapy now," he says. So his group threw the kitchen sink at the problem and tested over 5,000 compounds, either already approved for other clinical uses or in clinical ...

2021-06-14

DALLAS - June 14, 2021 - Overweight cancer patients receiving immunotherapy treatments live more than twice as long as lighter patients, but only when dosing is weight-based, according to a study by cancer researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

The findings, published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, run counter to current practice trends, which favor fixed dosing, in which patients are given the same dose regardless of weight. The study included data on nearly 300 patients with melanoma, lung, kidney, and head and neck cancers ...

2021-06-14

Leesburg, VA, June 14, 2021--According to ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), high-dose intranodal lymphangiography (INL) with ethiodized oil is a safe and effective procedure for treating high-output postsurgical chylothorax with chest tube removal in 83% of patients.

"To our knowledge," wrote corresponding author Geert Maleux of University Hospitals in Leuven, Belgium, "no data are available on the safety or potential beneficial effect of injecting higher doses of ethiodized oil to treat patients with refractory postoperative chylothorax."

All 18 patients (mean, 67 years; range, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Harmful protein waste in the muscle

Study clarifies cause of a rare genetic muscle disease