(Press-News.org) State-of-the-art video microscopy has enabled researchers at WEHI, Australia, to see the molecular details of how malaria parasites invade red blood cells - a key step in the disease.

The researchers used a custom-built lattice light sheet microscope - the first in Australia - to capture high-resolution videos of individual parasites invading red blood cells, and visualise the molecular and cellular changes that occur throughout this process. The research has provided critical new information about malaria parasite biology that may have applications for the development of much-needed new antimalarial medicines.

The research, which was published today in Nature Communications, was led by Ms Cindy Evelyn, Dr Niall Geoghegan, Dr Lachlan Whitehead, Professor Alan Cowman and Dr Kelly Rogers.

At a glance

An advanced microscopy platform, called lattice light sheet microscopy, has been used to obtain detailed, real-time videos of the malaria parasite invading red blood cells.

The research has revealed key steps in the parasite invasion process, which is a critical point of the malaria life-cycle and underpins many symptoms of malaria.

The team's discoveries could advance the development of much-needed new antimalarial medicines.

Focusing on a deadly parasite

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease that kills around 400,000 people globally each year. Many of the serious symptoms of malaria occur because of the invasion and growth of the Plasmodium parasite in an infected person's red blood cells, said Dr Rogers, who is the head of WEHI's Centre for Dynamic Imaging.

"Understanding in better detail exactly how the parasite invades red blood cells may reveal new ways to stop this stage of the parasite life cycle, potentially leading to much-needed new therapies," she said.

"We used microscopy - specifically a state-of-the-art approach, lattice light sheet microscopy (LLSM) - to follow the intricate cellular and molecular changes that occur when the malaria parasite invades red blood cells. We captured the first ever high-resolution, real time and dynamic views of the parasite in action."

Ms Evelyn, who began the research as an Honours student, said the research revealed many previously unrecognised aspects of parasite invasion.

"The videos we recorded showed the 'push and pull' interactions as the parasite landed on the red blood cell, and then entered the cell in an enclosed chamber - called a vacuole - where it grew and multiplied.There has long been contention in the field about whether the vacuole is derived from the parasite or the host cell. Our research resolved this question, revealing it was created from the red blood cell's membrane," she said.

Most antimalarial therapies and vaccines target the initial binding of malaria to red blood cells.

"By visualising these processes in more detail, our research may contribute in several ways to the development of new antimalarial therapies. For example, now that we know that the parasite vacuole relies on components of the red blood cell membrane, it might be possible to target these components with medicines to disrupt the parasite life cycle. This host-directed approach could be one way to bypass the malaria parasite's propensity to rapidly develop drug resistance," Dr Rogers said.

"LLSM may also have applications for observing the specific steps of parasite invasion that are blocked by potential new drugs - an area we are now very interested in pursuing."

New views of cells

LLSM is an advanced imaging technology that enables researchers to visualise cells and organs in unprecedented detail and in real time. Dr Geoghegan said LLSM had changed how cells could be studied.

"In the past, the choice of microscope for an experiment had to be a compromise between capturing a lower resolution video, which revealed dynamic processes like shape changes or movement, and capturing much higher-definition still images, which provided much more detail about how the cells and molecules are functioning," he said.

"LLSM allows us to obtain high-resolution videos of cells, which has been a game-changer for many fields of biological research.

We custom built a LLSM at WEHI - the first version of this technology in Australia. This groundbreaking microscopy has enabled us to progress multiple areas of research, including this malaria study. To achieve this, we brought together a multidisciplinary team with expertise in physics, engineering and biology - and the results of this current study have vindicated our approach."

The research was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, an EMBO Long Term Fellowship, a Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship and the Victorian Government.

INFORMATION:

Makeup wearers may be absorbing and ingesting potentially toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), according to a new study published today in Environmental Science & Technology Letters. The researchers found high fluorine levels--indicating the probable presence of PFAS--in most waterproof mascara, liquid lipsticks, and foundations tested. Some of the products with the highest fluorine levels underwent further analysis and were all confirmed to contain at least four PFAS of concern. The majority of products with high fluorine, including those ...

Many cosmetics sold in the United States and Canada likely contain high levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a potentially toxic class of chemicals linked to a number of serious health conditions, according to new research from the University of Notre Dame.

Scientists tested more than 200 cosmetics including concealers, foundations, eye and eyebrow products and various lip products. According to the study, 56 percent of foundations and eye products, 48 percent of lip products and 47 percent of mascaras tested were found to contain high levels of fluorine, which is an indicator of PFAS use in ...

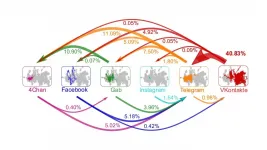

WASHINGTON (June 15, 2021)--Malicious COVID-19 online content -- including racist content, disinformation and misinformation -- thrives and spreads online by bypassing the moderation efforts of individual social media platforms, according to new research published in the journal END ...

More than 50 species of tree snail in the South Pacific Society Islands were wiped out following the introduction of an alien predatory snail in the 1970s, but the white-shelled Partula hyalina survived.

Now, thanks to a collaboration between University of Michigan biologists and engineers with the world's smallest computer, scientists understand why: P. hyalina can tolerate more sunlight than its predator, so it was able to persist in sunlit forest edge habitats.

"We were able to get data that nobody had been able to obtain," said David Blaauw, the Kensall D. Wise Collegiate Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. "And ...

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA (JUNE 15, 2021). In this longitudinal study, researchers from Wake Forest School of Medicine and the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas, Texas, examined the frequency and severity of head impacts experienced by youth football players and how exposure to head impacts changes from one year to the next in returning players. The researchers then compared the resulting data with findings on neuroimaging studies obtained over consecutive years in the same athletes. The comparison demonstrated a significant positive association between changes in head impact exposure (HIE) metrics and changes in abnormal findings on brain imaging studies. ...

A new therapy prompts immune defense cells to swallow misshapen proteins, amyloid beta plaques and tau tangles, whose buildup is known to kill nearby brain cells as part of Alzheimer's disease, a new study shows.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the investigation showed that elderly monkeys had up to 59 percent fewer plaque deposits in their brains after treatment with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG ODN), compared with untreated animals. These amyloid beta plaques are protein fragments that clump together and clog the junctions between nerve cells (neurons).

Brains of treated animals also had a ...

When young adults are more interested in socializing and casually dating, they tend to drink more alcohol, according to a new paper led by a Washington State University professor.

On the other hand, scientists found that when young adults are in serious relationships, are not interested in dating or place less importance on friendship, their alcohol use was significantly lower.

Published June 15 in the journal Substance Use & Misuse, the study included more than 700 people in the Seattle area aged 18-25 who filled out surveys every month for two years. The study used a community sample that was not limited to college students.

"Young adults shift so much in terms of social relationships ...

Nearly one in four teachers may leave their job by the end of the current (2020-'21) school year, compared with one in six who were likely to leave prior to the pandemic, according to a new RAND Corporation survey. Teachers who identified as Black or African American were particularly likely to consider leaving.

U.S. public-school teachers surveyed in January and February 2021 reported they are almost twice as likely to experience frequent job-related stress as the general employed adult population and almost three times as likely to experience depressive symptoms as the general adult population.

These results suggest potential immediate and long-term threats to the teacher supply.

"Teacher stress was a concern prior ...

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - June 15, 2021 - With preseason football training on the horizon, a new study shows that head impacts experienced during practice are associated with changes in brain imaging of young players over multiple seasons.

The research, conducted by scientists at Wake Forest School of Medicine and the University of Texas Southwestern, is published in the June 15 issue of the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics.

"Although we need more studies to fully understand what the measured changes mean, from a public health perspective, it is motivation to further reduce head impact drills used during practice in youth football," said the study's corresponding author Jill Urban, Ph.D., assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Wake Forest ...

In the heart of their Antarctic habitat, krill populations are projected to decline about 30% this century due to widespread negative effects from human-driven climate change. However, these effects on this small but significant species will be largely indistinguishable from natural variability in the region's climate until late in the 21st century, finds new University of Colorado Boulder research.

Published today in Frontiers in Marine Science, the study has important implications for not only the local food web, but for the largest commercial fishery in the Southern Ocean: A booming ...