(Press-News.org) An algorithm can predict when narwhals hunt - a task once nearly impossible to gain insight into. Mathematicians and computer scientists at the University of Copenhagen, together with marine biologists in Greenland, have made progress in gathering knowledge about this enigmatic Arctic whale at a time when climate change is pressuring them.

The small whale, known for its distinctively spiraled tusk, is under mounting pressure due to warming waters and the subsequent increase in Arctic shipping traffic. To better care for narwhals, we need to learn more about their foraging behaviour - and how these may change as a result of human disturbances and global warming. Biologists know almost nothing about this. Because narwhals live in isolated Arctic regions and hunt at depths of up to 1,000 meters, it is very difficult - sometimes impossible - to gain any insight whatsoever.

Ironically, artificial intelligence may be the answer to the mystery of their natural behaviours. An interdisciplinary collaboration between mathematicians, computer scientists and marine biologists from the University of Copenhagen and the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources demonstrates that algorithms can be used to map the foraging behavior of this enigmatic whale.

"We have shown that our algorithm can actually predict that when narwhals emit certain sounds, they are hunting prey. This opens up entirely new insights into the life of narwhals," explains Susanne Ditlevsen, a professor at UCPH's Department of Mathematical Sciences who has helped marine biologists in Greenland with the processing of data for several years.

"It is crucial to gain more insight into where and when narwhals hunt for food as sea ice recedes. If they are disturbed by shipping traffic, it matters whether this is in the middle of an important foraging area. Finding out however, is incredibly difficult. Here, artificial intelligence seems to be able to make a huge difference and to a great extent, provide us with knowledge that could not otherwise have been obtained," says cetacean researcher Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen, a professor at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and adjunct professor at the University of Copenhagen. He adds:

"In a situation where narwhals are in deep water, in the middle of the Bay of Baffin during December, we currently have no way of finding out where or when they are foraging. Here, artificial intelligence seems to be the way forward."

Algorithm maps clicks and buzzes

Until now, the best way to learn about the hunting patterns of narwhals has been to collect acoustic data using measuring instruments attached to their bodies. Like bats, narwhals orient themselves using echolocation. By making clicking sounds, they explore their environment and orient themselves. As they begin to hunt, these clicks shorten in interval to become buzzing.

While the buzzing sounds are therefore interesting to researchers, it is impossible to collect acoustic data in many places. Furthermore, recording these sounds is highly data-intensive and time consuming to analyze manually.

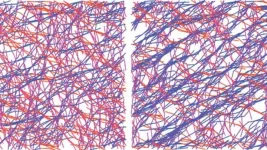

As a result, the researchers set out to investigate whether, by using artificial intelligence, they could find a pattern in the way whales move and the buzzes they emit. In the future, this would make it possible for them to rely only on measurements of animal movements using an accelerometer, a simple to use technology familiar to us from our smartphones.

"The major challenge was that these whales have very complex movement patterns, which can be tough to analyze. This becomes possible only with the use of deep learning, which could learn to recognize both the various swimming patterns of whales as well as their buzzing sounds. The algorithm then discovered connections between the two," explains Assistant Professor Raghavendra Selvan of the Department of Computer Science.

The researchers trained the algorithm using large quantities of data collected from five narwhals in Scoresby Sound fjord in East Greenland.

Now, the researchers hope to add to the algorithm by characterizing different types of buzzing sounds in order to identify the precise buzzing sounds that lead to a catch. This can be achieved by collecting data in which biologists give whales a temperature pill that detects temperature drops in their stomachs as they consume cold fish or squid.

INFORMATION:

ABOUT THE STUDY:

The researchers collected data from instruments attached to the backs of five narwhals in Scoresby Sund fjord in East Greenland.

The instruments tagged to the narwhals fell off their backs automatically after 5-8 days, after which local fishermen retrieved them from the water.

The research was conducted by M?nh C??ng Ngô (lead author) and Susanne Ditlevsen of the University of Copenhagen's Department of Mathematical Sciences, Raghavendra Selvan of the University of Copenhagen's Department of Computer Science and Outi Tervo and Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen from the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.

The research results have just been published in the scientific journal Ecological Informatics: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1574954121000662

Narwhals are widespread in the Atlantic Arctic, including along the east and west coasts of Greenland. Worldwide, the narwhal is not categorised as an endangered species. Locally, several stocks are in decline. The IUCN estimates that there are approximately 123,000 adult narwhals worldwide.

For many of us, our smartphone has become our ever-present companion and is usually far more than just a phone. Thanks to the constant availability of online content as well as our reachability through messenger services and social networks via our smartphone, this everyday object's potential to distract us is high - at work too. This is why many employers view the use of smartphones during work time with suspicion, and countermeasures taken range from asking staff to refrain voluntarily from using them to banning smartphones in the workplace through an internal agreement. But do such measures actually work and, if so, how?

This is the ...

DURHAM, N.C. - Special diets, exercise programs, supplements and vitamins -- everywhere we look there is something supposed to help us live longer. Maybe those work: human average life expectancy has gone from a meager 40-ish years to a whopping 70-something since 1850. Does this mean we are slowing down death?

A new study comparing data from nine human populations and 30 populations of non-human primates says that we are probably not cheating the reaper. The researchers say the increase in human life expectancy is more likely the statistical outcome of improved survival for children and young adults, not slowing the aging clock.

"Populations get older mostly because more individuals get through those early stages of life," ...

In the majority of insects, metamorphosis fosters completely different looking larval and adult stages. For example, adult butterflies are completely different from their larval counterparts, termed caterpillars. This "decoupling" of life stages is thought to allow for adaptation to different environments. Researchers of the University of Bonn now falsified this text book knowledge of evolutionary theory for stoneflies. They found that the ecology of the larvae largely determines the morphology of the adults by investigating 219 earwig and stonefly species at high-resolution particle accelerators. The study has ...

Osteoporosis researchers at the UVA School of Medicine have taken a new approach to understanding how our genes determine the strength of our bones, allowing them to identify several genes not previously known to influence bone density and, ultimately, our risk of fracture.

The work offers important insights into osteoporosis, a condition that affects 10 million Americans, and it provides scientists potential new targets in their battle against the brittle-bone disease.

Importantly, the approach uses a newly created population of laboratory mice that allows researchers to identify relevant genes and overcome limitations of human studies. Identifying such genes has been very difficult but is key to using genetic discoveries to improve ...

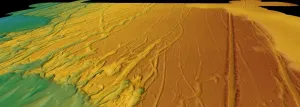

Woods Hole, MA (June 16, 2021) -- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) climate modeler Dr. Alan Condron and United States Geological Survey (USGS) research geologist Dr. Jenna Hill have found evidence that massive icebergs from roughly 31,000 years ago drifted more than 5000km (> 3,000 miles) along the eastern United States coast from Northeast Canada all the way to southern Florida. These findings were published today in Nature Communications.

Using high resolution seafloor mapping, radiocarbon dating and a new iceberg model, the team analyzed about 700 iceberg scours ("plow marks" on the seafloor left behind by the bottom parts of icebergs dragging through marine sediment ) from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to the Florida Keys. ...

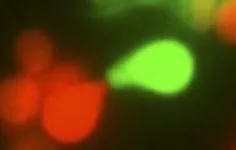

Researchers from the Max-Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology have discovered a surprising asymmetry in the mating behavior of unicellular yeast that emerges solely from molecular differences in pheromone signaling. Their results, published in the current issue of "Science Advances", might shed new light on the evolutionary origins of sexual dimorphism in higher eukaryotes.

Resemblant of higher organisms, yeast gametes communicate during the mating process by secreting and sensing sexual pheromones. However, in contrast to higher eukaryotes, budding yeast is isogamous: seen through a microscope, gametes of both mating types ("sexes"), MATa and MATα, look exactly the same. Since anisogamy -- difference in size between male and female gametes --was ...

HOUSTON ? The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center's Research Highlights provides a glimpse into recently published studies in basic, translational and clinical cancer research from MD Anderson experts. Current advances include a new combination therapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a greater understanding of persistent conditions after AML remission, the discovery of a universal biomarker for exosomes, the identification of a tumor suppressor gene in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and characterization of a new target to treat Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infections.

Utilizing combination therapy for AML

While a majority of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) respond favorably ...

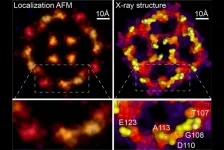

Scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine have developed a computational technique that greatly increases the resolution of atomic force microscopy, a specialized type of microscope that "feels" the atoms at a surface. The method reveals atomic-level details on proteins and other biological structures under normal physiological conditions, opening a new window on cell biology, virology and other microscopic processes.

In a study, published June 16 in Nature, the investigators describe the new technique, which is based on a strategy used to improve resolution in light microscopy.

To study proteins and other biomolecules at high resolution, investigators have long relied on two techniques: X-ray crystallography ...

A new rubber band stretches, but then snaps back into its original shape and size. Stretched again, it does the same. But what if the rubber band was made of a material that remembered how it had been stretched? Just as our bones strengthen in response to impact, medical implants or prosthetics composed of such a material could adjust to environmental pressures such as those encountered in strenuous exercise.

A research team at the University of Chicago is now exploring the properties of a material found in cells which allows cells to remember and respond to environmental pressure. In a paper published on May 14, 2021 in Soft Matter, they teased ...

PHILADELPHIA - Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that strikes nearly 5,000 people in the U.S. every year. About 10% of ALS cases are inherited or familial, often caused by an error in the C9orf72 gene. Compared to sporadic or non-familial ALS, C90rf72 patients are considered to have a more aggressive disease course. Evidence points to the immune system in disease progression in C90rf72 patients, but we know little of what players are involved. New research from the Jefferson Weinberg ALS Center identified an increased ...