(Press-News.org) Scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine have developed a computational technique that greatly increases the resolution of atomic force microscopy, a specialized type of microscope that "feels" the atoms at a surface. The method reveals atomic-level details on proteins and other biological structures under normal physiological conditions, opening a new window on cell biology, virology and other microscopic processes.

In a study, published June 16 in Nature, the investigators describe the new technique, which is based on a strategy used to improve resolution in light microscopy.

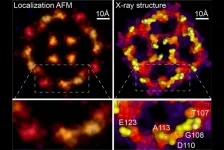

To study proteins and other biomolecules at high resolution, investigators have long relied on two techniques: X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. While both methods can determine molecular structures down to the resolution of individual atoms, they do so on molecules that are either scaffolded into crystals or frozen at ultra-cold temperatures, possibly altering them from their normal physiological shapes. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) can analyze biological molecules under normal physiological conditions, but the resulting images have been blurry and low resolution.

"Atomic force microscopy can easily resolve atoms in physics, on solid surfaces of silicates and on semiconductors, so it means that in principle the machine has the precision to do that," said senior author Dr. Simon Scheuring, professor of physiology and biophysics in anesthesiology at Weill Cornell Medicine. "The technique is a bit like if you were to take a pen and scan over the Rocky Mountains, so that you get a topographic map of the object. In reality, our pen is a needle that is sharp down to a few atoms and the objects are single protein molecules."

However, biological molecules have many small parts that wiggle, blurring their AFM images. To address that problem, Dr. Scheuring and his colleagues adapted a concept from light microscopy called super-resolution microscopy. "Theoretically it wasn't possible by optical microscopy to resolve two fluorescent molecules that were closer together than half the wavelength of the light," he said. However, by stimulating the adjacent molecules to fluoresce at different times, microscopists can analyze the spread of each molecule and pinpoint their locations with high precision.

Instead of stimulating fluorescence, Dr. Scheuring's team noted that the natural fluctuations of biological molecules recorded over the course of AFM scans yield similar spreads of positional data. First author Dr. George Heath, who was a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medicine at the time of the study and is now a faculty member at the University of Leeds, engaged in cycles of experiments and computational simulations to understand the AFM imaging process in greater detail and extract the maximum of information from the atomic interactions between tip and sample.

Using a method like super-resolution analysis, they were able to extract much higher resolution images of the moving molecules. Continuing the topographic analogy, Dr. Scheuring explained that "if the rocks (i.e., atoms) wiggle a little bit up and down, you can detect this one, then that one, and then you average all detections over time and you receive high-resolution information."

Because previous AFM studies have routinely collected the necessary data, the new technique can be applied retroactively to the blurry images the field has generated for decades. As an example, the new paper includes an analysis of an AFM scan of an aquaporin membrane protein, originally acquired during Dr. Scheuring's doctoral thesis. The reanalysis generated a much sharper image that matches X-ray crystallography structures of the molecule closely. "You basically get quasi-atomic resolution on these surfaces now," said Dr. Scheuring. To showcase the power of the method, the authors provide new high-resolution data on annexin, a protein involved in cell membrane repair, and on a proton-chloride antiporter of which they also report structural changes related to its functional.

Besides allowing researchers to study biological molecules under physiologically relevant conditions, the new method has other advantages. For example, X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy rely on averaging data from large numbers of molecules, but AFM can generate images of single molecules. "Instead of having observations of hundreds of molecules, we observe one molecule a hundred times and calculate a high-resolution map," said Dr. Scheuring.

Imaging individual molecules as they carry out their functions could open entirely new types of analysis. "Let's say you have a [viral] spike protein that's in one conformation and then it gets activated and goes into another conformation," said Dr. Scheuring. "You would in principle be able to calculate a high-resolution map from that same molecule as it transits from one conformation to the next, not from thousands of molecules in one or the other conformation." Such high-resolution single molecule data could provide more detailed information and avoid the potentially misleading results that can occur when averaging data from many molecules. Furthermore, the map might reveal new strategies for precisely redirecting or interrupting such processes.

INFORMATION:

Additional study co-authors include Drs. Ekaterina Kots, Shifra Lansky, George Khelashvili, and Harel Weinstein from the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine and Dr. Janice Robertson from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics at Washington University.

A new rubber band stretches, but then snaps back into its original shape and size. Stretched again, it does the same. But what if the rubber band was made of a material that remembered how it had been stretched? Just as our bones strengthen in response to impact, medical implants or prosthetics composed of such a material could adjust to environmental pressures such as those encountered in strenuous exercise.

A research team at the University of Chicago is now exploring the properties of a material found in cells which allows cells to remember and respond to environmental pressure. In a paper published on May 14, 2021 in Soft Matter, they teased ...

PHILADELPHIA - Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that strikes nearly 5,000 people in the U.S. every year. About 10% of ALS cases are inherited or familial, often caused by an error in the C9orf72 gene. Compared to sporadic or non-familial ALS, C90rf72 patients are considered to have a more aggressive disease course. Evidence points to the immune system in disease progression in C90rf72 patients, but we know little of what players are involved. New research from the Jefferson Weinberg ALS Center identified an increased ...

While crop yield has achieved a substantial boost from nanotechnology in recent years, alarms over the health risks posed by nanoparticles within fresh produce and grains have also increased. In particular, nanoparticles entering the soil through irrigation, fertilizers and other sources have raised concerns about whether plants absorb these minute particles enough to cause toxicity.

In a new study published online in the journal END ...

Although each organism has a unique genome, a single gene sequence, each individual has many epigenomes. An epigenome consists of chemical compounds and proteins that can bind to DNA and regulate gene action, either by activating or deactivating them or producing organ- or tissue-specific proteins. As it is a highly dynamic material, it can provide a large amount of information to shed light on the evolution of the various tissues and organs that make up the body.

Now, a team from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE), a joint centre of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and Pompeu Fabra University, has carried out the largest study to date on the regulatory ...

By repurposing common ingredients in hair conditioner, scientists have designed an inexpensive, transparent coating that can turn surfaces like windows and ceilings into glue pads to trap airborne aerosol droplets. This new strategy is described June 16 in the journal Chem.

"Facing a pandemic, we need to proactively leverage all of the different layers of defense mechanisms, including the physical barriers," says corresponding author Jiaxing Huang, a professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern University. "After all, these viruses must travel through physical space before reaching and eventually infecting people."

The ...

Small modeling errors may accumulate faster than previously expected when physicists combine multiple gravitational wave events (such as colliding black holes) to test Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, suggest researchers at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. The findings, published June 16 in the journal iScience, suggest that catalogs with as few as 10 to 30 events with a signal-to-background noise ratio of 20 (which is typical for events used in this type of test) could provide misleading deviations from general relativity, erroneously pointing to new physics where none exists. Because this is close to the size of current catalogs used to assess Einstein's ...

Human babies do even more than we thought while sleeping.

A new study from University of Iowa researchers provides further insights into the coordination that takes place between infants' brains and bodies as they sleep.

The Iowa researchers have for years studied infants' twitching movements during REM sleep and how those twitches contribute to babies' ability to coordinate their bodily movements. In this study, the scientists report that beginning around three months of age, infants see a pronounced increase in twitching during a second major stage of sleep, called quiet sleep.

"This was completely surprising and, for all we know, ...

When Betelgeuse, a bright orange star in the constellation of Orion, lost more than two-thirds of its brightness in late 2019 and early 2020, astronomers were puzzled.

What could cause such an abrupt dimming?

Now, in a new paper published Wednesday in Nature, an international team of astronomers reveal two never-before-seen images of the mysterious darkening --and an explanation. The dimming was caused by a dusty veil shading the star, which resulted from a drop in temperature on Betelgeuse's stellar surface.

Led by Miguel Montargès at the Observatoire de Paris, the new images were taken in January and March of 2020 using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope. Combined with images previously taken in ...

EMBARGOED UNTIL 11 A.M. ET WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021

MADISON, Wis. -- Quantum computers could outperform classical computers at many tasks, but only if the errors that are an inevitable part of computational tasks are isolated rather than widespread events. Now, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have found evidence that errors are correlated across an entire superconducting quantum computing chip -- highlighting a problem that must be acknowledged and addressed in the quest for fault-tolerant quantum computers.

The researchers report their findings in a study published June 16 in the journal Nature, Importantly, their work also points to mitigation strategies.

"I think people have been approaching the problem of error correction in an overly optimistic ...

It is possible to re-create a bird's song by reading only its brain activity, shows a first proof-of-concept study from the University of California San Diego. The researchers were able to reproduce the songbird's complex vocalizations down to the pitch, volume and timbre of the original.

Published June 16 in Current Biology, the study lays the foundation for building vocal prostheses for individuals who have lost the ability to speak.

"The current state of the art in communication prosthetics is implantable devices that allow you to generate textual output, writing up to 20 words per minute," said senior author Timothy Gentner, a professor of psychology and neurobiology ...