(Press-News.org) A new rubber band stretches, but then snaps back into its original shape and size. Stretched again, it does the same. But what if the rubber band was made of a material that remembered how it had been stretched? Just as our bones strengthen in response to impact, medical implants or prosthetics composed of such a material could adjust to environmental pressures such as those encountered in strenuous exercise.

A research team at the University of Chicago is now exploring the properties of a material found in cells which allows cells to remember and respond to environmental pressure. In a paper published on May 14, 2021 in Soft Matter, they teased out secrets for how it works--and how it could someday form the basis for making useful materials.

Protein strands, called actin filaments, act as bones within a cell, and a separate family of proteins called cross-linkers hold these bones together into a cellular skeleton. The study found that an optimal concentration of cross-linkers, which bind and unbind to permit the actin to rearrange under pressure, allow this skeletal scaffolding to remember and respond to past experience. This material memory is called hysteresis.

"Our findings show that the properties of actin networks can be changed by how filaments are aligned," said Danielle Scheff, a graduate student in the Department of Physics who conducted the research in the lab of Margaret Gardel, Horace B. Horton Professor of Physics and Molecular Engineering, the James Franck Institute, and the Institute of Biophysical Dynamics. "The material adapts to stress by becoming stronger."

To understand how the composition of this cellular scaffolding determines its hysteresis, Scheff mixed up a buffer containing actin, isolated from rabbit muscle, and cross-linkers, isolated from bacteria. She then applied pressure to the solution, using an instrument called a rheometer. If stretched in one direction, the cross-linkers allowed the actin filaments to rearrange, strengthening against subsequent pressure in the same direction.

To see how hysteresis depended on the solution's consistency, she mixed different concentrations of cross-linkers into the buffer.

Surprisingly, these experiments indicated that hysteresis was most pronounced at an optimal cross-linker concentration; solutions exhibited increased hysteresis as she added more cross-linkers, but past this optimal point, the effect again became less pronounced.

"I remember being in lab the first time I plotted that relationship and thinking something must be wrong, running down to the rheometer to do more experiments to double-check," Scheff said.

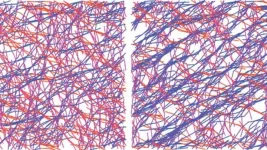

To better understand the structural changes, Steven Redford, a graduate student in Biophysical Sciences in the labs of Gardel and Aaron Dinner, Professor of Chemistry, the James Franck Institute, and the Institute for Biophysical Dynamics, created a computational simulation of the protein mixture Scheff produced in the lab. In this computational rendition, Redford wielded a more systematic control over variables than possible in the lab. By varying the stability of bonds between actin and its cross-linkers, Redford showed that unbinding allows actin filaments to rearrange under pressure, aligning with the applied strain, while binding stabilizes the new alignment, providing the tissue a 'memory' of this pressure. Together, these simulations demonstrated that impermanent connections between the proteins enable hysteresis.

"People think of cells as very complicated, with a lot of chemical feedback. But this is a stripped-down system where you can really understand what is possible," said Gardel.

The team expects these findings, established in a material isolated from biological systems, to generalize to other materials. For example, using impermanent cross-linkers to bind polymer filaments could allow them to rearrange as actin filaments do, and thus produce synthetic materials capable of hysteresis.

"If you understand how natural materials adapt, you can carry it over to synthetic materials," said Dinner.

INFORMATION:

The collaboration between the Gardel and Dinner labs reflects broader efforts to understand adaptive properties of materials at UChicago's Materials Research Science and Engineering Center and the James Franck Institute.

Citation: Scheff DR, et al., (2021) Actin filament alignment causes mechanical hysteresis in cross-linked networks. Soft Matter. DOI: 10.1039/d1sm00412c

PHILADELPHIA - Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that strikes nearly 5,000 people in the U.S. every year. About 10% of ALS cases are inherited or familial, often caused by an error in the C9orf72 gene. Compared to sporadic or non-familial ALS, C90rf72 patients are considered to have a more aggressive disease course. Evidence points to the immune system in disease progression in C90rf72 patients, but we know little of what players are involved. New research from the Jefferson Weinberg ALS Center identified an increased ...

While crop yield has achieved a substantial boost from nanotechnology in recent years, alarms over the health risks posed by nanoparticles within fresh produce and grains have also increased. In particular, nanoparticles entering the soil through irrigation, fertilizers and other sources have raised concerns about whether plants absorb these minute particles enough to cause toxicity.

In a new study published online in the journal END ...

Although each organism has a unique genome, a single gene sequence, each individual has many epigenomes. An epigenome consists of chemical compounds and proteins that can bind to DNA and regulate gene action, either by activating or deactivating them or producing organ- or tissue-specific proteins. As it is a highly dynamic material, it can provide a large amount of information to shed light on the evolution of the various tissues and organs that make up the body.

Now, a team from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE), a joint centre of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and Pompeu Fabra University, has carried out the largest study to date on the regulatory ...

By repurposing common ingredients in hair conditioner, scientists have designed an inexpensive, transparent coating that can turn surfaces like windows and ceilings into glue pads to trap airborne aerosol droplets. This new strategy is described June 16 in the journal Chem.

"Facing a pandemic, we need to proactively leverage all of the different layers of defense mechanisms, including the physical barriers," says corresponding author Jiaxing Huang, a professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern University. "After all, these viruses must travel through physical space before reaching and eventually infecting people."

The ...

Small modeling errors may accumulate faster than previously expected when physicists combine multiple gravitational wave events (such as colliding black holes) to test Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, suggest researchers at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. The findings, published June 16 in the journal iScience, suggest that catalogs with as few as 10 to 30 events with a signal-to-background noise ratio of 20 (which is typical for events used in this type of test) could provide misleading deviations from general relativity, erroneously pointing to new physics where none exists. Because this is close to the size of current catalogs used to assess Einstein's ...

Human babies do even more than we thought while sleeping.

A new study from University of Iowa researchers provides further insights into the coordination that takes place between infants' brains and bodies as they sleep.

The Iowa researchers have for years studied infants' twitching movements during REM sleep and how those twitches contribute to babies' ability to coordinate their bodily movements. In this study, the scientists report that beginning around three months of age, infants see a pronounced increase in twitching during a second major stage of sleep, called quiet sleep.

"This was completely surprising and, for all we know, ...

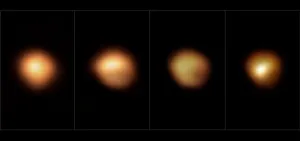

When Betelgeuse, a bright orange star in the constellation of Orion, lost more than two-thirds of its brightness in late 2019 and early 2020, astronomers were puzzled.

What could cause such an abrupt dimming?

Now, in a new paper published Wednesday in Nature, an international team of astronomers reveal two never-before-seen images of the mysterious darkening --and an explanation. The dimming was caused by a dusty veil shading the star, which resulted from a drop in temperature on Betelgeuse's stellar surface.

Led by Miguel Montargès at the Observatoire de Paris, the new images were taken in January and March of 2020 using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope. Combined with images previously taken in ...

EMBARGOED UNTIL 11 A.M. ET WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021

MADISON, Wis. -- Quantum computers could outperform classical computers at many tasks, but only if the errors that are an inevitable part of computational tasks are isolated rather than widespread events. Now, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have found evidence that errors are correlated across an entire superconducting quantum computing chip -- highlighting a problem that must be acknowledged and addressed in the quest for fault-tolerant quantum computers.

The researchers report their findings in a study published June 16 in the journal Nature, Importantly, their work also points to mitigation strategies.

"I think people have been approaching the problem of error correction in an overly optimistic ...

It is possible to re-create a bird's song by reading only its brain activity, shows a first proof-of-concept study from the University of California San Diego. The researchers were able to reproduce the songbird's complex vocalizations down to the pitch, volume and timbre of the original.

Published June 16 in Current Biology, the study lays the foundation for building vocal prostheses for individuals who have lost the ability to speak.

"The current state of the art in communication prosthetics is implantable devices that allow you to generate textual output, writing up to 20 words per minute," said senior author Timothy Gentner, a professor of psychology and neurobiology ...

When Betelgeuse, a bright orange star in the constellation of Orion, became visibly darker in late 2019 and early 2020, the astronomy community was puzzled. A team of astronomers have now published new images of the star's surface, taken using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (ESO's VLT), that clearly show how its brightness changed. The new research reveals that the star was partially concealed by a cloud of dust, a discovery that solves the mystery of the "Great Dimming" of Betelgeuse.

Betelgeuse's dip in brightness -- a change noticeable even to the ...