(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. - Special diets, exercise programs, supplements and vitamins -- everywhere we look there is something supposed to help us live longer. Maybe those work: human average life expectancy has gone from a meager 40-ish years to a whopping 70-something since 1850. Does this mean we are slowing down death?

A new study comparing data from nine human populations and 30 populations of non-human primates says that we are probably not cheating the reaper. The researchers say the increase in human life expectancy is more likely the statistical outcome of improved survival for children and young adults, not slowing the aging clock.

"Populations get older mostly because more individuals get through those early stages of life," said Susan Alberts, professor of Biology and Evolutionary Anthropology at Duke University and senior author of the paper. "Early life used to be so risky for humans, whereas now we prevent most early deaths."

The research team, comprising scientists from 14 different countries, analyzed patterns of births and deaths in the 39 populations, looking at the relationship between life expectancy and lifespan equality.

Lifespan equality tell us how much the age of death varies in a population. If everyone tends to die at around the same age -- for instance, if almost everyone can expect to live a long life and die in their 70s or 80s -- lifespan equality is very high. If death could happen at any age -- because of disease, for example -- lifespan equality is very low.

In humans, lifespan equality is closely related to life expectancy: people from populations that live longer also tend to die at a similarly old age, while populations with shorter life-expectancies tend to die at a wider range of ages.

To understand if this pattern is uniquely human, the researchers turned to our closest cousins: non-human primates. What they found is that the tight relationship between life expectancy and lifespan equality is widespread among primates as well as humans. But why?

In most mammals, risk of death is high at very young ages and relatively low at adulthood, then it increases again after the onset of aging. Could higher life-expectancy be due to individuals ageing slower and living longer?

The primate populations tell us that the answer is probably no. The main sources of variation in the average age of death in different primate populations were infant, juvenile and young adult deaths. In other words, life expectancy and lifespan equality are not driven by the rate at which individuals senesce and become old, but by how many kids and young adults die for reasons unrelated to old age.

Using mathematical modeling, the researchers also found that small changes in the rate of ageing would drastically alter the relationship between life expectancy and lifespan equality. Changes in the parameters representing early deaths, on the other hand, led to variations very similar to what was observed.

"When we change the parameters representing early deaths, we can explain almost all of the variation among populations, for all of these species," said Alberts. "Changes in the onset of aging and rate of ageing do not explain this variation."

These results support the 'invariant rate of ageing' hypothesis.

"The rate of ageing is relatively fixed for a species," said Alberts. "That's why the relationship between life expectancy and lifespan equality is so tight within each species."

The researchers point out that there is some individual variation within species in the rate of ageing and on the onset of senescence, but that this variation is contained to a fairly narrow range, unlike death rates at younger ages.

"We can't slow down the rate at which we're going to age," Alberts said. "What we can do is prevent those babies from dying."

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01AG031719), with additional support provided by the Max Planck Institute of Demographic Research and the Duke University Population Research Institute.

INFORMATION:

CITATION: "The Long Lives of Primates and the 'Invariant Rate of Ageing' Hypothesis," F. Colchero, J.M. Aburto, E.A. Archie, C. Boesch, T. Breuer, F.A. Campos, A. Collins, D.A. Conde, M. Cords, C. Crockford, M.E. Thompson, L.M. Fedigan, C. Fichtel, M. Groenenberg, C. Hobaiter, P.M. Kappeler, R.R. Lawler, R.J. Lewis, Z.P. Machanda, M.L. Manguette, M.N. Muller, C. Packer, R.J. Parnell, S. Perry, A.E. Pusey, M.M. Robbins, R.M. Seyfarth, J.B. Silk, J. Staerk, T.S. Stoinski, E.J. Stokes, K.B. Strier, S.C. Strum, J. Tung, F. Villavicencio, R.M. Wittig, R.W. Wrangham, K. Zuberbühler, J.W. Vaupel, S.C. Alberts. Nature Communications, June 16, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-23894-3

In the majority of insects, metamorphosis fosters completely different looking larval and adult stages. For example, adult butterflies are completely different from their larval counterparts, termed caterpillars. This "decoupling" of life stages is thought to allow for adaptation to different environments. Researchers of the University of Bonn now falsified this text book knowledge of evolutionary theory for stoneflies. They found that the ecology of the larvae largely determines the morphology of the adults by investigating 219 earwig and stonefly species at high-resolution particle accelerators. The study has ...

Osteoporosis researchers at the UVA School of Medicine have taken a new approach to understanding how our genes determine the strength of our bones, allowing them to identify several genes not previously known to influence bone density and, ultimately, our risk of fracture.

The work offers important insights into osteoporosis, a condition that affects 10 million Americans, and it provides scientists potential new targets in their battle against the brittle-bone disease.

Importantly, the approach uses a newly created population of laboratory mice that allows researchers to identify relevant genes and overcome limitations of human studies. Identifying such genes has been very difficult but is key to using genetic discoveries to improve ...

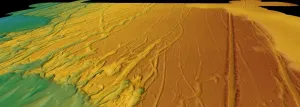

Woods Hole, MA (June 16, 2021) -- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) climate modeler Dr. Alan Condron and United States Geological Survey (USGS) research geologist Dr. Jenna Hill have found evidence that massive icebergs from roughly 31,000 years ago drifted more than 5000km (> 3,000 miles) along the eastern United States coast from Northeast Canada all the way to southern Florida. These findings were published today in Nature Communications.

Using high resolution seafloor mapping, radiocarbon dating and a new iceberg model, the team analyzed about 700 iceberg scours ("plow marks" on the seafloor left behind by the bottom parts of icebergs dragging through marine sediment ) from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to the Florida Keys. ...

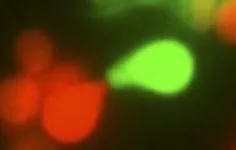

Researchers from the Max-Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology have discovered a surprising asymmetry in the mating behavior of unicellular yeast that emerges solely from molecular differences in pheromone signaling. Their results, published in the current issue of "Science Advances", might shed new light on the evolutionary origins of sexual dimorphism in higher eukaryotes.

Resemblant of higher organisms, yeast gametes communicate during the mating process by secreting and sensing sexual pheromones. However, in contrast to higher eukaryotes, budding yeast is isogamous: seen through a microscope, gametes of both mating types ("sexes"), MATa and MATα, look exactly the same. Since anisogamy -- difference in size between male and female gametes --was ...

HOUSTON ? The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center's Research Highlights provides a glimpse into recently published studies in basic, translational and clinical cancer research from MD Anderson experts. Current advances include a new combination therapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a greater understanding of persistent conditions after AML remission, the discovery of a universal biomarker for exosomes, the identification of a tumor suppressor gene in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and characterization of a new target to treat Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infections.

Utilizing combination therapy for AML

While a majority of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) respond favorably ...

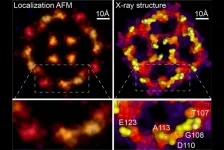

Scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine have developed a computational technique that greatly increases the resolution of atomic force microscopy, a specialized type of microscope that "feels" the atoms at a surface. The method reveals atomic-level details on proteins and other biological structures under normal physiological conditions, opening a new window on cell biology, virology and other microscopic processes.

In a study, published June 16 in Nature, the investigators describe the new technique, which is based on a strategy used to improve resolution in light microscopy.

To study proteins and other biomolecules at high resolution, investigators have long relied on two techniques: X-ray crystallography ...

A new rubber band stretches, but then snaps back into its original shape and size. Stretched again, it does the same. But what if the rubber band was made of a material that remembered how it had been stretched? Just as our bones strengthen in response to impact, medical implants or prosthetics composed of such a material could adjust to environmental pressures such as those encountered in strenuous exercise.

A research team at the University of Chicago is now exploring the properties of a material found in cells which allows cells to remember and respond to environmental pressure. In a paper published on May 14, 2021 in Soft Matter, they teased ...

PHILADELPHIA - Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that strikes nearly 5,000 people in the U.S. every year. About 10% of ALS cases are inherited or familial, often caused by an error in the C9orf72 gene. Compared to sporadic or non-familial ALS, C90rf72 patients are considered to have a more aggressive disease course. Evidence points to the immune system in disease progression in C90rf72 patients, but we know little of what players are involved. New research from the Jefferson Weinberg ALS Center identified an increased ...

While crop yield has achieved a substantial boost from nanotechnology in recent years, alarms over the health risks posed by nanoparticles within fresh produce and grains have also increased. In particular, nanoparticles entering the soil through irrigation, fertilizers and other sources have raised concerns about whether plants absorb these minute particles enough to cause toxicity.

In a new study published online in the journal END ...

Although each organism has a unique genome, a single gene sequence, each individual has many epigenomes. An epigenome consists of chemical compounds and proteins that can bind to DNA and regulate gene action, either by activating or deactivating them or producing organ- or tissue-specific proteins. As it is a highly dynamic material, it can provide a large amount of information to shed light on the evolution of the various tissues and organs that make up the body.

Now, a team from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE), a joint centre of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and Pompeu Fabra University, has carried out the largest study to date on the regulatory ...