(Press-News.org) SINGAPORE, 17 June 2021 - New details on the structure and function of a transport protein could help researchers develop drugs for neurological diseases that are better able to cross the blood-brain barrier. The findings were published in the journal Nature by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Duke-NUS Medical School, Weill Cornell Medicine and colleagues.

Omega-3 fatty acids, like docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are important for brain and eye development. They are derived mainly from dietary sources and converted by the liver into a lysolipid called lyso-phosphatidyl-choline (LPC) in order to cross from the blood into the brain and retina via the blood-brain and blood-retina barriers, respectively. These barriers are formed by cells lining blood vessels, or endothelial cells, that tightly regulate what enters these two vital organs.

A protein called 'Major Facilitator Superfamily Domain containing 2A' (MFSD2A) is located on the membrane of these endothelial cells, and acts as a molecular gateway that allows DHA to cross these barriers. How MFSD2A mediates uptake of lysolipids carrying omega-3 fatty acids, however, remained a mystery.

"We set out to determine the structure of MFSD2A in order to understand how it transports essential omega-3 fatty acids in the form of LPC to the brain," said Dr Chua Geok Lin, a senior research fellow with the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases (CVMD) Programme, Duke-NUS, who is a co-author of the study. "This is important because MFSD2A is essential for getting omega-3 fatty acids like DHA across the blood-brain barrier."

Dr Rosemary Cater, a Simons Foundation Fellow at Columbia University's Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, and first author of the paper, explained, "If we knew what MFSD2A looked like, we could solve this mystery and use the information to design neurotherapeutics that could hijack this molecular gateway, disguised as omega-3 fatty acid lysolipids--sort of like seeing what a lock looks like in order to design a key that fits."

The collaborative study, led by Dr Filippo Mancia at Columbia University, Dr David Silver at Duke-NUS, and Dr George Khelashvili at Weill Cornell Medicine, leveraged leading experts in the field from across a number of US research institutions--namely Columbia University, Weill Cornell Medicine, the New York Structural Biology Center, University of Chicago and University of Arizona--and Duke-NUS in Singapore.

To study the structure of MFSD2A, the research team used a special type of electron microscopy, which involves cooling samples to cryogenic temperatures and viewing molecules on a sub-nanomolar scale, in combination with novel biochemical assays. This allowed them to uncover atomic-level details of the protein's structure, which were then used to inform computer simulations exploring the mechanism of how it works.

According to Dr Mancia, Associate Professor of Physiology and Cellular Biophysics at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, "It's extremely exciting to be able to view a protein's shape at such a resolution. We are talking about measurements of less than a billionth of a metre in size--and this information is critical to understand how it works at a molecular level."

"Using large-scale atomistic ensemble molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, followed by detailed analysis of the MD data with advanced methods of computational biophysics, such as Markov State Modelling, we were able to 'un-freeze' the cryo-EM structure of MFSD2A and study mechanistic details of how this transporter interacts with substrates," explained Dr Khelashvili, Assistant Professor of Physiology and Biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine. "Combined with the functional data, the computational findings shed light on the molecular mechanisms by which this atypical MFS transporter mediates uptake of single-chain phospholipids into the brain."

"Some years ago, we discovered that human mutations in the gene that codes for MFSD2A lead to microcephaly, a birth defect in which the baby's head is very small," said Dr Silver, Professor and Deputy Director of Duke-NUS' CVMD Programme. "This underscores the importance of lysolipid transport by MFSD2A."

The study is the latest to add to the growing body of knowledge first initiated by Prof Silver in 2014, when he published on the discovery of MFSD2A and its role in transporting DHA to the brain. In 2017, he co-founded Singapore-based Travecta Therapeutics with the aim of harnessing this knowledge to develop new therapeutic agents that can be selectively delivered across the blood-brain barrier by MFSD2A for treatment of diseases of the central nervous system and eyes. Travecta is currently conducting preclinical studies for several therapeutic targets with the company's lead asset for pain, TVT-004, scheduled to begin clinical trials in the next several months.

A license agreement between Duke-NUS and Travecta was facilitated by Duke-NUS' Centre for Technology and Development, under the School's Office of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, granting the company rights to commercialise the research.

"The blood-brain barrier excludes the uptake of approximately 98 per cent of drugs, limiting the treatment of neurological diseases," Prof Silver explained. "The structural information we revealed in our study can be exploited to better design neurotherapeutics that can be transported by MFSD2A."

The authors said further research is needed to uncover more details on how MFSD2A mediates transport of lysolipids across the blood-brain barrier.

INFORMATION:

New research presents over 300 new analyses of bronze objects, raising the total number to 550 in 'the archaeological fingerprint project'. This is roughly two thirds of the entire metal inventory of the early Bronze Age in southern Scandinavia. For the first time, it was possible to map the trade networks for metals and to identify changes in the supply routes, coinciding with other socio-economic changes detectable in the rich metal-dependent societies of Bronze Age southern Scandinavia.

The magnificent Bronze Age in southern Scandinavia rose from copper traded from the British Isles and Slovakia 4000 years ago. 500 ...

In a paper published in NANO, a team of researchers from Jiangnan University, China have prepared a convenient sensing platform which can detect microRNA-205 (MiR-205) with high sensitivity and excellent selectivity using TpTta-COF nanosheet and fluorescent oligonucleotide probes.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a kind of malignant cancer derived from the epithelial cells, which shows an apparent regional aggregation with a high prevalence in Southern China and Southeast Asia. With the ongoing improvement of radiotherapy technology, the therapeutic effect of NPC patients has been increased significantly. However, the easy recurrence and metastasis still cause the poor prognosis of NPC patients. Many researches indicated that ...

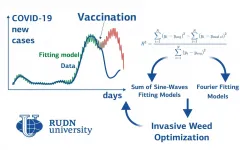

RUDN University mathematicians built a model of COVID-19 spreading based on two regression models. The mathematicians divided the countries into three groups, depending on the spreading rate and on the climatic conditions, and found a suitable mathematical approximation for each of them. Based on the model, the mathematicians predicted the subsequent waves. The forecast was accurate in countries where mass vaccination was not introduced. The results are published in Mathematics.

The epidemy spreading rate within the country depends, among other things, on the climatic ...

In recent years, significant progress has been made towards the use of high-resolution peripheral computed tomography (HR-pQCT) imaging in research, and new potential for applications in the clinic have emerged, particularly with the advent of second generation devices.

A newly published state-of-the-art publication on the use and future directions of HR-PQCT provides a concise overview of current clinical applications as well as valuable guidance on the interpretation of results.

Specifically, it gives an overview of:

differences and reference data for HR-pQCT variables by age, sex, body composition and race/ethnicity;

fracture risk prediction using HR-pQCT, specifically in regard to bone microarchitecture in individuals ...

AURORA, COLORADO, June 16, 2021 -- Foresight Diagnostics, the emerging leader in blood-based lymphoma disease monitoring, announced today that clinical performance of its minimal residual disease (MRD) detection platform in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) will be presented at the 16th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma (ICML) on June 18-22, 2021. The oral presentation demonstrates the utility of Foresight Diagnostics' proprietary PhasED-Seq technology to improve MRD detection rates in DLBCL patients in low-disease burden settings.

"Foresight's MRD testing platform can detect relapsing disease 200 ...

Cancer cells can develop resistance to therapy through both genetic and non-genetic mechanisms. But it is unclear how and why one of these routes to resistance prevails. Understanding this 'choice' by the cancer cells may help us devise better therapeutic strategies. Now, the team of Prof. Jean-Christophe Marine (VIB-KU Leuven Center for Cancer Biology) shows that the presence of certain stem cells correlates with the development of nongenetic resistance mechanisms. Their study is published in the prestigious journal Cancer Cell.

Two routes to resistance

Even though cancer therapy has made great strides in the ...

African American mothers continue to have the lowest breastfeeding rates, even as the breastfeeding rates have risen in the U.S. over the past 25 years. Racism is an important barrier to breastfeeding, as examined in Part 2 of a special issue on "Breastfeeding and the Black/African American Experience: Cultural, Sociological, and Health Dimensions Through an Equity Lens," published in the peer-reviewed journal Breastfeeding Medicine. Click here to read the issue now.

The special issue is led by Guest Editor Sahira Long, MD, a pediatrician and lactation consultant.

Exploring how racism creates barriers to breastfeeding for Black mothers and how Black women resist racism during their quest to breastfeed are Catasha Davis, PhD and Aubrey Van Kirk Villalobos, DrPH, Milken Institute School ...

Since 2005, the guidelines for the care of unconscious cardiac arrest patients have been to cool the body temperature down to 33 degrees Celsius. A large, randomised clinical trial led by Lund University and Region Skåne in Sweden has shown that this treatment does not improve survival. The study is published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

"These results will affect the current guidelines", says Niklas Nielsen, researcher at Lund University and consultant in anaesthesiology and intensive care at Helsingborg Hospital, who led the study.

In the early 2000s, two studies in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that induced hypothermia in unconscious cardiac arrest patients ...

Conservationists have long warned of the dangers associated with bears becoming habituated to life in urban areas. Yet, it appears the message hasn't gotten through to everyone.

News reports continue to cover seemingly similar situations -- a foraging bear enters a neighbourhood, easily finds high-value food and refuses to leave. The story often ends with conservation officers being forced to euthanize the animal for public safety purposes.

Now, a new study by sustainability researchers in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science uses computer modelling to look at the best strategies to reduce human-bear conflict.

"It happens all the time, and unfortunately, humans are almost ...

Research shows that inhibiting necroptosis, a form of cell death, could be a novel therapeutic approach for treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an inflammatory lung condition, also known as emphysema, that makes it difficult to breathe.

Published in the prestigious American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, the study by a team of Australian and Belgian researchers, revealed elevated levels of necroptosis in patients with COPD.

By inhibiting necroptosis activity, both in the lung tissue of COPD patients as well as ...