(Press-News.org) A large, retrospective, multicenter study involving Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that convalescent plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients can dramatically improve likelihood of survival among blood cancer patients hospitalized with the virus.

The therapy involves transfusing plasma -- the pale yellow liquid in blood that is rich in antibodies -- from people who have recovered from COVID-19 into patients who have leukemia, lymphoma or other blood cancers and are hospitalized with the viral infection. The goal is to accelerate their disease-fighting response. Cancer patients may be at a higher risk of death related to COVID-19 because of their weakened immune systems.

The data, collected as part of a national registry, indicate that patients who received convalescent plasma from donors who had recovered from COVID-19 had a death rate of 13.3% compared with 24.8% for those who did not receive it.

The difference was especially striking among severely ill patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs). Such patients treated with convalescent plasma had a death rate of 15.8% compared with 46.9% for those who didn't receive the treatment.

"These results suggest that convalescent plasma may not only help COVID-19 patients with blood cancers whose immune systems are compromised, it may also help patients with other illnesses who have weakened antibody responses to this virus or to the vaccines," said Jeffrey P. Henderson, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine and of molecular microbiology at Washington University. "The data also emphasize the value of an antibody therapy such as convalescent plasma as a virus-directed treatment option for hospitalized COVID-19 patients."

The research is published June 17 in the journal JAMA Oncology.

Henderson collaborated with researchers from the international COVID-19 & Cancer Consortium (CCC19) formed over a year ago to collect and analyze data on the disease's unique interactions. More than 70 institutions in the consortium -- including Advocate Aurora Health in Wisconsin and Illinois, Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. -- participated in this study.

The scientists looked back at patient data to compare the 30-day mortality of 966 hospitalized adults with a blood cancer, such as leukemia, lymphoma or multiple myeloma, who also were diagnosed with COVID-19. The patients, whose average age was 67, were hospitalized at some point from March 17, 2020, through Jan. 21, 2021, due to complications from COVID-19.

Of the patients studied, 143 received convalescent plasma, and 823 did not. Of the 338 patients admitted to ICUs because of severe COVID-19 symptoms, such as difficulty breathing or cardiac distress, those who received the treatment were more than twice as likely to survive.

"In March 2020, the Food and Drug Administration provided a pathway for hospitalized patients to receive COVID-19 convalescent plasma if requested by their physicians," Henderson explained. "After this, the decision to give convalescent plasma was made by physicians and patients on a case-by-case basis. There were no restrictions on when during the course of illness convalescent plasma could be given to patients."

Early in the pandemic, many scientists urged evaluation of convalescent plasma to treat the virus, based on the plasma's historical effectiveness in fighting other viruses. During the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, some newly infected patients were treated successfully with plasma from people who had recovered from the flu. Additionally, during the outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and 2003, health-care workers used plasma transfusion experimentally and, in many cases, successfully to treat small numbers of people. SARS is caused by a coronavirus closely related to the one that causes COVID-19.

However, limited data on the novel coronavirus also caused pause among physicians. Randomized controlled trials -- the gold standard in research -- proved elusive, in most cases, due to the time required to prepare and coordinate adequate trials, and the need for scientists to prioritize among multiple investigational treatment options. Some preliminary results also disappointed, showing convalescent plasma only worked as a treatment in the general patient population if infused within days after diagnosis in patients who hadn't yet progressed to having severe complications.

"As more COVID-19 patients began receiving convalescent plasma, we started hearing physicians around the country report remarkable clinical improvements following convalescent plasma infusions in COVID-19 patients with blood cancers and antibody deficiencies, some of whom were already very ill," said Henderson, one of several physicians who formed the COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Program Leadership Group to study the use of convalescent plasma for treating COVID-19. "I have seen one of my own patients with blood cancer quickly improve after receiving convalescent plasma. Similar stories that were often very detailed suggested that a formal study would help physicians with decisions they were already making on a daily basis."

During the past year, over phone calls, emails and Zoom chats, updates on convalescent plasma -- its historical success and its prospects for COVID-19 -- were a staple in conversations between Henderson and his longtime friend and co-author Michael Thompson, MD, PhD, who also was his roommate during undergraduate school at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Thompson is now an oncologist and hematologist at Advocate Aurora Health, and Advocate Aurora Research Institute, both in Wisconsin, as well as a member of the steering committee of the COVID-19 & Cancer Consortium.

"It became increasingly evident that patients with leukemia, lymphoma and other blood cancers were particularly susceptible to severe COVID-19 and that COVID-19 may develop in a unique way in these patients," said Henderson. "We discussed that we might learn something from patients in the COVID-19 & Cancer Consortium, and things started to snowball from there."

Henderson contacted fellow researchers in the COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Program, including Michael J. Joyner, MD, who is a professor of anesthesiology at the Mayo Clinic and works closely with the FDA. Thompson reached out to Jeremy Warner, MD -- a professor of medicine at Vanderbilt, a steering committee member of the COVID-19 consortium and who operates the CCC19 registry. Together, the researchers plumbed the group's registry of de-identified data abstracted from medical records.

"The data started coming fast and furious," Henderson recalled.

"Given that patients with blood cancers have higher mortality rates from COVID-19, we suspect our findings, along with other similar cases not in this database, support using convalescent plasma to improve survival in these patients," Thompson said.

Henderson and Thompson contributed equally as the study's first authors. Joyner is a co-author, and Warner is the senior author. "Despite the inevitable limitations of retrospective data, we find these results compelling and certainly hope that they will be quickly investigated in a prospective clinical trial," Warner added. "We are exploring future research, including whether there is an interplay between patient factors and treatments received prior to the development of COVID-19, such as B-cell depleting monoclonal antibodies."

INFORMATION:

A new article, published as a Perspective in the journal Conservation Science and Practice, introduces a rapid assessment framework that can be used as a guide to make conservation and nature-based solutions more robust to future climate.

Climate change poses risks to conservation efforts, if practitioners assume a future climate similar to the past or present. For example, more frequent and intense disturbances, such as wildfire or drought-induced tree mortality, can threaten projects that are designed to enhance habitat for forest-dependent species and sequester carbon. Overlooking such climate-related risks can result in failed conservation investments and negative outcomes for people, biodiversity, and ecosystem integrity as well as lead to carbon-sink reversal. Drawing ...

The Black Sea is an unusual body of water: below a depth of 150 metres the dissolved oxygen concentration sinks to around zero, meaning that higher life forms such as plants and animals cannot exist in these areas. At the same time, this semi-enclosed sea stores comparatively large amounts of organic carbon. A team of researchers led by Dr Gonzalo V. Gomez-Saez and Dr Jutta Niggemann from the University of Oldenburg's Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment (ICBM) has now presented a new hypothesis as to why organic compounds accumulate in the depths of the Black Sea - and other oxygen-depleted waters in the scientific journal Science Advances.

The researchers posit that reactions with hydrogen sulfide play an important role in stabilizing ...

New Brunswick, N.J. (June 17, 2021) - Babies born by cesarean section don't have the same healthy bacteria as those born vaginally, but a Rutgers-led study for the first time finds that these natural bacteria can be restored.

The study appears in the journal Med.

The human microbiota consists of trillions of bacteria, viruses, fungi and other microorganisms - some beneficial, some harmful -- that live in and on our bodies. Women naturally provide these pioneer colonizers to their babies' sterile bodies during labor and birth, helping their immune system to develop. But antibiotics and C-sections disturb this passing of microbes and are related to increased risks of obesity, asthma and metabolic ...

Woodlands along streams and rivers are an important part of California's diverse ecology. They are biodiversity hotspots, providing various ecosystem services including carbon sequestration and critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. But our land and water use have significantly impacted these ecosystems, sometimes in unexpected ways.

A team of researchers, including two at UC Santa Barbara, discovered that some riparian woodlands are benefitting from water that humans divert for our own needs. Although it seems like a boon to these ecosystems, the artificial ...

SAN ANTONIO (June 17, 2021) -- Middle-aged people with depressive symptoms who carry a genetic variation called apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 may be more at risk to develop tau protein accumulations in the brain's emotion- and memory-controlling regions, a new study by researchers from The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio) and collaborating institutions suggests.

The Journal of Alzheimer's Disease published the findings in its June 2021 print issue. The research is based on depression assessments and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging conducted among 201 participants in the multigenerational Framingham Heart Study. The mean age of these participants was 53.

Decades before diagnosis

PET scans typically are conducted ...

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., June 17, 2021 -- A research team from Los Alamos National Laboratory and Purdue University have developed bio-inks for biosensors that could help localize critical regions in tissues and organs during surgical operations.

"The ink used in the biosensors is biocompatible and provides a user-friendly design with excellent workable time frames of more than one day," said Kwan-Soo Lee, of Los Alamos' Chemical Diagnostics and Engineering group.

The new biosensors allow for simultaneous recording and imaging of tissues and organs during surgical procedures.

"Simultaneous recording and imaging could be useful during heart surgery in localizing critical regions and guiding surgical interventions such as a procedure for restoring normal ...

Nanodecoys made from human lung spheroid cells (LSCs) can bind to and neutralize SARS-CoV-2, promoting viral clearance and reducing lung injury in a macaque model of COVID-19. By mimicking the receptor that the virus binds to rather than targeting the virus itself, nanodecoy therapy could remain effective against emerging variants of the virus.

SARS-CoV-2 enters a cell when its spike protein binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor on the cell's surface. LSCs - a natural mixture of lung epithelial stem cells and mesenchymal cells - also express ACE2, making them a perfect vehicle ...

Current approaches for planning relocation for potentially millions of people affected by climate change and related risks are "woefully inadequate" and risk worsening societal inequities, experts wrote in a policy perspective on June 17 in Science. Policymakers and scientists need to rethink how they work together to develop, communicate and carry out relocation plans.

"Relocation involves moving people away from risk and into totally new settings," said the team of experts led by Richard Moss. Moss is a Gerhard R. Andlinger Visiting Fellow at Princeton's Andlinger Center ...

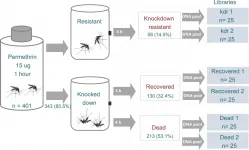

The Yellow fever mosquito (scientific name, Aedes aegypti) spreads multiple untreatable viruses in humans and is primarily controlled using a pesticide called permethrin. However, many mosquitoes are evolving resistance to the pesticide. A new study by Karla Saavedra-Rodriguez of Colorado State University and colleagues, published in the journal PLOS Genetics, identifies mutations linked to different permethrin resistance strategies, which threaten our ability to control disease outbreaks.

When treated mosquitoes encounter permethrin in the wild, they will do one of the following: immediately die, be knocked out but recover, or be unaffected. Saavedra-Rodriguez and her colleagues decided to investigate the genetic variations that lead to these ...

A new treatment approach focused on fixing cell damage, rather than fighting the virus directly, is effective against SARS-CoV-2 in lab models.

Combination of two drugs reduces spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection in cells by up to 99.5%.

If found safe for human use, this anti-viral treatment would make

COVID-19 symptoms milder and speed up recovery times.

When a person is infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, it invades their cells and uses them to replicate - which puts the cells under stress. Current approaches to dealing with infection target the virus itself with antiviral drugs. But ...