(Press-News.org) University of Delaware disaster researcher A.R. Siders said it's time to put all the options on the table when it comes to discussing climate change adaptation.

Managed retreat -- the purposeful movement of people, buildings and other assets from areas vulnerable to hazards -- has often been considered a last resort. But Siders said it can be a powerful tool for expanding the range of possible solutions to cope with rising sea levels, flooding and other climate change effects when used proactively or in combination with other measures.

Siders, a core faculty member in UD's Disaster Research Center, and Katharine J. Mach, associate professor at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, provide a prospective roadmap for reconceptualizing the future using managed retreat in a new paper published online in Science on June 17, 2021.

"Climate change is affecting people all over the world, and everyone is trying to figure out what to do about it. One potential strategy, moving away from hazards, could be very effective, but it often gets overlooked," said Siders, assistant professor in the Joseph R. Biden, Jr. School of Public Policy and Administration and the Department of Geography and Spatial Sciences. "We are looking at the different ways society can dream bigger when planning for climate change and how community values and priorities play a role in that."

Retreat does not mean defeat

Managed retreat has been happening for decades all over the United States at a very small scale with state and/or federal support. Siders pointed to Hurricanes Harvey and Florence as weather events that caused homeowners near the Gulf of Mexico to seek government support for relocation. Locally, towns such as Bowers Beach, near the Delaware coast, have used buyouts to remove homes and families from flood-prone areas, an idea that Southbridge in Wilmington is also exploring.

People often oppose the idea of leaving their homes, but Siders said thinking seriously about managed retreat sooner and in context with other available tools can reinforce decisions by prompting difficult conversations. Even if communities decide to stay in place, identifying the things community members value can help them decide what they want to maintain and what they purposely want to change.

"If the only tools you think about are beach nourishment and building walls, you're limiting what you can do, but if you start adding in the whole toolkit and combining the options in different ways, you can create a much wider range of futures," she said.

In the paper, Siders and Mach argue that long-term adaptation will involve retreat. Even traditionally accepted visions of the future, like building flood walls and elevating threatened structures, will involve small-scale retreat to make space for levees and drainage. Larger-scale retreat may be needed for more ambitious transformations, such as building floating neighborhoods or cities, turning roads into canals in an effort to live with the water, or building more dense, more compact cities on higher ground.

Some, but not all these futures currently exist.

In the Netherlands, the municipality of Rotterdam has installed floating homes in Nassau harbor that move with the tides, providing a sustainable waterfront view for homeowners while making room for public-friendly green space along the water. In New York City, one idea under consideration is building into the East River to accommodate a floodwall. Both cities are using combination strategies that leverage more than one adaptation tool.

Adaptation decisions don't have to be either/or decisions. However, it is important to remember that these efforts take time, so planning should begin now.

"Communities, towns, and cities are making decisions now that affect the future," said Siders. "Locally, Delaware is building faster inside the floodplain than outside of it. We are making plans for beach nourishment and where to build seawalls. We're making these decisions now, so we should be considering all the options on the table now, not just the ones that keep people in place."

According to Siders, the paper is a conversation starter for researchers, policymakers, communities and residents that are invested in helping communities thrive amid changing climate. These discussions, she said, shouldn't focus solely on where we need to move from, but also where we should avoid building, where new building should be encouraged, and how we should build differently.

"Managed retreat can be more effective in reducing risk, in ways that are socially equitable and economically efficient, if it is a proactive component of climate-driven transformations," said Mach. "It can be used to address climate risks, along with other types of responses like building seawalls or limiting new development in hazard-prone regions."

Globally, Siders said the U.S. is in a privileged position, in terms of the available space, money and resources, relative to other countries facing more complicated futures. The Republic of Kiribati, a chain of islands in the central Pacific Ocean, for example, is expected to be under water in the future. Some of its islands already are uninhabitable.

The Kiribati government has bought land in Fiji for relocation and is developing programs with Australia and New Zealand to provide skilled workforce training so the Kiribati people can migrate with dignity when the time comes. Challenges remain, though, since not everyone is on board with moving.

In a recent special issue of the Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, edited and introduced by Siders and Idowu (Jola) Ajibade at Portland State University, researchers examined the social justice implications of managed retreat in examples from several countries, including the U.S., Marshall Islands, New Zealand, Peru, Sweden, Taiwan, Austria and England. The scientists explored how retreat affects groups of people and, in the U.S., specifically considered how retreat affects marginalized populations.

So, how can society do better? According to Siders, it starts with longer-term thinking.

"It's hard to make good decisions about climate change if we are thinking 5-10 years out," said Siders. "We are building infrastructure that lasts 50-100 years; our planning scale should be equally long."

Siders will give a keynote address and research presentation on the topic at a virtual managed retreat conference at Columbia University, June 22-25, 2021.

INFORMATION:

KIYATEC, Inc. announced today the publication of new peer-reviewed data that establishes clinically meaningful prediction of patient-specific responses to standard of care therapy, prior to treatment, in newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM) and other high-grade glioma (HGG) patients. The results, the interim data analysis of the company's 3D-PREDICT clinical study, were published June 16, 2021 in Neuro-Oncology Advances, an open access clinical journal.

A goal of the study, which continues to enroll, was for the test's prospective, patient-specific response prediction to achieve statistical significance for ...

Researchers from Bentley University, in partnership with Waltham Council on Aging in Massachusetts, and as part of a study funded by the National Science Foundation, have been exploring how the elderly use smart speakers at home. Waltham, a satellite city about eight miles west of Cambridge has a population of about 60,000, with about one in six being an elderly citizen. The purpose of the study was to understand how the elderly use the smart speaker technology at home. A smart speaker is a hardware device that is always-on. When a wake-word triggers the software contained in the device, the smart speaker listens to the command to provide a response or carry out the command (accessing resources ...

When Ana K. Spalding, a Research Associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and Assistant Professor of Marine and Coastal Policy at Oregon State University (OSU) talks about mentorship in academia, she describes it as meaningful relationship. It goes beyond conversations about research and publications, and into shared experiences. This is just one approach--proposed by Spalding and 23 other women scientists from around the world, in a new article published in PLOS Biology--that calls for a shift in the value system of science to emphasize a more equal, diverse and inclusive academic culture.

The authors came together after reading a ...

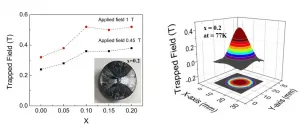

Superconductors are something like a miracle in the modern world. Their unique property of zero resistance can revolutionize power transmission and transport (e.g., Maglev train). However, most of the conventional superconductors require cooling down to extremely low temperatures that can only be achieved with liquid helium, a rather expensive coolant. Material scientists are now investigating "high-temperature superconductors" (HTSs) that can be cooled to a superconducting state by using the significantly cheaper liquid nitrogen (which has a remarkably higher temperature than liquid helium). ...

TROY, N.Y. -- Optoelectronic materials that are capable of converting the energy of light into electricity, and electricity into light, have promising applications as light-emitting, energy-harvesting, and sensing technologies. However, devices made of these materials are often plagued by inefficiency, losing significant useful energy as heat. To break the current limits of efficiency, new principles of light-electricity conversion are needed.

For instance, many materials that exhibit efficient optoelectronic properties are constrained by inversion symmetry, a physical property that limits engineers' control of electrons in the material and their options for designing novel or efficient devices. In research published today in Nature ...

With sorghum poised to become an important crop grown by Pennsylvania farmers, Penn State researchers, in a new study, tested more than 150 germplasm lines of the plant for resistance to a fungus likely to hamper its production.

Sorghum, a close relative to corn, is valuable for yielding human food, animal feed and biofuels. Perhaps its most notable attribute is that the grain it produces is gluten free. Drought resistant and needing a smaller amount of nutrients than corn to thrive, sorghum seems to be a crop that would do well in the Keystone State's ...

The article 'The RNA Atlas expands the catalog of human non-coding RNAs', published today in Nature Biotechnology, is the result of more than five years of hard work to further unravel the complexity of the human transcriptome. Never before such a comprehensive effort was undertaken to characterize all RNA-molecules in human cells and tissues.

RNAs in all shapes and sizes

Our transcriptome is - analogous to our genome - the sum of all RNA molecules that are transcribed from the DNA strands that make up our genome. However, there's no 1-on-1 relationship with the latter. Firstly, each cell and tissue hasve a unique transcriptomes, with varying RNA production and compositions, including tissue-specific RNAs. Secondly, ...

Additive manufacturing offers an unprecedented level of design flexibility and expanded functionality, but the quality and process can drastically differ across production machines, according to Hui Yang, a professor of industrial engineering at Penn State. With applications in aerospace, health care and automotive industries with potential for mass customization, additive manufacturing needs quality management.

To address this concern, Yang and a team of researchers from Penn State, University of Nebraska--Lincoln and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) proposed the design, development and implementation of a new data-driven methodology for quality control in additive manufacturing. They published their work in the Proceedings ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA--Geothermal energy systems have the potential to power the world and become the leading technology for reducing greenhouse gas emissions if we can drill down far enough into the Earth to access the conditions necessary for economic viability and release the heat beneath our feet. END ...

SAN ANTONIO (June 17, 2021) -- Convalescent plasma therapy was associated with better survival in blood cancer patients hospitalized with COVID-19, especially in sicker patients. The findings by the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) are newly published in the peer-reviewed journal JAMA Oncology.

The Mays Cancer Center, home to UT Health San Antonio MD Anderson, is part of the CCC19. The international consortium is composed of 124 medical centers and institutions in North and South America that conduct research to learn how COVID-19 affects cancer patients.

Dimpy Shah, MD, PhD, is an epidemiologist and assistant professor of population health sciences at The University of Texas Health ...