(Press-News.org) Rainfall associated with the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), the belt of converging trade winds and rising air that encircles the Earth near the Equator, affects the food and water security of approximately 1 billion people worldwide. They include about 11% of the Brazilian population, concentrated in four states of the Northeast region - Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará, Piauí, and Maranhão. Large swathes of these states have a semi-arid climate, and about half of all their annual rainfall occurs in only two months (March and April), when the tropical rain belt reaches its southernmost position, over the north of the Northeast region. During the rest of the year, the tropical rain belt shifts further north. For example, it is responsible for peak rainfall in the coastal region of Venezuela in July and August.

Projecting the future behavior of precipitation in semi-arid areas like these is fundamental for society to be able to anticipate possible shifts in rainfall patterns due to ongoing climate change. A study by Cristiano Chiessi, a professor at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil, and collaborators shows that precipitation in the north of Brazil's Northeast region has systematically decreased in the last 5,000 years, contrary to an important paradigm in paleoclimatology. This revised view of what happened in the past helps produce a more realistic scenario for what may happen in the future.

An article on the study is published in Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. The study was supported by FAPESP.

"According to the prevailing paradigm, the tropical rain belt has migrated southward in the last 5,000 years. Our research suggests instead that its latitudinal oscillation range contracted, so that it now oscillates within a narrower band," Chiessi told Agência FAPESP.

Valuable information regarding the responses of the climate system to different conditions is recorded in geological sediments deposited on the seabed. The study involves three independent indicators of precipitation deriving from sediments collected along the mouth of the Parnaíba on the Piauí-Maranhão border.

"We analyzed the ratio between levels of the chemical elements titanium and calcium. The titanium comes from continental rock erosion, while the calcium comes from the shells of marine organisms," Chiessi said. "We also estimated the rate at which continental sediments accumulated on the seabed, and the composition of hydrogen isotopes in continental plant wax found in marine sediment. These three datasets, together with our analysis of numerical climate model outputs, pointed to contraction of the tropical rain belt in the last 5,000 years, rather than the suggested southward migration."

The study also shows that surface temperature distribution in the two hemispheres is a key factor in the tropical rain belt's position, also in contrast with the prevailing paradigm.

"According to the paradigm, southward migration of the tropical rain belt was due to a gradual increase in radiation received from the Sun by the southern hemisphere during the summer. The opposite occurred in the northern hemisphere, increasingly hindering northward migration of the tropical rain belt. However, our attention was drawn to two weaknesses in this model," Chiessi said. "The first was the assumption that the rain belt's position was determined by surface temperature distribution in both hemispheres, which don't necessarily respond in a linear manner to the distribution of solar radiation. Secondly, the evidence supporting the paradigm was located almost solely in the northern hemisphere. There was no proof of the migration in the southern hemisphere."

Although solar radiation did undergo the changes described, he went on, responses in the hemispheres were different owing to the difference in the area of the continents and oceans in each one (continents respond faster than oceans to changes in solar radiation). "It's therefore necessary to revise the paradigm that has influenced paleoclimatology for two decades," he said.

Numerical climate models suggest that by the end of this century the tropical rain belt's latitudinal oscillation range will contract, further reducing rainfall in the northern portion of Brazil's Northeast region, with potentially severe social and environmental consequences. However, if the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) becomes significantly weaker, reaching the tipping point predicted in another study by Chiessi, the warming of the South Atlantic will exceed that of the North Atlantic, forcing the rain belt southward. "This would have negative consequences in various parts of the world. In Brazil, however, it would prevent an even greater decrease in precipitation in the northern portion of the Northeast," he said (more at: agencia.fapesp.br/23134/).

INFORMATION:

About São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) is a public institution with the mission of supporting scientific research in all fields of knowledge by awarding scholarships, fellowships and grants to investigators linked with higher education and research institutions in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. FAPESP is aware that the very best research can only be done by working with the best researchers internationally. Therefore, it has established partnerships with funding agencies, higher education, private companies, and research organizations in other countries known for the quality of their research and has been encouraging scientists funded by its grants to further develop their international collaboration. You can learn more about FAPESP at http://www.fapesp.br/en and visit FAPESP news agency at http://www.agencia.fapesp.br/en to keep updated with the latest scientific breakthroughs FAPESP helps achieve through its many programs, awards and research centers. You may also subscribe to FAPESP news agency at http://agencia.fapesp.br/subscribe.

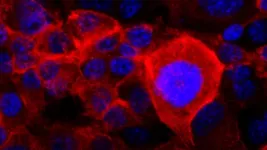

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) -- The secret to healthier skin and joints may reside in gut microorganisms. A study led by UC Davis Health researchers has found that a diet rich in sugar and fat leads to an imbalance in the gut's microbial culture and may contribute to inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis. ...

New research published in the Journal of Medicinal Food suggests eating prunes each day can improve risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) including raising antioxidant capacity and reducing inflammation among healthy, postmenopausal women.

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death worldwide posing a significant public health challenge.

The research led by San Diego State University reveals that prunes can positively affect heart disease risk.

"When you look at our prior research and the research of others combined with this new data, you'll see consistent ...

"Workforce issues are the most significant challenges facing the long-term care industry," states the opening editorial of a new special issue of The Gerontologist titled " END ...

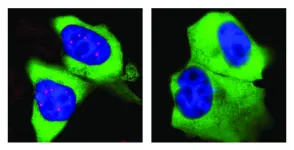

Almost all cells in our body contain a nucleus: a somewhat spherical structure that is separated from the rest of the cell by a membrane. Each nucleus contains all the genetic information of the human being. So it serves as a kind of library - but one with strict requirements: If the cell needs the building instructions for a protein, it won't simply borrow the original information. Instead, a transcript of it is made in the nucleus.

The machinery required for this is very complex, not least because the transcripts are not simple copies. In addition to essential information, genes also contain numerous passages of meaningless "garbage". They are removed when the transcript is made. Biologists call this editorial revision ...

Persons suffering from the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis can develop various neurological symptoms caused by damage to the nervous system. Especially in early stages, these may include sensory dysfunction such as numbness or visual disturbances. In most patients, MS starts with recurring episodes of neurological disability, called relapses or demyelinating events. These clinical events are followed by a partial or complete remission. Especially in the beginning, the symptoms vary widely, so that it is often difficult even for experienced doctors to interpret them correctly to arrive at a diagnosis of MS.

Above-average numbers of medical appointments

It has been evident for some ...

The most comprehensive molecular study to date of the brains of people who died of COVID-19 turned up unmistakable signs of inflammation and impaired brain circuits.

Investigators at the Stanford School of Medicine and Saarland University in Germany report that what they saw looks a lot like what's observed in the brains of people who died of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

The findings may help explain why many COVID-19 patients report neurological problems. These complaints increase with the severity of infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. And they can persist as an aspect of "long COVID," a long-lasting disorder that sometimes ...

If only it were as simple as finding more grassland for an antelope.

The story of efforts to conserve the endangered oribi in South Africa represent a diaspora of issues as varied as the people who live there. On its surface, like many threatened species, you have conflict between a need for habitat and private landownership.

But dig a little deeper and you'll uncover a seedy underbelly of political corruption, gambling, struggles over land, and racial tensions. No matter how much success is made through more traditional conservation efforts, says a new study by a University of Georgia researcher, the species ...

Rutgers scientists have used a diagnostic technique for the first time in the opioid addiction field that they believe has the potential to determine which opioid-addicted patients are more likely to relapse.

Using an algorithm that looks for patterns in brain structure and functional connectivity, researchers were able to distinguish prescription opioid users from healthy participants. If treatment is successful, their brains will resemble the brain of someone not addicted to opioids.

"People can say one thing, but brain patterns do not lie," said Suchismita Ray, lead researcher and an associate professor in the Department of Health Informatics at Rutgers School of Health Professions. "The brain patterns that ...

Cancer cells can become resistant to treatments through adaptation, making them notoriously tricky to defeat and highly lethal. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Cancer Center Director David Tuveson and his team investigated the basis of "adaptive resistance" common to pancreatic cancer. They discovered one of the backups to which these cells switch when confronted with cancer-killing drugs.

KRAS is a gene that drives cell division. Most pancreatic cancers have a mutation in the KRAS protein, causing uncontrolled growth. But, drugs that shut off mutant KRAS do not stop the proliferation. ...

Lifestyle changes for demand-side climate change mitigation is gaining more and more importance and attention. A new IIASA-led study set out to understand the full potential of behavior change and what drives such changes in people's choices across the world using data from almost two billion Facebook profiles.

Modern consumption patterns, and especially livestock production in the agricultural sector to sustain the world's growing appetite for animal products, are contributing to and speeding the advance of interconnected issues like climate change, air pollution, and biodiversity ...