(Press-News.org) University of Maryland researchers created the first high-resolution image of an expanding bubble of hot plasma and ionized gas where stars are born. Previous low-resolution images did not clearly show the bubble or reveal how it expanded into the surrounding gas.

The researchers used data collected by the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) telescope to analyze one of the brightest, most massive star-forming regions in the Milky Way galaxy. Their analysis showed that a single, expanding bubble of warm gas surrounds the Westerlund 2 star cluster and disproved earlier studies suggesting there may be two bubbles surrounding Westerlund 2. The researchers also identified the source of the bubble and the energy driving its expansion. Their results were published in The Astrophysical Journal on June 23, 2021.

"When massive stars form, they blow off much stronger ejections of protons, electrons and atoms of heavy metal, compared to our sun," said Maitraiyee Tiwari, a postdoctoral associate in the UMD Department of Astronomy and lead author of the study. "These ejections are called stellar winds, and extreme stellar winds are capable of blowing and shaping bubbles in the surrounding clouds of cold, dense gas. We observed just such a bubble centered around the brightest cluster of stars in this region of the galaxy, and we were able to measure its radius, mass and the speed at which it is expanding."

The surfaces of these expanding bubbles are made of a dense gas of ionized carbon, and they form a kind of outer shell around the bubbles. New stars are believed to form within these shells. But like soup in a boiling cauldron, the bubbles enclosing these star clusters overlap and intermingle with clouds of surrounding gas, making it hard to distinguish the surfaces of individual bubbles.

Tiwari and her colleagues created a clearer picture of the bubble surrounding Westerlund 2 by measuring the radiation emitted from the cluster across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from high-energy X-rays to low-energy radio waves. Previous studies, which only radio and submillimeter wavelength data, had produced low-resolution images and did not show the bubble. Among the most important measurements was a far-infrared wavelength emitted by a specific ion of carbon in the shell.

"We can use spectroscopy to actually tell how fast this carbon is moving either towards or away from us," said Ramsey Karim (M.S. '19, astronomy), a Ph.D. student in astronomy at UMD and a co-author of the study. "This technique uses the Doppler effect, the same effect that causes a train's horn to change pitch as it passes you. In our case, the color changes slightly depending on the velocity of the carbon ions."

By determining whether the carbon ions were moving toward or away from Earth and combining that information with measurements from the rest of the electromagnetic spectrum, Tiwari and Karim were able to create a 3D view of the expanding stellar-wind bubble surrounding Westerlund 2.

In addition to finding a single, stellar wind-driven bubble around Westerlund 2, they found evidence of new stars forming in the shell region of this bubble. Their analysis also suggests that as the bubble expanded, it broke open on one side, releasing hot plasma and slowing expansion of the shell roughly a million years ago. But then, about 200,000 or 300,000 years ago, another bright star in Westerlund 2 evolved, and its energy re-invigorated the expansion of the Westerlund 2 shell.

"We saw that the expansion of the bubble surrounding Westerlund 2 was reaccelerated by winds from another very massive star, and that started the process of expansion and star formation all over again," Tiwari said. "This suggests stars will continue to be born in this shell for a long time, but as this process goes on, the new stars will become less and less massive."

Tiwari and her colleagues will now apply their method to other bright star clusters and warm gas bubbles to better understand these star-forming regions of the galaxy. The work is part of a multi-year NASA-supported program called FEEDBACK.

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors of the research paper from UMD's Department of Astronomy include Research Scientists Marc Pound and Mark Wolfire and Adjunct Professor Alexander Tielens.

This work was supported by the NASA-funded FEEDBACK project (Award No. SOF070077). The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the views of this organization.

The research paper, "SOFIA FEEDBACK Survey: Exploring the Dynamics of the Stellar-wind-driven Shell of RCW 49" and the author list is: Tiwari, M., Karim, R., Pound, M. W., Wolfire, M., Jacob, A., Buchbender, C., Güsten, R., Guevara, C., Higgins, R. D., Kabanovic, S., Pabst, C., Ricken, O., Schneider, N., Simon, R., Stutzki, J., Tielens, A. G. G. M., was published on June 23, 2021, in The Astrophysical Journal.

Media Relations Contact: Kimbra Cutlip, 301-405-9463, kcutlip@umd.edu

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, Md. 20742

http://www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 9,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $200 million.

In the United States, more than 12 million children hear a minority language at home from birth. More than two-thirds hear English as well, and they reach school age with varying levels of proficiency in two languages. Parents and teachers often worry that acquiring Spanish will interfere with children's acquisition of English.

A first-of-its kind study in U.S.-born children from Spanish-speaking families led by researchers at Florida Atlantic University finds that minority language exposure does not threaten the acquisition of English by children in the U.S. and that there is no trade-off ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Nineteenth- and 20th-century archaeologists often made sweeping claims about Native cultures, suggesting that everyone who lived in a particular region at a given time shared the same attitudes and practices. A new study of pipes recovered from Hopewell sites in Illinois and Ohio challenges this assumption, revealing that the manufacture, import, export and use of pipestone pipes for smoking varied significantly between the groups, even though they engaged in trade with one another.

The Hopewell era ran from about 50 B.C. to A.D. 250. The new findings are reported in the journal American Antiquity.

The Havana and Scioto Hopewell people, who lived in what is now Illinois ...

A Canadian research team has uncovered a new mechanism involved in Bourneville tuberous sclerosis (BTS), a genetic disease of childhood. The team hypothesizes that a mutation in the TSC1 gene causes neurodevelopmental disorders that develop in conjunction with the disease.

Seen in one in 6,000 children, tuberous sclerosis causes benign tumours or lesions that can affect various organs such as the brain, kidneys, eyes, heart and skin. While some patients lead healthy lives, others have significant comorbidities, such as epilepsy, autism and learning disabilities.

Although the role that the TSC1 gene plays in the disease is already known, Montreal scientists have only now identified a critical period in the postnatal development ...

When a pregnant person declines a recommended treatment such as prenatal testing or an epidural, tension and strife may ensue between the patient and provider, according to a new analysis by researchers at NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing and the University of British Columbia.

"People should feel safe, respected, and engaged in their maternity care, but our findings suggest that when providers do not listen to patients, it can foster mistrust and avoidance," said P. Mimi Niles, PhD, MPH, CNM, assistant professor at NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing and the lead author of the study, which is published in the journal PLOS ONE. ...

Middle school, a time when children's brains are undergoing significant development, is often also a time of new challenges in navigating the social world. Recent research from the Center for BrainHealth at UT Dallas demonstrates the power of combining a virtual platform with live coaching to help students enhance their social skills and confidence in a low-risk environment.

In this study, BrainHealth researchers partnered with low-income public middle schools in Dallas. Teachers recommended 90 students to participate in virtual training sessions via ...

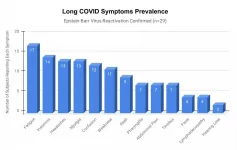

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation resulting from the inflammatory response to coronavirus infection may be the cause of previously unexplained long COVID symptoms -- such as fatigue, brain fog, and rashes -- that occur in approximately 30% of patients after recovery from initial COVID-19 infection. The first evidence linking EBV reactivation to long COVID, as well as an analysis of long COVID prevalence, is outlined in a new long COVID study published in the journal Pathogens.

"We ran EBV antibody tests on recovered COVID-19 patients, comparing EBV reactivation rates of those with long COVID symptoms to those without ...

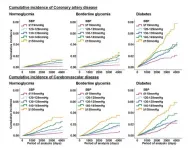

Niigata, Japan - An estimated 1.13 billion people worldwide have hypertension or high blood pressure, and two-thirds of these individuals are living in low- and middle-income countries. Blood pressure is the force manifested by circulating blood against the walls of the body's arteries, the major blood vessels in the body. Hypertension is when blood pressure is too high.

Blood pressure is written as two numbers. The first (systolic) number represents the pressure in blood vessels when the heart contracts or beats. The second (diastolic) number represents the pressure in the vessels when the heart rests between beats. Hypertension is diagnosed if, when it is measured on two different days, the systolic blood pressure (SBP) readings on both days is ≥140 mmHg and/or the diastolic ...

Supercomputers could find themselves out of a job thanks to a suite of new machine learning models that produce rapid, accurate results using a normal laptop.

Researchers at the ARC Centre of Excellence in Exciton Science, based at RMIT University, have written a program that predicts the band gap of materials, including for solar energy applications, via freely available and easy-to-use software. Band gap is a crucial indication of how efficient a material will be when designing new solar cells.

Band gap predictions involve quantum and atomic-scale chemical calculations ...

It's one of the iconic images of early Antarctic exploration: the heroic explorer sledging across the icy wastes towed by his trusty team of canine companions.

But new research analysing a century-old dog biscuit suggests the animals in this picture were probably marching on half-empty stomachs: early British Antarctic expeditions underfed their dogs.

In a paper just published in Polar Record, researchers from Canterbury Museum, Lincoln University and University of Otago in New Zealand analysed the history and contents of Spratt's dog cakes, the chow of choice for the canine members of early Antarctic expeditions.

Lead author, ...

Two mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 have proven safe and effective in clinical trials, as well as in the millions of people who have been vaccinated so far. But how prior SARS-CoV-2 infection affects vaccine response, and how long that response lasts, are still uncertain. Now, a new study in ACS Nano supports increasing evidence that people who had COVID-19 need only one vaccine dose, and that boosters could be necessary for everyone in the future.

In clinical trials, the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines were about 95% effective in protecting against symptomatic infections. Both mRNA vaccines trigger the immune system to produce antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD), and two doses are necessary to provide immunity in people ...