(Press-News.org) AMES, Iowa -- A new study of small Iowa towns found that vulnerable populations within those communities face significantly more public health risks than statewide averages.

The study, published this week in PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed open access journal, was led by Benjamin Shirtcliff, associate professor of landscape architecture at Iowa State University.

He focused on three Iowa towns - Marshalltown, Ottumwa and Perry - as a proxy for studying shifting populations in rural small towns, in particular how vulnerable populations in these towns are affected by their built environment (where people live and work) and environmental risks. Shirtcliff wants to understand how small towns can prioritize investment into their built environment for vulnerable populations on the heels of declining economic resources due to population change.

The study found the three towns have significantly higher environmental exposures than state averages, including more exposure to diesel, air toxins, lead paint in older homes and proximity to potential chemical accidents.

These risks are exacerbated for and increase physical and mental stress on populations with social vulnerability (minority status, low-income, linguistic isolation, below high school education, and populations under age 5 and over 64), which are also significantly higher in the three small towns than state averages.

With the growth of industrialized agriculture over the past few decades, small towns' populations have shifted: "...what environmental justice advocates describe as a 'double jeopardy' of injustice where people with the fewest resources reside in low-income communities with high level of environmental risk and unable defend against social threats like racism," according to the study.

Urban areas benefit from more green space, which would make it seem as if small towns surrounded by green landscapes would have greater benefits. That's not always the case, Shirtcliff says, due to the routine application of pesticides, fertilizers and other organic and inorganic toxins.

"There is a rural health paradox: These small towns may appear on the outside that they're healthier and safer, but the reality is that the metrics cities use are not really compatible," he said.

This exposes a knowledge gap in current research: Measures of environmental risk and design on vulnerable populations in urban areas are not comparable to those in small towns.

'Parallel communities'

Shirtcliff describes these small towns as having "parallel communities," or populations that rarely interact due to their opposing work and personal schedules, geography and language barriers.

This research began following one of Shirtcliff's design studios in Perry four years ago. During an interview with Jon Wolseth, assistant director of community and economic development with ISU Extension and Outreach, he and fellow researchers learned about the parallel communities in the town.

"When we think about public health these days, we think about viruses and epidemics," he said. "What's increasingly being supported through research is that the neighborhoods we live in have huge impacts on our mental and physical health."

As some Iowans move to more urban areas from small towns, the built environment they leave behind is sometimes neglected.

Now, there are new barriers that people in these towns face to report and seek care for poor health effects from their built environment. There is also sometimes an information barrier; for example, rural populations may not correlate higher rates of asthma with the landscape.

"Although the influx of foreign-born workers and their families to small towns has enabled economic growth in the hands of a local few, the stability of small towns is fragile," according to the study. "A decline in local investment coupled with aging infrastructure is likely to impact the built environments in small towns, potentially compounding deleterious effects as vulnerable populations bring families and become established."

Shirtcliff puts a call out to the landscape architecture profession, which can sometimes focus on broad-reaching issues such as major parks and environmental remediation, to also focus their efforts on "the banal, everyday 'human environment' where a sidewalk, street tree, and crosswalk make a fundamental difference." Low-cost interventions such as these can counteract "a mounting public health crisis in small towns," he says.

INFORMATION:

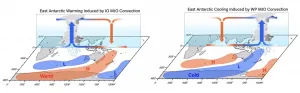

Our planet is warming due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions; but the warming differs from region to region, and it can also vary seasonally. Over the last four decades scientists have observed a persistent austral summer cooling on the eastern side of Antarctica. This puzzling feature has received world-wide attention, because it is not far away from one of the well-known global warming hotspots - the Antarctic Peninsula.

A new study published in the journal Science Advances by a team of scientists from the IBS Center for Climate Physics at Pusan National University in South Korea, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, Ewha Womans University, and National Taiwan ...

A new study from archaeologists at University of Sydney and Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, has provided important new evidence to answer the question "Who exactly were the Anglo-Saxons?"

New findings based on studying skeletal remains clearly indicates the Anglo-Saxons were a melting pot of people from both migrant and local cultural groups and not one homogenous group from Western Europe.

Professor Keith Dobney at the University of Sydney said the team's results indicate that "the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of early Medieval Britain were strikingly similar to contemporary Britain - full of people of different ancestries sharing a common language and culture".

The Anglo-Saxon (or early medieval) period in England runs from the 5th-11th centuries AD. Early Anglo-Saxon dates from ...

Newspapers regularly carry stories of terrifying shark attacks, but in a paper published today, Oxford-led researchers reveal their discovery of a 3,000-year-old victim - attacked by a shark in the Seto Inland Sea of the Japanese archipelago.

The research in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, shows that this body is the earliest direct evidence for a shark attack on a human and an international research team has carefully recreated what happened - using a combination of archaeological science and forensic techniques.

The grim discovery of the victim was made by Oxford researchers, J. Alyssa White and Professor Rick Schulting, while investigating evidence for violent trauma on the skeletal remains of prehistoric hunter-gatherers at ...

SAN ANTONIO, June 23, 2021 - A typical Western high-fat diet can increase the risk of painful disorders common in people with conditions such as diabetes or obesity, according to a groundbreaking paper authored by a team led by The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, also referred to as UT Health San Antonio.

Moreover, changes in diet may significantly reduce or even reverse pain from conditions causing either inflammatory pain - such as arthritis, trauma or surgery - or neuropathic pain, such as diabetes. The novel finding could help treat chronic-pain patients by simply altering diet or developing drugs that block ...

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – Mathematical models that describe the physical behavior of magnetic materials can also be used to describe the spread of the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

This is the conclusion of a study conducted in Brazil by researchers affiliated with São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Rio Claro and Ilha Solteira and reported in an article published in Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications.

The study was part of a project led by Mariano de Souza, a professor at UNESP’s Rio Claro Physics Department, and of the PhD research of Isys Mello, whose thesis advisor is Souza, last author of the article. Another co-author is Antonio Seridonio, a professor at UNESP’s Ilha Solteira Physics ...

Only 1 in 10 older adults in a large national survey who were found to have cognitive impairment consistent with dementia reported a formal medical diagnosis of the condition.

Using data from the Health and Retirement Study to develop a nationally representative sample of roughly 6 million Americans age 65 or older, researchers at the University of Michigan, North Dakota State University and Ohio University found that 91% of people with cognitive impairment consistent with dementia told questioners they had a formal medical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or dementia.

"(The discrepancy) was higher than I was expecting," ...

Flavoring can change how the brain responds to e-cigarette aerosols that contain nicotine, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers. Andrea Hobkirk and her team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to understand how the brain's reward areas react to e-cigarette aerosol with and without flavor.

"There are nearly 12 million e-cigarette users in the United States," Hobkirk, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State College of Medicine, said. "The vast majority use e-cigarettes with menthol, mint, fruity and dessert-type flavors. Although regulations that limit the sale of flavored e-cigarettes may help curb use among youth, they might also stop adults from using e-cigarettes as a smoking ...

Researchers from Bentley University have been exploring how readers at partisan news sites respond to news events that challenge their worldview.

In a forthcoming paper in the journal ACM Transactions on Social Computing, they report results of a study that examines reader comments on stories surrounding the 2017 Roy Moore Alabama senate race at two partisan news sites: a left-leaning news site (Daily Kos) and a right-leaning news site (Breitbart). They consider the alleged sexual misconduct of Mr. Moore as a challenging news event for the right-leaning readers; and the subsequent nomination of Mr. Moore as the Republican candidate as a challenging news event for the left-leaning readers.

Their analysis identifies the obstacles that readers face as they try to make sense ...

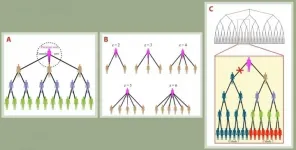

NEW YORK CITY, June 23, 2021 -- From amoebas to zebras, all living things evolve. They change over time as pressures from the environment cause individuals with certain traits to become more common in a population while those with other traits become less common.

Cancer is no different. Within a growing tumor, cancer cells with the best ability to compete for resources and withstand environmental stressors will come to dominate in frequency. It's "survival of the fittest" on a microscopic scale.

But fitness -- how well suited any particular individual is to its environment -- isn't set in stone; it can change when the environment changes. The cancer cells that might do best in an environment saturated ...

SAN FRANCISCO, CA--June 23, 2021--A healthy heart is a pliable, ever-moving organ. But under stress--from injury, cardiovascular disease, or aging--the heart thickens and stiffens in a process known as fibrosis, which involves diffuse scar-like tissue. Slowing or stopping fibrosis to treat and prevent heart failure has long been a goal of cardiologists.

Now, researchers at Gladstone Institutes have discovered a master switch for fibrosis in the heart. When the heart is under stress, they found, the gene MEOX1 is turned on in cells called fibroblasts, spurring fibrosis. Their new study, published in the journal Nature, suggests that blocking ...