INFORMATION:

For a complete list of contributors, their affiliations and financial support for this work, go to the publication in eLife.

Glial cells help mitigate neurological damage in Huntington's disease

2021-06-24

(Press-News.org) The brain is not a passive recipient of injury or disease. Research has shown that when neurons die and disrupt the natural flow of information they maintain with other neurons, the brain compensates by redirecting communications through other neuronal networks. This adjustment or rewiring continues until the damage goes beyond compensation.

This process of adjustment, a result of the brain's plasticity, or its ability to change or reorganize neural networks, occurs in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's disease (HD). As the conditions progress, many genes change the way they are normally expressed, turning some genes up and others down. The challenge for researchers like Dr. Juan Botas who studies HD, has been to determine which of the gene expression changes are involved in causing the disease and which ones help mitigate the damage, as this may be critical for designing effective therapeutic interventions.

In his lab at Baylor College of Medicine, Botas and his colleagues look to understand what causes the loss of communication or synapses between neurons in HD. Up until now, research has focused on neurons because the normal huntingtin gene, whose mutation causes the condition, contributes to maintaining healthy neuronal communication. In the current work, the researchers looked into synapses loss in HD from a different perspective.

Focusing on glia to understand Huntington's disease

The mutated huntingtin gene is not only present in neurons, but in all the cells in the body, opening the possibility that other cell types also could be involved in the condition.

"In this study we focused on glia cells, which are a type of brain cell that is just as important as neurons to neuronal communication," said Botas, professor of molecular and human genetics and of molecular and cellular biology at Baylor and a member of the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children's Hospital.

We thought that glia might be playing a role in either contributing or compensating for the damage observed in Huntington's disease."

Initially thought to be little more than housekeeping cells, glia turned out to have more direct roles in promoting normal neuronal and synaptic function.

In a previous work, Botas and his colleagues studied a fruit fly model of HD that expresses the human mutant huntingtin (mHTT) gene in neurons, to understand which of the many gene expression changes that occur in HD are causing disease and which ones are compensatory.

"One class of compensatory changes affected genes involved in synaptic function. Could glia be involved?" Botas said. "To answer this question, we created fruit flies that express mHTT only in glia, only in neurons or in both cell types."

Comparing changes in gene expression

The researchers began their investigation by comparing the changes in gene expression present in the brains of healthy humans with those in human HD subjects and in HD mouse and fruit fly models. They identified many genes whose expression changed in the same direction across all three species but were particularly intrigued when they discovered that having HD reduces the expression of glial cell genes that contribute to maintaining neuronal connections.

"To investigate whether the reduction of expression of these genes in glia either helped with disease progression or with mitigation, we manipulated each gene either in neurons, glial cells or both cell types in the HD fruit fly model. Then we determined the effect of the gene expression change on the function of the flies' nervous system," Botas said.

They evaluated the flies' nervous system health with a high-throughput automated system that assessed locomotor behavior quantitatively. The system filmed the flies as they naturally climbed up a tube. Healthy flies readily climb, but when their ability to move is compromised, the flies have a hard time climbing. The researchers looked at how the flies move because one of the characteristics of HD is progressive disruption of normal body movements.

Turning down the genes worked

The results revealed that in HD, turning down glial genes involved in synaptic assembly and maintenance is protective.

Fruit flies with the mutant huntingtin gene in their glial cells in which the researchers had deliberately turned down synaptic genes climbed up the tube better than flies in which the synaptic genes were not dialed down.

"Our study reveals that glia affected by HD respond by tuning down synapse genes, which has a protective effect," Botas said. "Some gene expression changes in HD promote disease progression, but other changes in gene expression are protective. Our findings suggest that antagonizing all disease-associated alterations, for example using drugs to modify gene expression profiles, may oppose the brain's efforts to protect itself from this devastating disease. We propose that researchers studying neurological disorders could deepen their analyses by including glia in their investigations."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New two-step algorithm could prove "a paradigm shift" in cloud data confidentiality

2021-06-24

The central goal of cloud computing is to provide fast, easy-to-use computing and data storage services at a low cost. However, the cloud environment comes with data confidentiality risks attached.

Cryptography is the primary tool used to enhance the security of cloud computing. This mathematical technique protects the stored or transmitted data by encrypting it, so that it can only be understood by intended recipients. While there are many different encryption techniques, none are completely secure, and the search continues for new technologies that can counter the rising threats to data privacy and security.

In a recent study published in KeAi's International Journal of Intelligent Networks, a team of researchers from India and Yemen describe a novel, two-step cryptography ...

South Korean team to develop nanofilm-based "cell cage" technology

2021-06-24

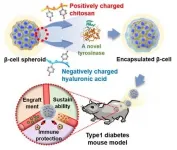

A research team, led by Prof. Nathaniel S. Hwang and Prof. Byung-gee Kim, from Seoul National University (SNU) and Prof. Dong Yun Lee, from Hanyang University, has used enzymatic crosslinking to create nanofilms on cell surfaces. SNU has announced that it has developed a "cell caging" technology for the applications in cell-based therapies. The "cell caging" technique can prevent immune rejection during heterologous islet cell transplantation, facilitate smooth cell insulin secretion, and treat type 1 diabetic patients without immunosuppressants.

The research team succeeded in producing a nanofilm by using the electrostatic force to stack chitosan, which is a biological polymer, and hyaluronic acid in that order. To overcome the shortcomings ...

Enlisting the newly discovered L-IST RNA in the fight against type 2 diabetes

2021-06-24

Across the world, type 2 diabetes is on the rise. A research group has discovered a new gene that may hold the key to preventing and treating lifestyle related diseases such as type 2 diabetes.

The results of their research were published in the journal Nucleic Acids Research on June 18, 2021.

Selenoprotein P (SeP) is an essential plasma protein containing the micronutrient selenium. However, too much SeP spells trouble.

Excess SeP increases insulin resistance, thus weakening the effect of insulin, and worsening the metabolism of glucose.

"Excess SeP is the enemy when it comes to type 2 diabetes," stressed professor Yoshiro Saito from the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Tohoku University and co-author of the ...

Elephant seal diving mystery solved: 24-hour feeding could be climate change sentinel

2021-06-24

Female elephant seal weigh on average 350 kg, and dive continuously to the ocean's mesopelagic zone, about 200 to 1,000 meters deep, to consume their only prey: small fish that weigh less than 10 grams. Now, an international team of researchers, armed with eight years of data, may have answered a decades-long question: How do seals maintain their large size on such small prey?

They published their answer on May 12 in Science Advances.

"It is not easy to get fat," said paper author Taiki Adachi, research fellow with the National Institute of Polar Research and the School of Biology, University of St Andrews. "Elephant seals have to spend almost ...

Genome study reveals East Asian coronavirus epidemic 20,000 years ago

2021-06-24

Genome study reveals East Asian coronavirus epidemic 20,000 years ago

An international study has discovered a coronavirus epidemic broke out in the East Asia region more than 20,000 years ago, with traces of the outbreak evident in the genetic makeup of people from that area.

Professor Kirill Alexandrov from CSIRO-QUT Synthetic Biology Alliance and QUT's Centre for Genomics and Personalised Health, is part of a team of researchers from the University of Arizona, the University of California San Francisco, and the University of Adelaide who have published their findings in the journal Current Biology.

In the past 20 years, there have been three outbreaks of epidemic severe coronaviruses: ...

Multiple dinosaur species not only lived in the Arctic, they also nested there

2021-06-24

In the 1950s, researchers made the first unexpected discoveries of dinosaur remains at frigid polar latitudes. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on June 24 have uncovered the first convincing evidence that several species of dinosaur not only lived in what's now Northern Alaska, but they also nested there.

"These represent the northernmost dinosaurs known to have existed," says Patrick Druckenmiller of the University of Alaska Museum of the North. "We didn't just demonstrate the presence of perinatal remains--in the egg or just hatched--of one or two species, rather we documented at ...

Research team discovers Arctic dinosaur nursery

2021-06-24

Images of dinosaurs as cold-blooded creatures needing tropical temperatures could be a relic of the past.

University of Alaska Fairbanks and Florida State University scientists have found that nearly all types of Arctic dinosaurs, from small bird-like animals to giant tyrannosaurs, reproduced in the region and likely remained there year-round.

Their findings are detailed in a new paper published in the journal Current Biology.

"It wasn't long ago that people were pretty shocked to find out that dinosaurs lived up in the Arctic 70 million years ago," said Pat Druckenmiller, the paper's lead author and director of the ...

Marmoset study identifies brain region linking actions to their outcomes

2021-06-24

The 'anterior cingulate cortex' is key brain region involved in linking behaviours to their outcomes.

When this region was temporarily silenced, monkeys did not change behaviour even when it stopped having the expected outcome.

The finding is a step towards targeted treatment of human disorders involving compulsive behaviour, such as OCD and eating disorders, thought to involve impaired function in this brain region.

Researchers have discovered a specific brain region underlying 'goal-directed behaviour' - that is, when we consciously do something with a particular goal in mind, for example going to the shops to buy food.

The ...

Many cancer patients may need a sequential one-two punch of immunotherapies

2021-06-24

LA JOLLA, CA--New research led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) and the University of Liverpool may explain why many cancer patients do not respond to anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapies--also called checkpoint inhibitors.

The team reports that these patients may have tumors with high numbers of T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells.

In a healthy person, Tfr cells do the important job of stopping haywire T cells and autoantibodies from attacking the body's own tissues. But in a cancer patient, Tfr cells dramatically dial back the body's ability to kill cancer cells.

Anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapies boost the body's cancer-fighting T cells, but ...

Nanotech and AI could hold key to unlocking global food security challenge

2021-06-24

'Precision agriculture' where farmers respond in real time to changes in crop growth using nanotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI) could offer a practical solution to the challenges threatening global food security, a new study reveals.

Climate change, increasing populations, competing demands on land for production of biofuels and declining soil quality mean it is becoming increasingly difficult to feed the world's populations.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that 840 million people will be affected by hunger by 2030, but researchers have developed a roadmap combining smart and nano-enabled agriculture with AI and machine learning capabilities that could help to reduce this ...