Scientists can predict and design single atom catalysts for important chemical reactions

Using fundamental calculations of molecular interactions, they created a catalyst with 100% selectivity in producing propylene, a key precursor to plastics and fabric manufacturing

2021-06-24

(Press-News.org) Researchers at Tufts University, University College London (UCL), Cambridge University and University of California at Santa Barbara have demonstrated that a catalyst can indeed be an agent of change. In a study published today in Science, they used quantum chemical simulations run on supercomputers to predict a new catalyst architecture as well as its interactions with certain chemicals, and demonstrated in practice its ability to produce propylene - currently in short supply - which is critically needed in the manufacture of plastics, fabrics and other chemicals. The improvements have potential for highly efficient, "greener" chemistry with a lower carbon footprint.

The demand for propylene is about 100 million metric tons per year (worth about $200 billion), and there is simply not enough available at this time to meet surging demand. Next to sulfuric acid and ethylene, its production involves the third largest conversion process in the chemical industry by scale. The most common method for producing propylene and ethylene is steam cracking, which has a yield limited to 85% and is one of the most energy intensive processes in the chemical industry. The traditional feedstocks for producing propylene are by-products from oil and gas operations, but the shift to shale gas has limited its production.

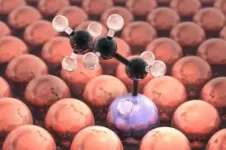

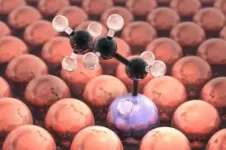

Typical catalysts used in the production of propylene from propane found in shale gas are made up of combinations of metals that can have a random, complex structure at the atomic level. The reactive atoms are usually clustered together in many different ways making it difficult to design new catalysts for reactions, based on fundamental calculations on how the chemicals might interact with the catalytic surface.

By contrast, single-atom alloy catalysts, discovered at Tufts University and first reported in Science in 2012, disperse single reactive metal atoms in a more inert catalyst surface, at a density of about 1 reactive atom to 100 inert atoms. This enables a well-defined interaction between a single catalytic atom and the chemical being processed without being compounded by extraneous interactions with other reactive metals nearby. Reactions catalyzed by single-atom alloys tend to be clean and efficient, and, as demonstrated in the current study, they are now predictable by theorical methods.

"We took a new approach to the problem by using first principles calculations run on supercomputers with our collaborators at University College London and Cambridge University, which enabled us to predict what the best catalyst would be for converting propane into propylene," said Charles Sykes, the John Wade Professor in the Department of Chemistry at Tufts University and corresponding author of the study.

These calculations which led to predictions of reactivity on the catalyst surface were confirmed by atomic-scale imaging and reactions run on model catalysts. The researchers then synthesized single-atom alloy nanoparticle catalysts and tested them under industrially relevant conditions. In this particular application, rhodium (Rh) atoms dispersed on a copper (Cu) surface worked best to dehydrogenate propane to make propylene.

"Improvement of commonly used heterogeneous catalysts has mostly been a trial-and-error process," said Michail Stamatakis, associate professor of chemical engineering at UCL and co-corresponding author of the study. "The single-atom catalysts allow us to calculate from first principles how molecules and atoms interact with each other at the catalytic surface, thereby predicting reaction outcomes. In this case, we predicted rhodium would be very effective at pulling hydrogens off molecules like methane and propane - a prediction that ran counter to common wisdom but nevertheless turned out to be incredibly successful when put into practice. We now have a new method for the rational design of catalysts."

The single atom Rh catalyst was highly efficient, with 100% selective production of the product propylene, compared to 90% for current industrial propylene production catalysts, where selectivity refers to the proportion of reactions at the surface that leads to the desired product. "That level of efficiency could lead to large cost savings and millions of tons of carbon dioxide not being emitted into the atmosphere if it's adopted by industry," said Sykes.

Not only are the single atom alloy catalysts more efficient, but they also tend to run reactions under milder conditions and lower temperatures and thus require less energy to run than conventional catalysts. They can be cheaper to produce, requiring only a small fraction of precious metals like platinum or rhodium, which can be very expensive. For example, the price of rhodium is currently around $22,000 per ounce, while copper, which comprises 99% of the catalyst, costs just 30 cents an ounce. The new rhodium/copper single-atom alloy catalysts are also resistant to coking - a ubiquitous problem in industrial catalytic reactions in which high carbon content intermediates -- basically, soot -- build up on the surface of the catalyst and begin inhibiting the desired reactions. These improvements are a recipe for "greener" chemistry with a lower carbon footprint.

"This work further demonstrates the great potential of single-atom alloy catalysts for addressing inefficiencies in the catalyst industry, which in turn has very large economic and environmental payoffs," said Sykes.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-24

The discovery of a new Homo group in this region, which resembles Pre-Neanderthal populations in Europe, challenges the prevailing hypothesis that Neanderthals originated from Europe, suggesting that at least some of the Neanderthals' ancestors actually came from the Levant.

The new finding suggests that two types of Homo groups lived side by side in the Levant for more than 100,000 years (200-100,000 years ago), sharing knowledge and tool technologies: the Nesher Ramla people who lived in the region from around 400,000 years ago, and the Homo sapiens who arrived later, some 200,000 years ago.

The new discovery also gives clues about a mystery in human evolution: How did genes of Homo sapiens penetrate the Neanderthal population that had presumably lived in Europe long before ...

2021-06-24

Mythological nymphs reincarnate as a group of corn smut proteins to launch a battle on maize immunity. One of these proteins appears to stand out among its sister Pleiades, much like its namesake character in Greek mythology. The research carried out at GMI - Gregor Mendel Institute of Molecular Plant Biology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences - is published in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Pathogenic organisms exist under various forms and use diverse strategies to survive and multiply at the expense of their hosts. Some of these pathogens are termed "biotrophic", as they are parasites that maintain their hosts alive. These biotrophic pathogens deregulate physiological processes in their hosts by suppressing their immune defenses and favoring disease development. ...

2021-06-24

INDIANAPOLIS -- A first-of-its-kind large-scale study of vegetation growth in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 30 years has found that vegetation is becoming increasingly water-limited as global temperatures increase.

The results are significant since vegetation is one of the biggest factors when it comes to controlling water and carbon cycling across Earth, which influences global temperatures. The work by IUPUI and Indiana University Bloomington researchers Wenzhe Jiao, END ...

2021-06-24

(Denver)-Patients with primary lung cancer detected using low-dose computed tomography screening are at reduced risk of developing brain metastases after diagnosis, according to a study published in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

JTO is an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. The full study is available here: Impact of Low-Dose Computed Tomography Screening for Primary Lung Cancer on Subsequent Risk of Brain Metastasis - Journal of Thoracic Oncology (jto.org)

The researchers, led by Summer Han, PhD, from Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo ...

2021-06-24

A new research paper published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition last week showed that a low Omega-3 Index is just as powerful in predicting early death as smoking. This landmark finding is rooted in data pulled and analyzed from the Framingham study, one of the longest running studies in the world.

The Framingham Heart Study provided unique insights into cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors and led to the development of the Framingham Risk Score based on eight baseline standard risk factors--age, sex, smoking, hypertension treatment, diabetes status, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol (TC), and HDL cholesterol.

CVD is still the leading cause of death globally, and risk can be reduced by changing behavioral factors such as unhealthy diet, ...

2021-06-24

A new technique to look at tumors under the microscope has revealed the cellular make-up of Wilm's tumors, a childhood kidney cancer, in unprecedented detail. This new approach could help understand how tumors develop and grow, and fuel research into new treatments for children's cancers.

Scientists at the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology developed a new imaging technique and computational pipeline to study millions of cells in 3D tissue, revealing hundreds of features from each individual cell. Their research was published this month in Nature Biotechnology.

By offering a look at individual cells within an intact organ, the new technique helps scientists analyze the molecular profile of the cells, as well as their ...

2021-06-24

DURHAM, N.C. - The brain's neurons tend to get most of the scientific attention, but a set of cells around them called astrocytes - literally, star-shaped cells - are increasingly being viewed as crucial players in guiding a brain to become properly organized.

Specifically, astrocytes, which form about half the mass of a human brain, seem to guide the formation of synapses, the connections between neurons that are formed and remodeled as we learn and remember.

A new study from Duke and UNC scientists has discovered a crucial protein involved in the communication and coordination between astrocytes as they build synapses. Lacking this molecule, called hepaCAM, astrocytes aren't as sticky as they ...

2021-06-24

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (June 24, 2021) -- The same taste-sensing molecule that helps you enjoy a meal from your favorite restaurant may one day lead to improved ways to treat diabetes and other metabolic and immune diseases.

TRPM5 is a specialized protein that is concentrated in the taste buds, where it helps relay messages to and from cells. It has long been of interest to researchers due to its roles in taste perception and blood sugar regulation.

Now, a team led by scientists at Van Andel Institute has published the first-ever high-resolution images of TRPM5, which reveal two areas that may serve as targets for new medications. The structures also may aid in the development of low-calorie alternative sweeteners that mimic sugar. The findings were published today in Nature ...

2021-06-24

BELLINGHAM, Washington, USA - The open access Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems (JATIS) has published END ...

2021-06-24

The study was conducted by an international collaboration involving the research team led by Luca Tiberi of the Armenise-Harvard Laboratory of Brain Cancer at the Department of Cellular, computational and integrative biology - Cibio of UniTrento, the Paris Brain Institute-Institut du Cerveau at Sorbonne Université in Paris, the Hopp Children´s Cancer Center (KiTZ) in Heidelberg, Germany, and Sapienza University in Rome. It was supported by Fondazione Armenise-Harvard, Fondazione Airc (Italian Association for Cancer Research) and Fondazione Caritro from Trento. The findings of the study, published in Science Advances, could lead to better and more effective treatments.

The team of researchers is proud of the results achieved. Luca Tiberi, coordinator of the study and corresponding ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists can predict and design single atom catalysts for important chemical reactions

Using fundamental calculations of molecular interactions, they created a catalyst with 100% selectivity in producing propylene, a key precursor to plastics and fabric manufacturing