(Press-News.org) When most Americans think of seaweed, they probably conjure images of a slimy plant they encounter at the beach. But seaweed can be a nutritious food too. A pair of UConn researchers recently discovered Connecticut-grown sugar kelp may help prevent weight gain and the onset of conditions associated with obesity.

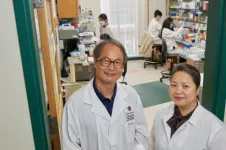

In a paper published in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry by College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources faculty Young-Ki Park, assistant research professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, and Ji-Young Lee, professor and head of the Department of Nutritional Sciences, the researchers reported significant findings supporting the nutritional benefits of Connecticut-grown sugar kelp. They found brown sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) inhibits hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a mouse model of diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, a fatty liver disease.

They studied the differences between three groups of mouse models. They placed two on high-fat diets but incorporated sugar kelp, a kind of seaweed, into the diet of one. The third group was on a low-fat diet as a healthy control. The group that ate sugar kelp had lower body weight and less adipose tissue inflammation - a key factor in a host of obesity-related diseases - than the other high-fat group.

Consuming sugar kelp also helped prevent the development of steatosis, the accumulation of fat in the liver. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a condition often associated with obesity that can cause inflammation and reduced functionality in the liver.

The mice on the sugar kelp diet also had healthier gut microbiomes. The microbiome is a collection of bacteria and other microorganisms in and on our bodies. The diversity and composition of the microbiome are key to maintaining a host of health functions.

"I wasn't surprised to see the data, as we know seaweeds are healthy," Lee says. "But it's still pretty amazing data as this is the first scientific evidence for health benefits of the Connecticut-grown sugar kelp."

This study is the first time researchers have looked at the link between the US-grown sugar kelp and obesity.

"There hadn't been a study about this kind of aspect before," Park says.

Park and Lee saw an opportunity to conduct research on the nutritional science of seaweed, a growing agricultural industry in the United States. They hoped that, by gathering concrete data on the health benefits of sugar kelp, it could encourage people to consume seaweed.

"Consumers these days are getting smarter and smarter," Lee says. "The nutritional aspect is really important for the growth of the seaweed industry in Connecticut."

The researchers specifically used Connecticut-grown sugar kelp, as Connecticut regulates the safety of seaweeds. This is important for monitoring heavy metals that seaweed may absorb from the water.

Most of the seaweed consumed in the US is imported. Park and Lee hope more research on the benefits of locally grown seaweed will prompt consumers to support the industry stateside.

"It's really an ever-growing industry in the world," Lee says.

After completing this pre-clinical study, the researchers now hope to move into clinical studies to investigate the benefits sugar kelp may have for other health concerns. They also want to work on reaching out to people to teach them how to incorporate sugar kelp into their diet.

This work represents a fruitful collaboration between researchers, farmers, and the state.

"Farmers need to know what we're doing is a good thing to help boost their sales," Park says. "We can be a partner."

In collaboration with Anoushka Concepcion, an extension educator with the Connecticut Sea Grant and UConn Extension Program, Park and Lee hope to build stronger partnerships with seaweed growers in Connecticut.

INFORMATION:

FRANKFURT. Cancer and many other diseases are based on genetic defects. The body can often compensate for the defect of one gene; it is only the combination of several genetic errors that leads to the clinical picture. The 3Cs multiplex technique based on CRISPR-Cas technology developed at Goethe University Frankfurt now offers a way to simulate millions of such combinations of genetic defects and study their effects in cell culture. These "gene scissors" make it possible to introduce, remove and switch off genes in a targeted manner. For this purpose, small snippets of genetic material ("single ...

New research from the University of California, Santa Cruz shows how regional shelter-in-place orders during the coronavirus pandemic emboldened local pumas to use habitats they would normally avoid out of fear of humans. This study, published in the journal END ...

Roads, bridges, pipelines and other types of infrastructure in Alaska and elsewhere in the Arctic will deteriorate faster than expected due to a failure by planners to account for the structures' impact on adjacent permafrost, according to research by a University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute permafrost expert and others.

The researchers say planners must account for the sideward repercussions of their projects in addition to the usual projection of the direct top-down effects.

The finding was presented in a May 31 paper in The Cryosphere, a publication of the European Geosciences Union.

UAF Geophysical Institute geophysics professor Vladimir Romanovsky is among the 13 authors ...

For the past several years, chemical engineer Michelle O'Malley has focused her research on the anaerobic fungi found in the guts of herbivores, which make it possible for those animals to fuel themselves with sugars and starches extracted from fibrous plants. O'Malley's work, reflected in multiple research awards and journal articles, has centered on how these powerful fungi might be used to extract value-added products from the nonedible parts of plants -- roots, stems and leaves -- that are generally considered waste products.

Now, her lab has discovered that those same fungi likely produce novel "natural products," which could function as antibiotics or other compounds of use for biotechnology. The research is described in a paper titled "Anaerobic gut ...

The body's immune cells naturally fight off viral and bacterial microbes and other invaders, but they can also be reprogrammed or "trained" to respond even more aggressively and potently to such threats, report UCLA scientists who have discovered the fundamental rule underlying this process in a particular class of cells.

In END ...

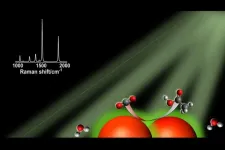

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Researchers report that small quantities of useful molecules such as hydrocarbons are produced when carbon dioxide and water react in the presence of light and a silver nanoparticle catalyst. Their validation study - made possible through the use of a high-resolution analytical technique - could pave the way for CO2-reduction technologies that allow industrial-scale production of renewable carbon-based fuels.

The study, led by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign chemistry professor Prashant Jain, probes chemical activity at the surface of silver nanoparticle catalysts under visible light and uses carbon isotopes to track the origin and production of these previously undetected chemical reactions. The findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.

Sunlight-driven ...

By Benjamin Boettner

(Boston) - Muscular dystrophies are a group of genetic diseases that lead to the progressive loss of muscle mass and function in patients, with the incurable Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), which affects all the body's muscles primarily in boys, being particularly severe. DMD can be caused by more than 7,000 unique mutations in the largest gene of the human genome, which encodes a central protein in muscle fibers. While this astounding number of mutations all variably block muscle function, the affected muscles share another common feature - chronic inflammation.

As chronic inflammation ...

Scientists need to focus on tangible efforts to boost equity, diversity and inclusion in citizen science, researchers from North Carolina State University argued in a new perspective.

Published in the journal Science, the perspective is a response to a debate about rebranding "citizen science," the movement to use crowdsourced data collection, analysis or design in research. Researchers said that while the motivation for rebranding is in response to a real concern, there will be a cost to it, and efforts to make projects more inclusive should go deeper than that. Their recommendations speak to a broader discussion about how to ensure science is responsive to the needs of a diverse audience.

"At its heart, citizen science is a system of knowledge production ...

Parents of children with the most complex medical conditions are more likely to report poor or fair mental health and struggle to find community help, according to a study completed by researchers at University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) and Golisano Children's Hospital. The study was published in Pediatrics, the journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

The study, "A National Mental Health Profile of Parents of Children with Medical Complexity," examined parent-reported data from the National Survey of Children's Health, and compared three groups: households of children with medical complexity (CMC), households of noncomplex children with special health care needs, and households of children ...

Not all stresses are created equal, according to a pair of new studies, which shows that distinct ubiquitination patterns underlie cell recovery following different environmental stressors. Eukaryotic cells respond to environmental stressors - such as temperature extremes, exposure to toxins or damage, for example - through adaptive programs that help to ensure their survival, including the shutdown of key cellular processes. These responses are often associated with the formation of stress granules (SGs) - dense cytoplasmic aggregations of proteins and RNA - as well as with ...