(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. - As mosquito-borne diseases pose risks for half the world's population, scientists have been releasing sterile or genetically modified male mosquitos in attempts to suppress populations or alter their traits to control human disease.

But these technologies have failed to spread very rapidly because they require successful mating of modified mosquitoes with mosquitoes in nature and not enough research exists to fully explain which male traits females seek when they choose a mate.

Now, a new Cornell study of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes investigates how a mating cue called "harmonic convergence" might affect immunity against parasites, bacteria and dengue virus in offspring, which has important implications for trade-offs male mosquitoes make between investing energy towards immunity or investing it on traits that impact mating and fitness.

Previous research has shown that when choosing a mate, a female will use a male's ability to beat his wings at the same frequency as her own as a cue for a male's fitness and desirability. Other studies have also shown that the male offspring from pairs that harmonically converge are better able to achieve harmonic convergence themselves.

"We decided to look to see if the cues that a female responds to might correlate with the downstream genes that a male passes on to offspring that could protect them against parasites and pathogens," said Courtney Murdock, associate professor in the Department of Entomology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and senior author of the paper, "Sex, age, and parental harmonic convergence behavior affect the immune performance of Aedes aegypti offspring," published June 11 in Nature Communications Biology.

Christine Reitmeyer, a former postdoctoral researcher in Murdock's lab who is currently working at the Pirbright Institute in the United Kingdom, is the paper's first author.

In their study, the researchers separated harmonically converging pairs and non-converging pairs of Aedes aegypti, which transmit dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya and Zika viruses. Males and females of each group were housed together for up to four days. Though females avoid mating with non-converging males in the wild, the males will harass the female into mating under these conditions.

The researchers examined a subset of male and female offspring from the convergent pairs and the non-convergent pairs. They then investigated the effects of pairings that resulted from harmonic convergence on three types of offspring immunity, as well as how these effects were altered by offspring sex, age and life-history stage.

They tested humoral melanization, a defense response where insects will coat a pathogen or parasite with melanin in its gut in order to wall it off and prevent infection. They did this by injecting a tiny bead into the mosquitoes' midsection, and then removing the bead and assessing whether the bead was uncoated, partially coated or fully coated.

They also injected mosquitoes with fluorescently labelled Escherichia coli bacteria and tested how well they grew after 24 hours. And they exposed the females (as males don't feed on blood) to dengue virus and looked for its presence in tissues, especially saliva glands, from where the virus is transmitted during a blood meal.

Overall, males were less capable of melanizing beads and resisting bacterial infections than females.

Additionally, male offspring from converging parents were significantly less able to melanize compared with nonconverging male offspring.

"I think this is because males from converging pairs tend to invest more energy in mating effort and the ability to harmonically converge than on immunity, at least when it comes to melanization," Murdock said.

At the same time, these males fended off bacterial infection better than their nonconverging peers at rates similar to females when they were young, but their defenses dropped rapidly as they aged.

With regard to dengue, females from converging parents showed higher immunity early in life, which waned and matched offspring from nonconverging parents as they aged. But overall, the presence of virus found in saliva was so low that the researchers concluded more study is needed.

"The bottom line is that if convergence is going to have an effect, it's going to affect male ability when it comes to immune response," Murdock said, "and then, the direction of the effect is probably going to be dependent upon the physiological costs associated with that immune response."

The findings also have implications for mosquito control, Murdock said. If modified males have introduced traits that make them undesirable to female mosquitoes in nature, these approaches to suppress or replace mosquito populations will not be sustainable in the field over time, she added.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors included Lauren Cator, a lecturer at Imperial College in the U.K., and Laura Harrington, professor of entomology at Cornell.

HOUSTON - (June 24, 2021) - Hold on there, graphene. Seriously, your grip could help make better catalysts.

Rice University engineers have assembled what they say may transform chemical catalysis by greatly increasing the number of transition-metal single atoms that can be placed into a carbon carrier.

The technique uses graphene quantum dots (GQD), 3-5-nanometer particles of the super-strong 2D carbon material, as anchoring supports. These facilitate high-density transition-metal single atoms with enough space between the atoms to avoid clumping.

An international team led by chemical and biomolecular engineer Haotian Wang of Rice's Brown School of ...

Optical superoscillation refers to a wave packet that can oscillate locally in a frequency exceeding its highest Fourier component. This intriguing phenomenon enables production of extremely localized waves that can break the optical diffraction barrier. Indeed, superoscillation has proven to be an effective technique for overcoming the diffraction barrier in optical superresolution imaging. The trouble is that strong side lobes accompany the main lobes of superoscillatory waves, which limits the field of view and hinders application.

There also are tradeoffs between the main lobes and the side lobes of superoscillatory wave packets: reducing the superoscillatory feature size of the ...

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists identified how SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, gets inside cells to cause infection. All current COVID-19 vaccines and antibody-based therapeutics were designed to disrupt this route into cells, which requires a receptor called ACE2.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that a single mutation gives SARS-CoV-2 the ability to enter cells through another route - one that does not require ACE2. The ability to use an alternative entry pathway opens up the possibility of evading COVID-19 antibodies or vaccines, but the researchers did not find evidence of such evasion. However, the discovery does show that the ...

DUARTE, Calif. -- City of Hope, a world-renowned cancer research and treatment center, has identified how cancer cells in patients with early-stage breast cancer change and become resistant to hormone or combination therapies, according to a END ...

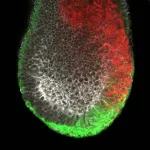

Scientists from Helmholtz Zentrum München revise the current textbook knowledge about gastrulation, the formation of the basic body plan during embryonic development. Their study in mice has implications for cell replacement strategies and cancer research.

Gastrulation is the formation of the three principal germ layers - endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. Understanding the formation of the basic body plan is not only important to reveal how the fertilized egg gives rise to an adult organism, but also how congenital diseases arise. In addition, gastrulation serves as the basis to understand processes during embryonic development called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition which is known to lead to cancer metastasis in adulthood ...

When most Americans think of seaweed, they probably conjure images of a slimy plant they encounter at the beach. But seaweed can be a nutritious food too. A pair of UConn researchers recently discovered Connecticut-grown sugar kelp may help prevent weight gain and the onset of conditions associated with obesity.

In a paper published in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry by College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources faculty Young-Ki Park, assistant research professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, and Ji-Young Lee, professor and head of the Department of Nutritional Sciences, the researchers reported significant findings supporting the nutritional benefits of Connecticut-grown sugar kelp. They found brown sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) ...

FRANKFURT. Cancer and many other diseases are based on genetic defects. The body can often compensate for the defect of one gene; it is only the combination of several genetic errors that leads to the clinical picture. The 3Cs multiplex technique based on CRISPR-Cas technology developed at Goethe University Frankfurt now offers a way to simulate millions of such combinations of genetic defects and study their effects in cell culture. These "gene scissors" make it possible to introduce, remove and switch off genes in a targeted manner. For this purpose, small snippets of genetic material ("single ...

New research from the University of California, Santa Cruz shows how regional shelter-in-place orders during the coronavirus pandemic emboldened local pumas to use habitats they would normally avoid out of fear of humans. This study, published in the journal END ...

Roads, bridges, pipelines and other types of infrastructure in Alaska and elsewhere in the Arctic will deteriorate faster than expected due to a failure by planners to account for the structures' impact on adjacent permafrost, according to research by a University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute permafrost expert and others.

The researchers say planners must account for the sideward repercussions of their projects in addition to the usual projection of the direct top-down effects.

The finding was presented in a May 31 paper in The Cryosphere, a publication of the European Geosciences Union.

UAF Geophysical Institute geophysics professor Vladimir Romanovsky is among the 13 authors ...

For the past several years, chemical engineer Michelle O'Malley has focused her research on the anaerobic fungi found in the guts of herbivores, which make it possible for those animals to fuel themselves with sugars and starches extracted from fibrous plants. O'Malley's work, reflected in multiple research awards and journal articles, has centered on how these powerful fungi might be used to extract value-added products from the nonedible parts of plants -- roots, stems and leaves -- that are generally considered waste products.

Now, her lab has discovered that those same fungi likely produce novel "natural products," which could function as antibiotics or other compounds of use for biotechnology. The research is described in a paper titled "Anaerobic gut ...