Scientists use NASA satellite data to track ocean microplastics from space

2021-06-25

(Press-News.org) Scientists from the University of Michigan have developed an innovative way to use NASA satellite data to track the movement of tiny pieces of plastic in the ocean.

Microplastics form when plastic trash in the ocean breaks down from the sun's rays and the motion of ocean waves. These small flecks of plastic are harmful to marine organisms and ecosystems. Microplastics can be carried hundreds or thousands of miles away from the source by ocean currents, making it difficult to track and remove them. Currently, the main source of information about the location of microplastics comes from fisher boat trawlers that use nets to catch plankton - and, unintentionally, microplastics.

The new technique relies on data from NASA's Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System (CYGNSS), a constellation of eight small satellites that measures wind speeds above Earth's oceans and provides information about the strength of hurricanes. CYGNSS also uses radar to measure ocean roughness, which is affected by several factors including wind speed and debris floating in the water.

Working backward, the team looked for places where the ocean was smoother than expected given the wind speed, which they thought could indicate the presence of microplastics. Then they compared those areas to observations and model predictions of where microplastics congregate in the ocean. The scientists found that microplastics tended to be present in smoother waters, demonstrating that CYGNSS data can be used as a tool to track ocean microplastic from space.

INFORMATION:

The results were published online on June 9, 2021 in IEEE Transactions of Geoscience and Remote Sensing. The work was done by Chris Ruf, professor at the University of Michigan and principal investigator for CYGNSS, and undergraduate student Madeline C. Evans.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-25

New Rochelle, NY, June 24, 2021—The American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the European Thyroid Association, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging released a joint statement on three key topics addressing controversies in thyroid cancer care. The joint statement is published in the peer-reviewed journal Thyroid®, the official journal of the American Thyroid Association® (ATA®).Click here to read the statement now.

An inter-societal working group addressed the current controversies and evolving concepts in three main areas: peri-operative risk stratification; the role of diagnostic radioactive iodine ...

2021-06-25

Toronto, ON - Despite research showing associations between anabolic steroid use and criminal offending, the possibility of a similar association between legal performance-enhancing substance use, such as creatine, and criminal offending remained unknown. A new study published online in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence now shows that both forms of performance-enhancing substance use is longitudinally associated with criminal offending among U.S. adults.

The study, which analyzed a sample of over 9,000 U.S. participants from the National Longitudinal Study ...

2021-06-25

Liza Makowski, PhD, professor in the Department of Medicine and the UTHSC Center for Cancer Research, has long been interested in how the immune system is altered by obesity and how this impacts cancer risk and treatment.

"Obesity is complex, because it can cause both inflammation and activate counter-inflammation pathways leading to immunosuppression," Dr. Makowski said. "How obesity impacts cancer treatments is understudied."

Obese patients with breast cancer often have worse outcomes than non-obese patients. However, exciting developments are being made in other cancers that may also hold promise for treating breast cancer. In studies of ...

2021-06-25

"Fit for 55": under this heading, the EU Commission will specify the implementation of the European Green Deal on 14 July. This refers to the more ambitious climate policy announced, with 55 instead of 40 percent emission reduction by 2030 (relative to 1990), and net-zero emissions in 2050. Coordination between the 27 EU states is expected to be difficult since unanimity is usually required here for sweeping changes. An economic model study by the Berlin-based climate research institute MCC (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change) and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) examines how to achieve good results under such conditions. The study has just been published in the renowned Journal of Environmental ...

2021-06-25

New SARS-CoV-2 variants are spreading rapidly, and there are fears that current COVID-19 vaccines won't protect against them. The latest in a series of structural studies of the SARS-CoV-2 variants' "spike" protein, led by Bing Chen, PhD, at Boston Children's Hospital, reveals new properties of the Alpha (formerly U.K.) and Beta (formerly South Africa) variants. Of note, it suggests that current vaccines may be less effective against the Beta variant.

Spike proteins, on the surface of SARS CoV-2, are what enable the virus to attach to and enter our cells, and all current vaccines are directed against them. The new study, published in Science on June 24, used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) ...

2021-06-25

LA JOLLA, CA--Researchers at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) have shed light on a process in immune cells that may explain why some people develop cardiovascular diseases.

Their research, published recently in Genome Biology, shows the key role that TET enzymes play in keeping immune cells on a healthy track as they mature. The scientists found that other enzymes do play a role in this process--but TET enzymes do the heavy lifting.

"If we can figure out what's going on with these enzymes, that could be important for controlling cardiovascular disease," ...

2021-06-25

Scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology design polymers infused with a stress-sensitive molecular unit that respond to external forces by switching on their fluorescence. The researchers demonstrate the fluorescence to be dependent on the magnitude of force and show that it is possible to detect both, reversible and irreversible polymer deformations, opening the door to the exploration of new force regimes in polymers.

Besides causing physical motion, mechanical forces can drive chemical changes in controlled and productive ways, allowing for desirable material properties. One way to go about this is by introducing a so-called mechanophore ...

2021-06-25

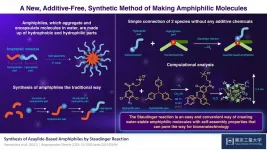

Amphiphilic molecules, which aggregate and encapsulate molecules in water, find use in several fields of chemistry. The simple, additive-free connection of hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules would be an efficient method for amphiphilic molecule synthesis. However, such connections, or bonds, are often fragile in water. Now, scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology have developed an easy way to prepare water-stable amphiphiles by simple mixing. Their new catalyst- and reagent-free method will help create further functional materials.

Soaps and detergents are used to clean things like clothes and dishes. But how do they actually work? It turns out that they are made of long molecules ...

2021-06-25

A study from UCLA neurologists challenges the idea that the brain recruits existing neurons to take over for those that are lost from stroke. It shows that in mice, undamaged neurons do not change their function after a stroke to compensate for damaged ones.

A stroke occurs when the blood supply to a certain part of the brain is interrupted, such as by a blood clot. Brain cells in that area become damaged and can no longer function.

A person who is having a stroke may temporarily lose the ability to speak, walk, or move their arms. Few patients recover fully and most are left with some disability, but the majority exhibit some degree of spontaneous recovery during the first few weeks after the stroke.

Doctors and scientists don't fully ...

2021-06-25

A near-perfectly preserved ancient human fossil known as the Harbin cranium sits in the Geoscience Museum in Hebei GEO University. The largest of known Homo skulls, scientists now say this skull represents a newly discovered human species named Homo longi or "Dragon Man." Their findings, appearing in three papers publishing June 25 in the journal The Innovation, suggest that the Homo longi lineage may be our closest relatives--and has the potential to reshape our understanding of human evolution.

"The Harbin fossil is one of the most complete human cranial fossils in the world," says author Qiang Ji, a professor of paleontology of Hebei GEO University. "This fossil preserved many ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists use NASA satellite data to track ocean microplastics from space