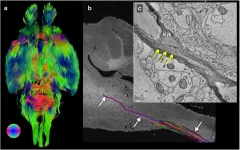

(Press-News.org) Researchers at the University of Chicago and the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory have leveraged existing advanced X-ray microscopy techniques to bridge the gap between MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and electron microscopy imaging, providing a viable pipeline for multiscale whole brain imaging within the same brain. The proof-of-concept demonstration involved imaging an entire mouse brain across five orders of magnitude of resolution, a step which researchers say will better connect existing imaging approaches and uncover new details about the structure of the brain.

The advance, which was published on June 9 in NeuroImage, will allow scientists to connect biomarkers at the microscopic and macroscopic level, improving the resolution of MRI imaging and providing greater context for electron microscopy.

"Our lab is really interested in mapping brains at multiple scales to get an unbiased description of what brains look like," said senior author Narayanan "Bobby" Kasthuri, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurobiology at UChicago and neuroscience researcher at Argonne. "When I joined the faculty here, one of the first things I learned was that Argonne had this extremely powerful X-ray microscope, and it hadn't been used for brain mapping yet, so we decided to try it out."

The microscope uses a type of imaging called synchrotron-based X-ray tomography, which can be likened to a "micro-CT", or micro-computerized tomography scan. Thanks to the powerful X-rays produced by the synchrotron particle accelerator at Argonne, the researchers were able to image the entire mouse brain -- roughly one cubic centimeter -- at the resolution of a micron, 1/10,000 of a centimeter. It took roughly six hours to collect images of the entire brain, adding up to around 2 terabytes (TB) of data. This is one of the fastest approaches for whole brain imaging at this level of resolution.

MRI can quickly image the whole brain to trace neuronal tracts, but the resolution isn't sufficient to observe individual neurons or their connections. On the other end of the scale, electron microscopy (EM) can reveal the details of individual synapses, but generates an enormous amount of data, making it computationally challenging to look at pieces of brain tissue larger than a few micrometers in volume. Existing techniques for studying neuroanatomy at the micrometer resolution typically are either merely two-dimensional or use protocols that are incompatible with MRI or EM imaging, making it impossible to use the same brain tissue for imaging at all scales.

The researchers quickly realized that their new micro-CT, or μCT, approach could help bridge this existing resolution gap. "There have been a lot of imaging studies where people use MRI to look at the whole brain level and then try to validate those results using EM, but there's a discontinuity in the resolutions," said first author Sean Foxley, PhD, Research Assistant Professor at UChicago. "It's hard to say anything about the large volume of tissue you see with an MRI when you're looking at an EM dataset, and the X-ray can bridge that gap. Now we finally have something that can let us look across all levels of resolution seamlessly."

Combining their expertise in MRI and EM, Foxley, Kasthuri, and the rest of their team opted to attempt mapping a single mouse brain using these three approaches. "Why did we choose the mouse brain? Because it fits in the microscope," Kasthuri said with a laugh. "But also, the mouse is the workhorse of neuroscience; they're very useful for analyzing different experimental conditions in the brain."

After collecting and preserving the tissue, the team placed the sample in an MRI scanner to collect structural images of the entire brain. Next, it was placed on a rotating stage in the μCT scanner at the Advanced Photon Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, to collect the CT data before specific regions of interest were identified in the brainstem and cerebellum for targeting for EM.

After months of data processing and image tracing, the researchers determined that they were able to use the structural markers identified on the MRI to localize specific neuronal subgroups in designated brain regions, and that they could trace the size and shape of individual cell bodies. They could also trace the axons of individual neurons as they traveled through the brain, and could connect the information from the μCT images with what they saw at the synaptic level with the EM.

This approach, the team says, will not only be helpful for imaging the brain at the μCT resolution, but also for informing MRI and EM imaging.

"Imaging a 1-millimeter cube of the brain with EM, which is the equivalent to about the minimum resolution of an MRI image, produces almost a million gigabytes of data," Kasthuri said. "And that's just looking at a 1-millimeter cube! I don't know what's happening in the next cube, or the next, so I don't really have context for what I'm seeing with EM. MRI can provide some context except that scale is too big to bridge. Now this μCT gives us that needed context for our EM work."

On the other end of the scale, Foxley is excited about how this approach can be helpful for understanding the living brain through MRI. "This technique gives us a really clear way to identify changes in the microstructure of the brain when there is a disease or injury present," he said. "So now we can start looking for biomarkers with the μCT that we can then trace back to what we see on the MRI in the living brain. The X-ray lets us look at things on the cellular level, so then we can ask, what changed at the cellular level that produced a global change in the MRI signal on a macroscopic level?"

The researchers are already using this technique to begin exploring important questions in neuroscience, looking at the brains of mice that have been genetically engineered to develop Alzheimer's disease to see if they can trace the A? plaques seen with μCT back to measurable changes in MRI scans, especially in early stages of the disease.

Importantly, because this work was done at the national laboratory, this resource will be open and freely accessible to other scientists around the world, making it possible for researchers to begin asking and answering questions that span the whole brain and reach down to the synaptic level.

At the moment, however, the UChicago team is most interested in continuing to refine the technique. "The next step is to do an entire primate brain," said Kasthuri. "The mouse brain is possible, and useful for pathological models. But what I really want to do is get an entire primate brain imaged down to the level of every neuron and every synaptic connection. And once we do that, I want to do an entire human brain."

INFORMATION:

The study, "Multi-modal imaging of a single mouse brain over five orders of magnitude of resolution," was supported by a Technical Innovation Award from the McKnight Foundation, a Brain Initiative grant (U01 MH109100), the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (F31NS113571), and the National Institutes of Health (R01EB026300, S10-OD025081, S10-RR021039, and P30- CA14599). Additional authors include Vandana Sampathkumar, Scott Trinkle, Anastasia Sorokina, Katrina Norwood, and Patrick La Riviere of UChicago and Vincent De Andrade of Argonne National Laboratory.

As social media and other online networking sites have grown in usage, so too has trolling - an internet practice in which users intentionally seek to draw others into pointless and, at times, uncivil conversations.

New research from Brigham Young University recently published in the journal of Social Media and Society sheds light on the motives and personality characteristics of internet trolls.

Through an online survey completed by over 400 Reddit users, the study found that individuals with dark triad personality traits (narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy) combined with schadenfreude - a German word meaning that one derives pleasure from another's misfortune - were more likely to demonstrate trolling behaviors.

"People who exhibit ...

A discovery by a team of researchers, led by a Geisinger professor, could yield a potential new treatment for breast cancer.

In a study published this month in Cell Reports, the team used small molecules known as peptides to disrupt a complex of two proteins, RBM39 and MLL1, that is found in breast cancer cells but not in normal cells.

The research team discovered that the abnormal interaction between RBM39 and MLL1 is required for breast cancer cells to multiply and survive. The team developed non-toxic peptides that prevent these proteins from interacting in breast cancer cells, disrupting their growth and survival.

"Because these proteins do not interact in normal ...

Anxiety, commonly termed as a feeling of fear, dread, and restlessness, is a perfectly normal reaction to stressful situations. However, a state of heightened anxiety, which is the reality for thousands of people who struggle to cope with these feelings, is called anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorder can invoke debilitating fear or apprehension, even without any immediate threat. Though intensive research over the years has yielded a plethora of information, and effective drugs like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been used to alleviate this condition, a lot remains to be understood about this complex condition and ...

The first two COVID-19 vaccines authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) employed a technology that had never before been used in FDA-approved vaccines. Both vaccines performed well in clinical trials, and both have been widely credited with reducing disease, but concerns remain over how long immunity induced by the new vaccine technology will last.

Now, a study from researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, published June 28 in the journal Nature, has found evidence that the immune response to such vaccines is both strong and potentially long-lasting. Nearly four months after the first dose, people who received the Pfizer vaccine still had so-called germinal centers in their lymph nodes churning out ...

The use of transparent masks during communication increases comprehension of speech by about 10% for people with hearing loss and people with normal hearing, according to a study published in the journal Ear and Hearing.

The study was conducted at the University of Texas in Dallas (USA), with the participation of Regina Tangerino, a professor at the University of São Paulo's Bauru Dental School (FOB-USP) in Brazil, and with support from São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP.

"Our findings show that wearing a transparent mask can facilitate communication for everyone, ...

Hotels that opened their doors to homeless people in their community during lockdown generated greater positive word-of-mouth marketing than those that offered free accommodation to frontline healthcare workers, finds new University research.

However, despite the positive impact on tourists' intentions to share the good news story, the immediate impact on intention to book a visit was the reverse, with people less inclined to book a stay at a hotel that had housed homeless people.

Researchers at the Universities of Bath and Southampton were struck by news reports of the 'heart-warming initiatives' to offer free accommodation and wanted to investigate how they compared in terms of business benefit to the tourism sector.

"Our study found that hotels that ...

A global leading cause of death today is a class of dreaded disorders called cardiovascular diseases (CVD), which are ailments of the heart and blood vessels, such as arrhythmia, stroke, coronary artery diseases, cardiac arrest, and so on. The causes for each CVD are different and can be genetic or lifestyle related; but one key risk factor is hypertension, also known as high blood pressure (BP). For instance, as a recent paper published in Chinese Medical Journal notes, in 2017, hypertension was a factor in over 2.5 million deaths in China alone, 95.7% of which were due to CVD.

In this paper, Dr. Jing Liu, expert in the epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases ...

Scientists at the University of Southampton have found that a marine invasive species - a sea squirt that lives on rocky shores - could spread along 3,500 kilometres of South American coastline if climate change or human activities alter sea conditions.

The researchers - working with colleagues at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile; Flinders University, Australia; University of Johannesburg and Rhodes University, South Africa - analysed the creature's DNA and used predictive modelling to identify regions it could move to and thrive in.1 Findings are published in the journal PNAS.

The team took a multidisciplinary approach to predict the potential distribution of a species that is currently restricted. Studying species with small distributions ...

A new approach to molecular drug design has yielded a highly promising bladder cancer drug, which induced rapid shedding of tumour cells and resulted in a significant reduction in tumour size when used in clinical trials.

These potent effects were seen in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and the treatment was shown to be safe, as no drug-related side effects were observed.

The exciting research involved a collaborative group of scientists from Trinity College Dublin, Charles University and Motol Hospital (Prague), Lund University, and startup company Hamlet Pharma. The study has just been published in leading journal Nature Communications.

Bladder cancer - a global killer

Bladder cancer is the fifth most common malignancy in Europe (and the ...

Preliminary results from the European gene therapy trial for Crigler-Najjar syndrome, conducted by Genethon in collaboration with European network CureCN, were presented at the EASL (European Association for the Study of the Liver) annual International Liver Congress on June 26. Based on initial observations, the drug candidate is well tolerated and the first therapeutic effects have been demonstrated, to be confirmed as the trial continues.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a rare genetic liver disease characterized by abnormally high levels of bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinemia). This accumulation of bilirubin is caused by a deficiency of the UGT1A1 enzyme, responsible for transforming bilirubin into a substance that can be eliminated by the ...