(Press-News.org) Scientists isolated a molecule, extracted from the leaves of the European chestnut tree, with the power to neutralize dangerous, drug-resistant staph bacteria. Frontiers in Pharmacology published the finding, led by scientists at Emory University.

The researchers dubbed the molecule Castaneroxy A, after the genus of the European chestnut, Castanea. The use of chestnut leaves in traditional folk remedies in rural Italy inspired the research.

"We were able to isolate this molecule, new to science, that occurs only in very tiny quantities in the chestnut leaves," says Cassandra Quave, senior author of the paper and associate professor in Emory's Center for the Study of Human Health and the School of Medicine's Department of Dermatology. "We also showed how it disarms Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by knocking out the bacteria's ability to produce toxins."

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) causes infections that are difficult to treat due to its resistance to antibiotics. It is one of the most serious infectious disease concerns worldwide, labeled as a "serious threat" by the Centers for the Disease Control and Prevention. In the United States alone, nearly 3 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the U.S. each year, killing more than 35,000 people.

Antibiotics work by killing staph bacteria, which can lead to greater resistance among those few bacteria that survive, spawning "super bugs." The Quave lab has identified compounds from the Brazilian peppertree, in addition to the European chestnut tree, that simply neutralize the harmful effects of MRSA, allowing cells and tissue to naturally heal from an infection without boosting resistance.

"We're trying to fill the pipeline for antimicrobial drug discovery with compounds that work differently from traditional antibiotics," Quave says. "We urgently need these new strategies." She notes that antimicrobial infections kill an estimated 700,000 globally each year, and that number is expected to grow exponentially if new methods of treatment are not found.

First author of the Frontiers in Pharmacology paper is Akram Salam, who did the research as a PhD student in the Quave lab through Emory's Molecular Systems and Pharmacology Graduate Program.

Quave is a medical ethnobotanist, researching traditional plant remedies to find promising leads for new drugs. Although many major drugs are plant-based, from aspirin (the bark of the willow tree) to Taxol (the bark of the Pacific yew tree), Quave is one of the few ethnobotanists with a focus on antibiotic resistance.

The story behind the current paper began more than a decade ago, when Quave and her colleagues researched written reports and conducted hundreds of field interviews among people in rural southern Italy. That pointed them to the European, or sweet, chestnut tree, native to Southern Europe and Asia Minor. "In Italian traditional medicine, a compress of the boiled leaves is applied to the skin to treat burns, rashes and infected wounds," Quave says.

Quave took specimens back to her lab for analysis. By 2015, her lab published the finding that an extract from the leaves disarms even the hyper-virulent MRSA strains capable of causing serious infections in healthy athletes. Experiments also showed the extract did not disturb normal, healthy bacteria on skin cells.

Finally, the researchers demonstrated how the extract works, by inhibiting the ability of MRSA bacteria to communicate with one another, a process known as quorum sensing. MRSA uses this sensing signaling system to make toxins and ramp up its virulence.

For the current paper, the researchers wanted to isolate these active ingredients from the plant extract. The process is painstaking when done manually, because plant extracts typically contain hundreds of different chemicals. Each chemical must be separated out and then tested for efficacy. Large scale fraction collectors, coupled to high-performance liquid chromatographic systems, automate this separation process, but they can cost tens of thousands of dollars and did not have all the features the Quave lab needed.

Marco Caputo, a research specialist in the lab, solved the problem. Using a software device from a child's toy, the LEGO MINDSTORMS robot creator, a few LEGO bricks, and some components from a hardware store, Caputo built an automated liquid separator customized to the lab's needs for $500. The lab members dubbed the invention the LEGO MINDSTORMS Fraction Collector. They published instructions for how to build it in a journal so that other researchers can tap the simple, but effective, technology.

The Quave lab first separated out a group of molecules from the plant extract, cycloartane triterpenoids, and showed for the first time that this group actively blocks the virulence of MRSA. The researchers then dove deeper, separating out the single, most active molecule from this group, now known as Castaneroxy A.

"Our homemade piece of equipment really helped accelerate the pace of our discovery," Quave says. "We were able to isolate this molecule and derive pure crystals of it, even though it only makes up a mere .0019 percent of the chestnut leaves."

Tests on mouse skin infected with MRSA, conducted in the lab of co-author Alexander Horswill at the University of Colorado, confirmed the molecule's efficacy at shutting down MRSA's virulence, enabling the skin to heal more rapidly.

Co-author John Bacsa, director of Emory Department of Chemistry's X-ray Crystallography Center, characterized the crystal shape of Castaneroxy A. Understanding the three-dimensional configuration of the crystal is important for future studies to refine and optimize the molecule as a potential therapeutic.

"We're laying the groundwork for new strategies to fight bacterial infections at the clinical level," Quave says. "Instead of being overly concerned about treating the pathogen, we're focusing on ways to better treat the patient. Our goal is not to kill the microbes but to find ways to weaken them so that the immune system or antibiotics are better able to clear out an infection."

INFORMATION:

Emory co-authors of the paper also include graduate students Caitlin Risener and Lewis Marquez; post-doctoral fellow Gina Porras; and former staff scientist James Lyles. Additional authors from the University of Colorado are Young-Saeng Cho and Morgan Brown.

The work was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, Emory's Department of Dermatology, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

COLUMBUS, Ohio -- Mountaintop glacier ice in the tropics of all four hemispheres covers significantly less area -- in one case as much as 93% less -- than it did just 50 years ago, a new study has found.

The study, published online recently in the journal Global and Planetary Change, found that a glacier near Puncak Jaya, in Papua New Guinea, lost about 93% of its ice over a 38-year period from 1980 to 2018. Between 1986 and 2017 the area covered by glaciers on top of Kilimanjaro in Africa decreased by nearly 71%.

The study is the first to combine NASA satellite imagery with data from ice cores drilled during field expeditions on tropical ...

Cunjiang Yu, Bill D. Cook Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Houston, is reporting the development of a camera with a curvy, adaptable imaging sensor that could improve image quality in endoscopes, night-vision goggles, artificial compound eyes and fish-eye cameras.

"Existing curvy imagers are either flexible but not compatible with tunable focal surfaces, or stretchable but with low pixel density and pixel fill factors," reports Yu in Nature Electronics. "The new imager with kirigami design has a high pixel fill factor, before stretching, of 78% and can retain its optoelectronic performance while being biaxially stretched by 30%."

Modern digital camera systems using conventional rigid, flat imaging sensors require ...

The world's human population is expanding, which means even more agricultural land will be needed to provide food for this growing population. However, choosing which areas to convert is difficult and depends on agricultural and environmental priorities, which can vary widely.

A study led by Princeton University illustrates this challenge by using several different approaches to solve the same puzzle: Given a target amount of food, where should new croplands be put to minimize environmental or biodiversity impacts?

The researchers used the country of Zambia as a case study given that it currently harbors a significant ...

PHILADELPHA--Patients who had their wisdom teeth extracted had improved tasting abilities decades after having the surgery, a new Penn Medicine study published in the journal Chemical Senses found. The findings challenge the notion that removal of wisdom teeth, known as third molars, only has the potential for negative effects on taste, and represent one of the first studies to analyze the long-term effects of extraction on taste.

"Prior studies have only pointed to adverse effects on taste after extraction and it has been generally believed that those effects dissipate over time," said senior author Richard L. Doty, PhD, ...

Annapolis, MD; June 28, 2021--Drones keep getting smaller and smaller, while their potential applications keep getting bigger and bigger. And now unmanned aircraft systems are taking on some of the world's biggest small problems: insect pests.

From crop-munching caterpillars to disease-transmitting mosquitoes, insects that threaten crops, ecosystems, and public health are increasingly being targeted with new pest-management strategies that deploy unmanned aircraft systems (UAS, or drones) for detection and control. And a variety of these applications are featured in a new special collection published this week in ...

A new study has found baby coral reef fishes can outpace all other baby fishes in the ocean.

Lead author Adam Downie is a PhD candidate at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University (Coral CoE at JCU).

Mr Downie said when considering aquatic athletes, young coral reef fishes shine: they are some of the fastest babies, swimming around 15-40 body lengths per second.

As a comparison, herring babies swim up to two body lengths per second, and the fastest human in the water, Olympic gold medalist Michael Phelps, can only swim 1.4 body lengths ...

The year 2020 was a period of economic hardship and significant change in a wide range of sectors for most countries. A team of authors from HSE University has explored how Russia will recover from this crisis and which industries will be affected by the economic recovery. Their study was published in the journal Voprosy ekonomiki.

Last year, the global economy experienced a crisis due to the coronavirus pandemic, with output falling by 3.5% compared to 2019. Russia's decline from the coronavirus measures was more moderate than in many developed countries (industrial ...

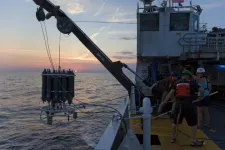

Almost all of the nitrogen that fertilizes life in the open ocean of the Gulf of Mexico is carried into the gulf from shallower coastal areas, researchers from Florida State University found.

The work, published in Nature Communications, is crucial to understanding the food web of that ecosystem, which is a spawning ground for several commercially valuable species of fish, including the Atlantic bluefin tuna, which was a focus of the research.

"The open-ocean Gulf of Mexico is important for a lot of reasons," said Michael Stukel, an associate professor in the Department of Earth, ...

LAWRENCE -- Despite facing cultural and political pushback, the evidence remains clear: Face masks made a difference in Kansas.

"These had a huge effect in counties that had a mask mandate," said Donna Ginther, the Roy A. Roberts Distinguished Professor of Economics and director of the Institute for Policy & Social Research at the University of Kansas. "Our research found that masks reduced cases, hospitalizations and deaths in counties that adopted them by around 60% across the board."

Ginther's article "Association of Mask Mandates and COVID-19 ...

Washington, DC--Location, location, location--when it comes to the placement of wind turbines, the old real estate adage applies, according to new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Carnegie's Enrico Antonini and Ken Caldeira.

Turbines convert the wind's kinetic energy into electrical energy as they turn. However, the very act of installing turbines affects our ability to harness the wind's power. As a turbine engages with the wind, it affects it. One turbine's extraction of energy from the wind influences the ability of its neighbors to do the same.

"Wind is never going to 'run dry' as an energy resource, but our ability to harvest it isn't infinitely scalable either," Antonini explained. "When wind turbines ...