(Press-News.org) URBANA, Ill. - Despite soybean's high protein and oil content and its potential to boost food security on the continent, Africa produces less than 1% of the world's soybean crop. Production lags, in part, because most soybean cultivars are bred for North and South American conditions that don't match African environments.

Researchers from the Soybean Innovation Lab (SIL), a U.S. Agency for International Development-funded project led by the University of Illinois, are working to change that. In a new study, published in Agronomy, they have developed methods to help breeders improve soybean cultivars specifically for African environments, with the intention of creating fast-maturing lines that will bolster harvests and profits for smallholder farmers.

"It is important for producers and breeders to know when a cultivar is going to mature: that moment when a plant is at full capacity and performing its best. We were motivated to fill in gaps of knowledge around maturity timing in Africa," says Guillermo Marcillo, postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Crop Sciences at U of I, and first author on the new study.

Marcillo and his collaborators capitalized on five years of SIL performance trials, encompassing 176 cultivars and experimental lines grown across 68 African sites. The trials are part of SIL's Pan-African Variety Trials (SIL-PAT) network, currently operating across 100 sites and 24 countries.

The researchers analyzed cultivar time-to-maturity against environmental variables, including temperature, day length, and elevation, using a statistical method known as a generalized additive model (GAM). The model was able to predict soybean time-to-maturity within 10 days for cultivars planted across Africa.

"The methodology we implemented is quite innovative, introducing data-driven algorithms and conventional breeding statistics to capture interactions between cultivars and environment in different areas," Marcillo says.

It was important to use a new statistical method to analyze the multi-environment dataset, according to Nicolas Martin, assistant professor in the Department of Crop Sciences and co-author on the study.

"Multi-environment trials allow breeders to analyze crop performance across diverse conditions, but also pose statistical challenges because of unbalanced data. Modern statistical methods, including GAM, can flexibly smooth a range of responses while retaining observations that could be lost under other approaches," he says.

The researchers found environmental factors, specifically daily minimum temperature and change in day length between planting and maturity, were far more important than genotypic differences in predicting time-to-maturity.

"Our study is the first systematic quantification of the effects of these two drivers in Africa," Marcillo says. "We know how temperature and day length affect maturity timing in the U.S., Brazil, and Argentina, but in Africa it's quite a big unknown. If we sent farmers cultivars from these regions, their environments might speed up or slow down maturity quite a bit. This knowledge is a big gain for Africa."

Michelle Da Fonseca Santos, who manages the SIL-PAT trial, notes minimum temperature depends on different factors in Africa compared to soybean-growing regions in North and South America.

"Low temperature is inversely related to elevation. In North and South America, we don't have much variation in elevation, so it's easy for us to divide maturity groups by latitude," she says. "But in Africa, for example in Kenya, if we try to plant the same lines in high elevation locations, they take forever. So we might need to use different lines for different regions depending on elevation."

Time-to-maturity is only one factor breeders need to take into account when developing new cultivars for African environments. Fortunately, the GAM method is flexible.

"We focused on time of maturity in this first project, but our method can apply to many other traits of economic importance such as yield, grain quality, protein content, and oil content," Marcillo says.

The researchers credit SIL-PAT farmers and breeders for making their discoveries possible.

"We couldn't have done anything close to this magnitude without the great work of our SIL-PAT colleagues in assembling the data set. Working with the breeders in each region is almost like a love story. Doing this manually or independently would have been impossible," Martin says.

Da Fonseca Santos adds, "The database is strong because of the public-private partnerships - seed companies, processors, government agencies - we have across Africa. None of this would be possible without them. And it's all demand driven. They all come to us saying we need soybean. So, this work is beneficial on many levels."

INFORMATION:

The article, "Implementation of a generalized additive model (GAM) for soybean maturity prediction in African environments," is published in Agronomy [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11061043]. Authors include Guillermo Marcillo, Nicolas Martin, Brian Diers, Michelle Da Fonseca Santos, Erica Pontes Leles, Josy Francischini, and Godfree Chigeza of the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. Funding was provided by the USAID Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Soybean Value Chain Research (SIL) and partners from private and public sectors in Africa.

The Department of Crop Sciences and SIL are part of the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois.

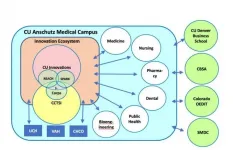

A new study highlights the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus as an example of how an academic medical center can turn groundbreaking research into commercial products that improve patient care and public health.

The paper, published recently in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, focuses on the unique ecosystem at CU Anschutz responsible for these innovations. And it specifically details the campus's collaborative culture and how biomedical research is commercialized.

The campus has successfully turned academic research into a variety of products. CU Anschutz, for example, developed two vaccines for shingles, Zostavax and Shingrix, and ...

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- Biodegradable plastics are supposed to be good for the environment. But because they are specifically made to degrade quickly, they cannot be recycled.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers from the University of Canterbury in New Zealand have developed a method to turn biodegradable plastic knives, spoons, and forks into a foam that can be used as insulation in walls or in flotation devices.

The investigators placed the cutlery, which was previously thought to be "nonfoamable" plastic, into a chamber filled with carbon dioxide. ...

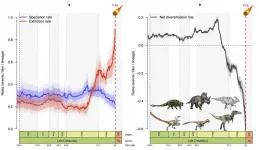

The death of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago was caused by the impact of a huge asteroid on the Earth. However, palaeontologists have continued to debate whether they were already in decline or not before the impact.

In a new study, published today in the journal Nature Communications, an international team of scientists, which includes the University of Bristol, show that they were already in decline for as much as ten million years before the final death blow.

Lead author, Fabien Condamine, a CNRS researcher from the Institut des Sciences de l'Evolution de Montpellier (France), said: "We looked at the six most abundant dinosaur families through the whole of the Cretaceous, spanning from 150 to 66 million ...

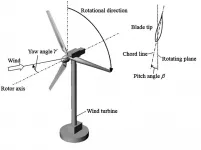

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- As wind passes through a turbine, it creates a wake that decreases the downstream average wind velocity. The faster the spin of the turbine blades relative to the wind speed, the greater the impact on the downstream wake profile.

For wind farms, it is important to control upstream turbines in an efficient manner so downstream turbines are not adversely affected by upstream wake effects. In the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, by AIP Publishing, researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign show by designing controllers based on viewing ...

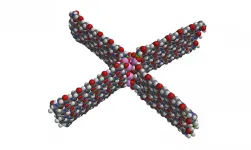

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- Many meteorites, which are small pieces from asteroids, do not experience high temperatures at any point in their existence. Because of this, these meteorites provide a good record of complex chemistry present when or before our solar system was formed 4.57 billion years ago.

For this reason, researchers have examined individual amino acids in meteorites, which come in a rich variety and many of which are not in present-day organisms.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers from Harvard University show the existence of a systematic group of amino acid polymers across several members ...

The oldest strain of Yersinia pestis--the bacteria behind the plague that caused the Black Death, which may have killed as much as half of Europe's population in the 1300s--has been found in the remains of a 5,000-year-old hunter-gatherer. A genetic analysis publishing June 29 in the journal Cell Reports reveals that this ancient strain was likely less contagious and not as deadly as its medieval version.

"What's most astonishing is that we can push back the appearance of Y. pestis 2,000 years farther than previously published studies suggested," says senior author Ben Krause-Kyora, head of the aDNA Laboratory at the University of Kiel in Germany. ...

Ten million years before the well-known asteroid impact that marked the end of the Mesozoic Era, dinosaurs were already in decline. That is the conclusion of the Franco-Anglo-Canadian team led by CNRS researcher Fabien Condamine from the Institute of Evolutionary Science of Montpellier (CNRS / IRD / University of Montpellier), which studied evolutionary trends during the Cretaceous for six major families of dinosaurs, including those of the tyrannosaurs, triceratops, and hadrosaurs. Using a novel statistical modelling method that limited bias associated with gaps in the fossil record, they demonstrated that, for dinosaurs 76 million years ...

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- Computer simulations have been used with great success in recent months to visualize the spread of the COVID-19 virus in a variety of situations. In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers explain how turbulence in the air can create surprising and counterintuitive behavior of exhaled droplets, potentially laden with virus.

Investigators from the University of Florida and Lebanese American University carried out detailed computer simulations to test a mathematical theory they developed previously. They found nearly identical exhalations could spread in different ...

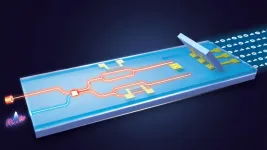

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- As pervasive as they are in everyday uses, like encryption and security, randomly generated digital numbers are seldom truly random.

So far, only bulky, relatively slow quantum random number generators (QRNGs) can achieve levels of randomness on par with the basic laws of quantum physics, but researchers are looking to make these devices faster and more portable.

In Applied Physics Letters, by AIP Publishing, scientists from China present the fastest real-time QRNG to date to make the devices quicker and more portable. The ...

What The Study Did: This study describes four patients who presented with acute myocarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.

Authors: Raymond J. Kim, M.D., of the Duke Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Center in Durham, North Carolina, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2828)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the articles for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflicts of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: ...