These estimates are presented in a study published in Biogeosciences by scientists affiliated with the National Space Research Institute (INPE), the University of São Paulo (USP) and the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in Brazil, and with Munich Technical University (TUM) in Germany.

“CO2 is a basic input for photosynthesis, so when it increases in the atmosphere, plant physiology is affected and this can have a cascade effect on the transfer of moisture from trees to the atmosphere [transpiration], the formation of rain in the region, forest biomass, and several other processes,” said David Montenegro Lapola, last author of the article.

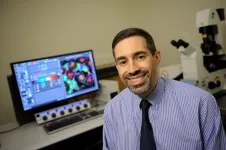

Lapola is a professor at UNICAMP’s Center for Meteorological and Climate Research Applied to Agriculture (CEPAGRI) and principal investigator for a project funded via the FAPESP Research Program on Global Climate Change (RPGCC). The study was also part of a Thematic Project funded by FAPESP and supported by a postdoctoral fellowship awarded to the penultimate author.

The researchers set out to investigate how the physiological effects of rising atmospheric CO2 on plants influence the rainfall regime. Plants transpire less as the supply of CO2 increases, emitting less moisture into the atmosphere and hence generating less rain.

Normally, however, predictions regarding the increase in atmospheric CO2 do not dissociate its physiological effects from its effects on the balance of radiation in the atmosphere. In the latter case, the gas prevents some of the Sun’s reflected energy escaping from the atmosphere, causing the warming phenomenon known as the greenhouse effect.

Projections presented in the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), taking into account changes in the atmospheric radiation balance plus the physiological effects on plants, had already forecast a possible reduction of up to 20% in annual rainfall in the Amazon and shown that much of the change in the region’s precipitation regime will be controlled by the way the forest responds physiologically to the increase in CO2.

For the recently published study, the researchers ran simulations on the supercomputer at INPE’s Center for Weather Forecasting and Climate Studies (CPTEC) in Cachoeira Paulista, state of São Paulo. They projected scenarios in which the atmospheric level of CO2 rose 50% and the forest was entirely replaced by pasture to find out how these changes affected the physiology of the forest over a 100-year period.

“To our surprise, just the physiological effect on the leaves of the forest would generate an annual fall of 12% in the amount of rain [252 millimeters less per year], whereas total deforestation would lead to a fall of 9% [183 mm]. These numbers are far higher than the natural variation in precipitation between one year and the next, which is 5%,” Lapola said.

The findings draw attention to the need for local action to reduce deforestation in the nine countries that share the Amazon basin and global action to reduce CO2 emissions into the atmosphere by factories, vehicles and power plants, for example.

Lapola is one of the coordinators of the AmazonFACE experiment. The acronym stands for Free-Air Carbon dioxide Enrichment. Installed not far north of Manaus, the experiment will raise the level of CO2 over small tracts of rainforest and analyze the resulting changes to plant physiology and the atmosphere. The experiment could anticipate the climate change scenario predicted for this century (more at: agencia.fapesp.br/32470).

Transpiration in forest and pasture

The scenarios projected by the computer simulations showed the decrease in rainfall being caused by a reduction of about 20% in leaf transpiration. The reasons for the reduction are different in each situation, however.

Stomata are microscopic portals in plant leaves that control gas exchange for photosynthesis. They open to capture CO2 and at the same time emit water vapor. In the scenario with more CO2 in the air, stomata remain open for less time and emit less water vapor, reducing cloud formation and rainfall.

Total leaf area shrinkage is another reason. If the entire forest were replaced by pasture, leaf area would shrink 66%. This is because the forest contains several layers of superimposed leaves in trees, so that leaf area per square meter is up to six times what it is on the ground. Lastly, both rising levels of CO2 and deforestation also influence the wind and the movement of air masses, which play a key role in the precipitation regime.

“The forest canopy has a complex surface made up of the tops of tall trees, low trees, leaves and branches. This is called canopy surface roughness. The wind produces turbulence, with eddies and vortices that in turn produce the instability that gives rise to the convection responsible for heavy equatorial rainfall,” Lapola said. “Pasture has a smooth surface over which the wind always flows forward, and without forest doesn’t produce vortices. The wind intensifies as a result, bearing away most of the precipitation westward, while much of eastern and central Amazonia, the Brazilian part, has less rain.”

The decrease in transpiration caused by rising levels of CO2 leads to a temperature increase of up to two degrees because there are fewer water droplets to mitigate the heat. This factor triggers a cascade of phenomena that result in less rain owing to inhibition of so-called deep convection (very tall rain clouds heavy with water vapor).

“A next step would be to test other computational models and compare the results with our findings,” Lapola said. “Another important initiative would consist of more experiments like FACE, as only these can supply data to verify and refine modeling simulations like the ones we performed.”

INFORMATION:

About São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) is a public institution with the mission of supporting scientific research in all fields of knowledge by awarding scholarships, fellowships and grants to investigators linked with higher education and research institutions in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. FAPESP is aware that the very best research can only be done by working with the best researchers internationally. Therefore, it has established partnerships with funding agencies, higher education, private companies, and research organizations in other countries known for the quality of their research and has been encouraging scientists funded by its grants to further develop their international collaboration. You can learn more about FAPESP at http://www.fapesp.br/en and visit FAPESP news agency at http://www.agencia.fapesp.br/en to keep updated with the latest scientific breakthroughs FAPESP helps achieve through its many programs, awards and research centers. You may also subscribe to FAPESP news agency at http://agencia.fapesp.br/subscribe.