(Press-News.org) Our universe is expanding, but our two main ways to measure how fast this expansion is happening have resulted in different answers. For the past decade, astrophysicists have been gradually dividing into two camps: one that believes that the difference is significant, and another that thinks it could be due to errors in measurement.

If it turns out that errors are causing the mismatch, that would confirm our basic model of how the universe works. The other possibility presents a thread that, when pulled, would suggest some fundamental missing new physics is needed to stitch it back together. For several years, each new piece of evidence from telescopes has seesawed the argument back and forth, giving rise to what has been called the 'Hubble tension.'

Wendy Freedman, a renowned astronomer and the John and Marion Sullivan University Professor in Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Chicago, made some of the original measurements of the expansion rate of the universe that resulted in a higher value of the Hubble constant. But in a new review paper accepted to the Astrophysical Journal, Freedman gives an overview of the most recent observations. Her conclusion: the latest observations are beginning to close the gap.

That is, there may not be a conflict after all, and our standard model of the universe does not need to be significantly modified.

The rate at which the universe is expanding is called the Hubble constant, named for UChicago alum Edwin Hubble, SB 1910, PhD 1917, who is credited with discovering the expansion of the universe in 1929. Scientists want to pin down this rate precisely, because the Hubble constant is tied to the age of the universe and how it evolved over time.

A substantial wrinkle emerged in the past decade when results from the two main measurement methods began to diverge. But scientists are still debating the significance of the mismatch.

One way to measure the Hubble constant is by looking at very faint light left over from the Big Bang, called the cosmic microwave background. This has been done both in space and on the ground with facilities like the UChicago-led South Pole Telescope. Scientists can feed these observations into their 'standard model' of the early universe and run it forward in time to predict what the Hubble constant should be today; they get an answer of 67.4 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The other method is to look at stars and galaxies in the nearby universe, and measure their distances and how fast they are moving away from us. Freedman has been a leading expert on this method for many decades; in 2001, her team made one of the landmark measurements using the Hubble Space Telescope to image stars called Cepheids. The value they found was 72. Freedman has continued to measure Cepheids in the years since, reviewing more telescope data each time; however, in 2019, she and her colleagues published an answer based on an entirely different method using stars called red giants. The idea was to cross-check the Cepheids with an independent method.

Red giants are very large and luminous stars that always reach the same peak brightness before rapidly fading. If scientists can accurately measure the actual, or intrinsic, peak brightness of the red giants, they can then measure the distances to their host galaxies, an essential but difficult part of the equation. The key question is how accurate those measurements are.

The first version of this calculation in 2019 used a single, very nearby galaxy to calibrate the red giant stars' luminosities. Over the past two years, Freedman and her collaborators have run the numbers for several different galaxies and star populations. "There are now four independent ways of calibrating the red giant luminosities, and they agree to within 1% of each other," said Freedman. "That indicates to us this is a really good way of measuring the distance."

"I really wanted to look carefully at both the Cepheids and red giants. I know their strengths and weaknesses well," said Freedman. "I have come to the conclusion that that we do not require fundamental new physics to explain the differences in the local and distant expansion rates. The new red giant data show that they are consistent."

University of Chicago graduate student Taylor Hoyt, who has been making measurements of the red giant stars in the anchor galaxies, added, "We keep measuring and testing the red giant branch stars in different ways, and they keep exceeding our expectations."

The value of the Hubble constant Freedman's team gets from the red giants is 69.8 km/s/Mpc--virtually the same as the value derived from the cosmic microwave background experiment. "No new physics is required," said Freedman.

The calculations using Cepheid stars still give higher numbers, but according to Freedman's analysis, the difference may not be troubling. "The Cepheid stars have always been a little noisier and a little more complicated to fully understand; they are young stars in the active star-forming regions of galaxies, and that means there's potential for things like dust or contamination from other stars to throw off your measurements," she explained.

To her mind, the conflict can be resolved with better data.

Next year, when the James Webb Space Telescope is expected to launch, scientists will begin to collect those new observations. Freedman and collaborators have already been awarded time on the telescope for a major program to make more measurements of both Cepheid and red giant stars. "The Webb will give us higher sensitivity and resolution, and the data will get better really, really soon," she said.

But in the meantime, she wanted to take a careful look at the existing data, and what she found was that much of it actually agrees.

"That's the way science proceeds," Freedman said. "You kick the tires to see if something deflates, and so far, no flat tires."

Some scientists who have been rooting for a fundamental mismatch might be disappointed. But for Freedman, either answer is exciting.

"There is still some room for new physics, but even if there isn't, it would show that the standard model we have is basically correct, which is also a profound conclusion to come to," she said. "That's the interesting thing about science: We don't know the answers in advance. We're learning as we go. It is a really exciting time to be in the field."

INFORMATION:

Citation: "Measurements of the Hubble Constant: Tensions in Perspective." Wendy Freedman, The Astrophysical Journal.

Oncotarget published "High in vitro and in vivo synergistic activity between mTORC1 and PLK1 inhibition in adenocarcinoma NSCLC" which reported that the aim of this study was therefore to define combination of treatment based on the determination of predictive markers of resistance to the mTORC1 inhibitor RAD001/Everolimus.

When looking at biomarkers of resistance by RT-PCR study, three genes were found to be highly expressed in resistant tumors, i.e., PLK1, CXCR4, and AXL.

The authors have then focused this study on the combination of RAD001 Volasertib, a PLK1 inhibitor, and observed a high antitumor activity ...

For decades, researchers have been working toward mitigating excess atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. One promising approach captures atmospheric CO2 and then, through CO2 electrolysis, converts it into value-added chemicals and intermediates--like ethanol, ethylene, and other useful chemicals. While significant research has been devoted to improving the rate and selectivity of CO2 electrolysis, reducing the energy consumption of this high-power process has been underexplored.

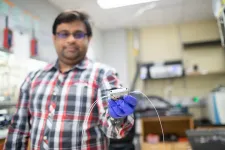

In ACS Energy Letters, researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign report a new opportunity to use magnetism to reduce the energy required for CO2 electrolysis by up to 60% in a flow electrolyzer.

In a ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - Fire can put a tropical songbird's sex life on ice.

Following habitat-destroying wildfires in Australia, researchers found that many male red-backed fairywrens failed to molt into their red-and-black ornamental plumage, making them less attractive to potential mates. They also had lowered circulating testosterone, which has been associated with their showy feathers.

For the study published in the Journal of Avian Biology, the researchers also measured the birds' fat stores and the stress hormone corticosterone but found those remained at normal levels.

"Really, it ended up all coming down to testosterone," said ...

Male jackdaws don't stick around to console their mate after a traumatic experience, new research shows.

Jackdaws usually mate for life and, when breeding, females stay at the nest with eggs while males gather food.

Rival males sometimes visit the nest and attack the lone female, attempting to mate by force.

In the new study, University of Exeter researchers expected males to console their partner after these incidents by staying close and engaging in social behaviours like preening their partner's feathers.

However, males focussed on their own safety - they still brought food to the nest, but they visited less often and spent less time with the female.

"Humans often console friends or family in distress, but it's unclear whether animals do this in the wild," said Beki ...

A new analysis of 58 studies and 44305 patients published in Anaesthesia (a journal of the Association of Anaesthetists) shows that, contrary to some previous research, being male and increasing body mass index (BMI) are not associated with increased mortality in COVID-19 in patients admitted into intensive care (ICU).

However, the study, by Dr Bruce Biccard (Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa) and colleagues finds that a wide range of factors are associated with death from COVID-19 in ICU.

Patients with COVID-19 in ICU were 40% more likely to die with a history of smoking, 54% more likely with high blood pressure, 41% more likely with diabetes, ...

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, a scientific breakthrough that transformed Type 1 diabetes, once known as juvenile diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes, from a terminal disease into a manageable condition.

Today, Type 2 diabetes is 24 times more prevalent than Type 1. The rise in rates of obesity and incidence of Type 2 diabetes are related and require new approaches, according to University of Arizona researchers, who believe the liver may hold the key to innovative new treatments.

"All current therapeutics for ...

Los Angeles, Calif. - The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), the largest global HIV research network, today announced that findings from a sub-study of REPRIEVE (A5332/A5332s, an international clinical trial studying heart disease prevention in people living with HIV) have been published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open (JAMA Network Open). The study found that approximately half of study participants, who were considered by traditional measures to be at low-to-moderate risk of future heart disease, had atherosclerotic plaque in their coronary arteries.

While it is well-known that people living with HIV are at ...

(OTTAWA, ON) The University of Ottawa, the University of Montreal and the Assembly of First Nations are pleased to announce the newly published First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES) in the Canadian Journal of Public Health. Mandated by First Nations leadership across Canada through Assembly of First Nations Resolution 30 / 2007 and realized through a unique collaboration with researchers and communities, the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study is the first national study of its kind. It was led by principal investigators Dr. Laurie Chan, a professor ...

UCLA engineers have demonstrated successful integration of a novel semiconductor material into high-power computer chips to reduce heat on processors and improve their performance. The advance greatly increases energy efficiency in computers and enables heat removal beyond the best thermal-management devices currently available.

The research was led by Yongjie Hu, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. Nature Electronics recently published the finding in this article.

Computer processors have shrunk down to nanometer scales over the years, with billions of transistors sitting on a single computer chip. While the increased number of transistors helps make computers faster and more powerful, it also generates ...

Scientists and doctors at University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (UCL GOS ICH) and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) have given hope of a gene therapy cure to children with a rare degenerative brain disorder called Dopamine Transporter Deficiency Syndrome (DTDS).

The team have recreated and cured the disease using state-of-the-art laboratory and mouse models of the disease and will soon apply for a clinical trial of the therapy. Their breakthrough comes just a decade after the faulty gene causing the disease was first discovered by the lead scientist of this work.

The results, published in Science Translational Medicine, are so promising that the UK regulatory agency MHRA has advised ...