(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- In the late 1800s, scientists were stumped by the "yellow cells" they were observing within the tissues of certain temperate marine animals, including sea anemones, corals and jellyfish. Were these cells part of the animal or separate organisms? If separate, were they parasites or did they confer a benefit to the host?

In a paper published in the journal Nature in 1882, biologist Sir Patrick Geddes of Edinburgh University proffered that not only were these cells distinct entities, but they were also beneficial to the animals in which they lived. He assigned them to a new genus, Philozoon -- from the Greek phileo, meaning 'to love as a friend,' and zoon, meaning 'animal' -- and then promptly changed his career direction to pioneer professions in urban planning and design. Over time, Geddes's scientific contributions were largely forgotten, and the Philozoon genus name was never used.

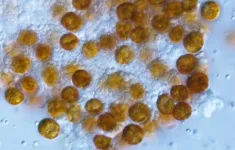

Now, more than a century after Geddes's paper was published, an international team of researchers has revisited these "yellow cells," which, after Geddes, had been determined to be photosynthetic algae in the family Symbiodiniaceae.

In a study published in the June 28 issue of the

European Journal of Phycology, the team resurrected the genus Philozoon by using modern technologies to thoroughly characterize two of the species of algae that Geddes had investigated, along with six new related ones.

"Patrick Geddes was ahead of his time in recognizing the ecological significance of the 'yellow cells' found in some animals were actually distinct entities -- micro-algal symbionts -- existing inside the animal's tissues and creating a photosynthetic animal. That was a major revelation! In fact, we now know that microorganisms live in partnership with all multicellular organisms; for example, the bacteria that comprise our human gut microbiomes are essential for our overall health," said Todd LaJeunesse, professor of biology, Penn State, and lead author of the paper. "By emending and reviving the Philozoon genus, we are honoring the work of this natural historian.

LaJeunesse and his colleagues used genetic information; outward physical, or morphological, characteristics; ecological traits; and geographic distributions to define the diversity found within the newly recognized Philozoon genus. They obtained animal samples -- including from soft and stony corals, jellyfish, and sea anemones -- from locations all over the world. They also obtained samples from Italy where Geddes first conducted his original research.

"Because our team comprises scientists from seven countries, we were able to collect all of these samples, and some during the global pandemic," said LaJeunesse. "This study highlights how the spirit of scientific discovery brings people together, even in times of hardship."

"The fact that these algae exist in animals from the Mediterranean Sea to New Zealand to Chile reminds us how widespread these symbioses are on Earth," said LaJeunesse. "Also, since most of the algae in the family Symbiodiniaceae have been thought to be mostly tropical where they are critical to the formation of coral reefs, finding and describing these new species in cold waters highlights the capacity of these symbioses to evolve and live under a broad range of environmental conditions. Life finds a way to persist and proliferate."

The team documented that at their northernmost and southernmost latitudinal extremes, Philozoon experience water temperatures that may reach winter lows of nearly 40 degrees F and summer highs of close to 90 F.

"The abilities of these Philozoons to withstand a wide range of temperatures is likely due to their diversification during the cooler periods of the late Pliocene and most recent Pleistocene epochs," said LaJeunesse. "This adaptation to a range of temperatures could protect them and the animals with which they associate from some of the effects of climate change, at least in the near term. Similarly, adaptation to high latitude environments may condition Philozoon species to tolerating future increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, which could also help make them resilient to some of the effects of ocean acidification."

He added that careful identification and categorization of these symbiotic algae is essential to understanding the biology and evolution of marine animals that rely on these organisms for their survival.

"The advanced molecular-genetic techniques available to us today have substantially improved our ability to study and understand these microbes," said Pilar Casado-Amezúa, researcher, HyT Association, Spain. "Our new study lays the groundwork for extensive research on the ecological role of animal-algal mutualisms in temperate marine ecosystems."

LaJeunesse noted that although there were a handful of other scientists during the late 1800s that were investigating these 'yellow cells' it was Geddes who unequivocally recognized the full significance of the evidence before him.

He explained, "In describing the associations between the cells and the host animals, Geddes called them 'animal lichens' and eloquently wrote, 'Such an association is far more complex than that of the fungus and alga in the lichen, and indeed stands unique in the physiology as the highest development, not of parasitism, but of the reciprocity between the animal and vegetable kingdoms.' Geddes vigorously contended that these algae were symbiotic in nature. Now, more than a century after their discovery, the true identities of these algae are finally being properly characterized."

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper include Joerg Wiedenmann, University of Southampton, United Kingdom; Pilar Casado-Amezúa, Hombre y Territorio Association, Spain; Isabella D'Ambra, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Italy; Kira Turnham, Penn State, United States; Matthew Nitschke, University of Technology Sydney, Australia, and Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand; Clinton Oakley, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand; Stefano Goffredo, University of Bologna, Spain, and The Inter-Institute Center for Research on Marine Biodiversity, Resources and Biotechnologies, Italy; Carlos Spano, Ecotecnos S.A., Chile; Victor Cubillos, Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile, and Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile; Simon Davy, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand; and David Suggett, University of Technology Sydney, Australia.

Funding for this research was provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the University of Southampton, the Association of Marine Biology Laboratories Program, the ABBaCo project, PO FEAMP Campania and the Australian Research Council.

Giving women in India's Madhya Pradesh state greater digital control over their wages encouraged them to enter the labor force and liberalized their beliefs about working women, concluded a new study co-authored by Yale economists Rohini Pande and Charity Troyer Moore.

The study, published in the American Economic Review, found that a relatively simple intervention directed to poor women -- providing them access to their own bank accounts and direct deposit for their earnings from a federal workfare program, along with basic training on how to use local bank kiosks -- increased the amount ...

Based on fossil finds, we know that the vast majority of species that once inhabited the earth have become extinct. For example, there are about 5,500 mammal species living on the planet today, but we know of at least 160,000 fossil species, so for every mammal species living today, there are at least 30 extinct ones. We therefore know with great certainty that the lineages of living things come and go along immense time scales. But what factors cause these lineages to come into being and disappear is still an unsolved question.

To investigate ...

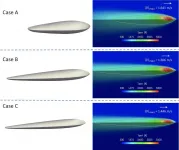

Additive manufacturing has the potential to allow one to create parts or products on demand in manufacturing, automotive engineering, and even in outer space. However, it's a challenge to know in advance how a 3D printed object will perform, now and in the future.

Physical experiments -- especially for metal additive manufacturing (AM) -- are slow and costly. Even modeling these systems computationally is expensive and time-consuming.

"The problem is multi-phase and involves gas, liquids, solids, and phase transitions between them," said University of Illinois Ph.D. student Qiming ...

Early 2020 saw the world break into what has been described as a "war-like situation": a pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the likes of which majority of the living generations across most of the planet have not ever seen. This pandemic has downed economies and resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths. At the dawn of 2021, vaccines have been deployed, but before populations can be sufficiently vaccinated, effective treatments remain the need of the hour.

Thus, other than fast-tracking research into novel drugs, scientists have also been exploring their ...

Breeding better crops through genetic engineering has been possible for decades, but the use of genetically modified plants has been limited by technical challenges and popular controversies. A new approach potentially solves both of those problems by modifying the energy-producing parts of plant cells and then removing the DNA editing tool so it cannot be inherited by future seeds. The technique was recently demonstrated through proof-of-concept experiments published in the journal Nature Plants by geneticists at the University of Tokyo.

"Now we've got a way to modify chloroplast genes specifically and measure their potential to make a good plant," said Associate Professor Shin-ichi ...

"We know that children use a lot of different information sources in their social environment, including their own knowledge, to learn new words. But the picture that emerges from the existing research is that children have a bag of tricks that they can use", says Manuel Bohn, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

For example, if you show a child an object they already know - say a cup - as well as an object they have never seen before, the child will usually think that a word they never heard before belongs with the new object. Why? Children use information ...

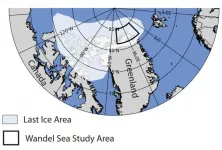

In a rapidly changing Arctic, one area might serve as a refuge - a place that could continue to harbor ice-dependent species when conditions in nearby areas become inhospitable. This region north of Greenland and the islands of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago has been termed the Last Ice Area. But research led by the University of Washington suggests that parts of this area are already showing a decline in summer sea ice.

Last August, sea ice north of Greenland showed its vulnerability to the long-term effects of climate change, according to a study published July 1 in the open-access journal Communications Earth & Environment.

"Current thinking is that this area may be the last refuge for ice-dependent ...

Elephants and their forebears were pushed into wipeout by waves of extreme global environmental change, rather than overhunting by early humans, according to new research.

The study, published today in Nature Ecology & Evolution, challenges claims that early human hunters slaughtered prehistoric elephants, mammoths and mastodonts to extinction over millennia. Instead, its findings indicate the extinction of the last mammoths and mastodonts at the end of the last Ice Age marked the end of progressive climate-driven global decline among elephants over millions of years.

Although elephants today are restricted to just three endangered species in the African and Asian tropics, these are survivors of a once far more diverse and widespread group of giant herbivores, known ...

FINDINGS

Men with high-risk prostate cancer with at least one additional aggressive feature have the best outcomes when treated with multiple healthcare disciplines, known as multimodality care, according to a UCLA study led by Dr. Amar Kishan, assistant professor of radiation oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a researcher at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The study found no difference in prostate cancer-specific deaths across treatment modalities when patients received guideline-concordant multimodality therapy, which in this case was inclusion of hormone therapy for men receiving radiation ...

A water disinfectant created on the spot using just hydrogen and the air around us is millions of times more effective at killing viruses and bacteria than traditional commercial methods, according to scientists from Cardiff University.

Reporting their findings today in the journal Nature Catalysis, the team say the results could revolutionise water disinfection technologies and present an unprecedented opportunity to provide clean water to communities that need it most.

Their new method works by using a catalyst made from gold and palladium that takes in hydrogen and oxygen to form ...