(Press-News.org) Early 2020 saw the world break into what has been described as a "war-like situation": a pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the likes of which majority of the living generations across most of the planet have not ever seen. This pandemic has downed economies and resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths. At the dawn of 2021, vaccines have been deployed, but before populations can be sufficiently vaccinated, effective treatments remain the need of the hour.

Thus, other than fast-tracking research into novel drugs, scientists have also been exploring their arsenals of existing medicines in a bid to find anything that could work against COVID-19. Some approved drugs, like hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, and interferon, have already been put to clinical use against SARS-CoV-2 without well establishing their clinical efficacies, due to the severity of the pandemic. Subsequent randomized trials have not been able to yield a consensus on the efficacy of these drugs. Only remdesivir has been approved for clinical use against severe COVID-19, although its efficacy is still being debated.

In a breakthrough study, a team of scientists--comprising Dr. Koichi Watashi, Kaho Shionoya, Masako Yamasaki, Dr. Hirofumi Ohashi, Dr. Shin Aoki, Dr. Kouji Kuramochi, and Dr. Tomohiro Tanaka from Tokyo University of Science (along with scientists from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Kyushu University, The University of Tokyo, Kyoto University, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, and Science Groove Inc.)--have identified an anti-malarial drug, mefloquine (which is incidentally a derivative of hydrochloroquine), that is effective against SARS-CoV-2. Their findings are published in Frontiers in Microbiology.

Detailing their modus operandi, lead scientist in the team Dr. Watashi says, "To identify drugs with higher antiviral potency than existing antivirals, we first screened approved anti-parasitic/anti-protozoal drugs. We found that mefloquine had the highest anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity among the tested compounds. Upon testing it against other quinoline derivatives, such as hydrochloroquine, in a cell line mimicking the cell-based environments of human lung cells, we found it to be better."

The team further explored mefloquine's mechanism of action. Dr. Watashi explains the process, "In our cell assays, mefloquine readily reduced the viral RNA levels when applied at the viral entry phase but showed no activity during virus-cell attachment. This shows that mefloquine is effective on SARS-COV-2 entry into cells after attachment on cell surface."

Thus, to bolster mefloquine's anti-viral activity, the scientists looked into the possibility of combining it with a drug that inhibits the replication step of SARS-CoV-2: Nelfinavir. Interestingly, they observed that the two drugs acted in "synergy" and the drug combination showed greater anti-viral activity than either showed alone, without being toxic to the cells in the cell lines themselves.

The scientists also mathematically modelled the effectiveness of mefloquine to predict its potential real-world impact if applied to treat COVID-19. What they predicted was that mefloquine could reduce the overall viral load in affected patients to under 7% and shorten the 'time-till-virus-elimination' by 6.1 days.

This study must of course be succeeded by clinical trials, but the world can hope that mefloquine becomes a drug used to effectively treat patients with COVID-19.

INFORMATION:

Reference

Title of original paper: Mefloquine, a Potent Anti-severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Drug as an Entry Inhibitor in vitro

Journal: Frontiers in Microbiology

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.651403

About the Tokyo University of Science

Tokyo University of Science (TUS) is a well-known and respected university, and the largest science-specialized private research university in Japan, with four campuses in central Tokyo and its suburbs and in Hokkaido. Established in 1881, the university has continually contributed to Japan's development in science through inculcating the love for science in researchers, technicians, and educators.

With a mission of "Creating science and technology for the harmonious development of nature, human beings, and society", TUS has undertaken a wide range of research from basic to applied science. TUS has embraced a multidisciplinary approach to research and undertaken intensive study in some of today's most vital fields. TUS is a meritocracy where the best in science is recognized and nurtured. It is the only private university in Japan that has produced a Nobel Prize winner and the only private university in Asia to produce Nobel Prize winners within the natural sciences field.

Website: https://www.tus.ac.jp/en/mediarelations/

About Dr. Koichi Watashi from Tokyo University of Science

Dr. Koichi Watashi is a Visiting Professor at Graduate School of Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science, Japan. Dr. Watashi also works as the Director, Division of Drug Development, Research Center for Drug and Vaccine Development, at National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. He is an expert in virology, with over 20 years of experience in researching molecular mechanisms underlying virus proliferation and corresponding anti-viral agents. He has over 140 publications in international academic journals to his credit. He is the recipient of several prestigious awards like The Young Investigator Award of The Japanese Cancer Association, Sugiura Memorial Incentive Award of The Japanese Society for Virology, etc.

Breeding better crops through genetic engineering has been possible for decades, but the use of genetically modified plants has been limited by technical challenges and popular controversies. A new approach potentially solves both of those problems by modifying the energy-producing parts of plant cells and then removing the DNA editing tool so it cannot be inherited by future seeds. The technique was recently demonstrated through proof-of-concept experiments published in the journal Nature Plants by geneticists at the University of Tokyo.

"Now we've got a way to modify chloroplast genes specifically and measure their potential to make a good plant," said Associate Professor Shin-ichi ...

"We know that children use a lot of different information sources in their social environment, including their own knowledge, to learn new words. But the picture that emerges from the existing research is that children have a bag of tricks that they can use", says Manuel Bohn, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

For example, if you show a child an object they already know - say a cup - as well as an object they have never seen before, the child will usually think that a word they never heard before belongs with the new object. Why? Children use information ...

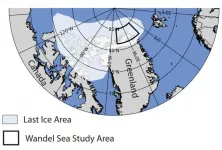

In a rapidly changing Arctic, one area might serve as a refuge - a place that could continue to harbor ice-dependent species when conditions in nearby areas become inhospitable. This region north of Greenland and the islands of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago has been termed the Last Ice Area. But research led by the University of Washington suggests that parts of this area are already showing a decline in summer sea ice.

Last August, sea ice north of Greenland showed its vulnerability to the long-term effects of climate change, according to a study published July 1 in the open-access journal Communications Earth & Environment.

"Current thinking is that this area may be the last refuge for ice-dependent ...

Elephants and their forebears were pushed into wipeout by waves of extreme global environmental change, rather than overhunting by early humans, according to new research.

The study, published today in Nature Ecology & Evolution, challenges claims that early human hunters slaughtered prehistoric elephants, mammoths and mastodonts to extinction over millennia. Instead, its findings indicate the extinction of the last mammoths and mastodonts at the end of the last Ice Age marked the end of progressive climate-driven global decline among elephants over millions of years.

Although elephants today are restricted to just three endangered species in the African and Asian tropics, these are survivors of a once far more diverse and widespread group of giant herbivores, known ...

FINDINGS

Men with high-risk prostate cancer with at least one additional aggressive feature have the best outcomes when treated with multiple healthcare disciplines, known as multimodality care, according to a UCLA study led by Dr. Amar Kishan, assistant professor of radiation oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a researcher at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The study found no difference in prostate cancer-specific deaths across treatment modalities when patients received guideline-concordant multimodality therapy, which in this case was inclusion of hormone therapy for men receiving radiation ...

A water disinfectant created on the spot using just hydrogen and the air around us is millions of times more effective at killing viruses and bacteria than traditional commercial methods, according to scientists from Cardiff University.

Reporting their findings today in the journal Nature Catalysis, the team say the results could revolutionise water disinfection technologies and present an unprecedented opportunity to provide clean water to communities that need it most.

Their new method works by using a catalyst made from gold and palladium that takes in hydrogen and oxygen to form ...

As many expectant mothers know, getting enough folate is key to avoiding neural tube defects in the baby during pregnancy. But for the individuals who carry certain genetic variants, dealing with folate deficiency can be a life-long struggle which can lead to serious neurological and heart problems and even death.

Now a Donnelly Centre study offers clues to how to recognize early those who are most at risk.

Defects in an enzyme called MTHFR, or 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, which modifies folate, or vitamin B9 as it is also known, to produce ...

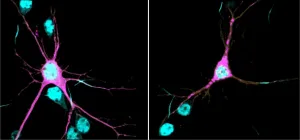

CHAPEL HILL, NC - Scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine and colleagues have demonstrated that variants in the SPTBN1 gene can alter neuronal architecture, dramatically affecting their function and leading to a rare, newly defined neurodevelopmental syndrome in children.

Damaris Lorenzo, PhD, assistant professor in the UNC Department of Cell Biology and member of the UNC Neuroscience Center at the UNC School of Medicine, led this research, which was published today in the journal Nature Genetics. Lorenzo, who is also a member of the UNC Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC) at the UNC School of Medicine, is the ...

Hundreds of genetic drivers affect sexual and reproductive behaviour

Combined with social factors, these can affect longevity and health

An Oxford-led team, working with Cambridge and international scholars, has discovered hundreds of genetic markers driving two of life's most momentous milestones - the age at which people first have sex and become parents.

In a paper published today in Nature Human Behaviour, the team linked 371 specific areas of our DNA, called genetic variants (known locations on chromosomes), 11 of which were sex-specific, to the timing of first sex and birth. These variants interact with environmental factors, such as socioeconomic status and when you were born, and are predictors of longevity and later life disease.

The researchers ...

People who have lost their sense of smell are being failed by healthcare professionals, new research has revealed.

A study by Newcastle University, University of East Anglia and charity Fifth Sense, shows poor levels of understanding and care from GPs and specialists about smell and taste loss in patients.

This is an issue that has particularly come to the forefront during the Covid-19 pandemic as many people who have contracted the virus report a loss of taste and smell as their main symptoms.

Around one in 10 people who experience smell loss as a result of Covid-19 report that their sense of smell has ...