The rise and fall of elephants

2021-07-01

(Press-News.org) Based on fossil finds, we know that the vast majority of species that once inhabited the earth have become extinct. For example, there are about 5,500 mammal species living on the planet today, but we know of at least 160,000 fossil species, so for every mammal species living today, there are at least 30 extinct ones. We therefore know with great certainty that the lineages of living things come and go along immense time scales. But what factors cause these lineages to come into being and disappear is still an unsolved question.

To investigate this problem more closely, the research team focused on a charismatic group: the proboscideans, which include today's elephants, but also the extinct mammoths, mastodons and dinotheria. The history of the proboscideans is one of glory and decline. Although today there are only three species of elephants left in Asia and Africa, we know fossil more than 180 species of these animals, which also inhabited Europe, South America and North America. "In the past, more than 30 species of these giants lived on the planet at the same time, and many ecosystems were so productive and ecologically complex that it was not uncommon for three or more species of proboscideans to live together in the same ecosystem," explains Juan López Cantalapiedra, a researcher at the University of Alcalá in Spain and lead author of the new study.

However, as the researchers were able to show, proboscideans were not always so diverse. In the first 30 million years of their history, the group was limited to Africa and Arabia, which together formed an isolated continent that was not connected to Asia as it is today. Until then, the evolution of these animals was quite slow and the few existing species were ecologically quite similar. But about 22 million years ago, Afro-Arabia connected with Eurasia and the proboscideans spread all over the world. The new challenges faced by the lineages scattered outside Afro-Arabia caused the ecology of the group to multiply. Species emerged with different, highly diverse tooth shapes, including strange, shovel-shaped tusks. "This ecological diversity reduced competition between species and allowed several of them to live together in the same ecosystem at the same time," points out Fernando Blanco, a researcher at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. This marked the beginning of the golden age of proboscideans. "If the link between Afro-Arabia and Eurasia had not happened, or had happened at a different time, the evolutionary history of proboscideans would have been radically different," Blanco adds.

The new study also revealed the factors that determined the group's ultimate decline. Seven million years ago, modern savannah ecosystems spread across all continents, and because of this change, many proboscideans adapted to life in forested areas disappeared. At the same time, however, new forms appeared that were able to feed on less nutritious plant material such as wood and especially grass, which is typical of savannas. Today's elephants are among these evolutionary newcomers.

About 3 million years ago, the rules of the game changed again with the onset of the ice ages. In Eurasia and Africa, the extinction rate quintupled. But as the researchers were able to show, the extinction rate rose even further in Eurasia and America 160,000 and 75,000 years ago, respectively. Were humans responsible for this debacle? "At that time, Homo sapiens had not yet made it to these continents," Cantalapiedra explains. The analyses showed that the different phases of extinction were linked to the decline and rapid fluctuations in global temperatures as a result of the ice ages. "The impact of our ancestors probably contributed to the extinction of the few surviving species, such as the woolly mammoth, a little later."

INFORMATION:

Publication: Cantalapiedra JL, Sanisidro O, Zhang H, Alberdi MT, Prado JL, Blanco F, Saarinen J (2021) The rise and fall of proboscidean ecological diversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01498-w

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-01

Additive manufacturing has the potential to allow one to create parts or products on demand in manufacturing, automotive engineering, and even in outer space. However, it's a challenge to know in advance how a 3D printed object will perform, now and in the future.

Physical experiments -- especially for metal additive manufacturing (AM) -- are slow and costly. Even modeling these systems computationally is expensive and time-consuming.

"The problem is multi-phase and involves gas, liquids, solids, and phase transitions between them," said University of Illinois Ph.D. student Qiming ...

2021-07-01

Early 2020 saw the world break into what has been described as a "war-like situation": a pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the likes of which majority of the living generations across most of the planet have not ever seen. This pandemic has downed economies and resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths. At the dawn of 2021, vaccines have been deployed, but before populations can be sufficiently vaccinated, effective treatments remain the need of the hour.

Thus, other than fast-tracking research into novel drugs, scientists have also been exploring their ...

2021-07-01

Breeding better crops through genetic engineering has been possible for decades, but the use of genetically modified plants has been limited by technical challenges and popular controversies. A new approach potentially solves both of those problems by modifying the energy-producing parts of plant cells and then removing the DNA editing tool so it cannot be inherited by future seeds. The technique was recently demonstrated through proof-of-concept experiments published in the journal Nature Plants by geneticists at the University of Tokyo.

"Now we've got a way to modify chloroplast genes specifically and measure their potential to make a good plant," said Associate Professor Shin-ichi ...

2021-07-01

"We know that children use a lot of different information sources in their social environment, including their own knowledge, to learn new words. But the picture that emerges from the existing research is that children have a bag of tricks that they can use", says Manuel Bohn, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

For example, if you show a child an object they already know - say a cup - as well as an object they have never seen before, the child will usually think that a word they never heard before belongs with the new object. Why? Children use information ...

2021-07-01

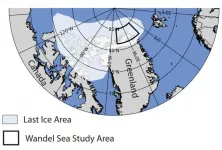

In a rapidly changing Arctic, one area might serve as a refuge - a place that could continue to harbor ice-dependent species when conditions in nearby areas become inhospitable. This region north of Greenland and the islands of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago has been termed the Last Ice Area. But research led by the University of Washington suggests that parts of this area are already showing a decline in summer sea ice.

Last August, sea ice north of Greenland showed its vulnerability to the long-term effects of climate change, according to a study published July 1 in the open-access journal Communications Earth & Environment.

"Current thinking is that this area may be the last refuge for ice-dependent ...

2021-07-01

Elephants and their forebears were pushed into wipeout by waves of extreme global environmental change, rather than overhunting by early humans, according to new research.

The study, published today in Nature Ecology & Evolution, challenges claims that early human hunters slaughtered prehistoric elephants, mammoths and mastodonts to extinction over millennia. Instead, its findings indicate the extinction of the last mammoths and mastodonts at the end of the last Ice Age marked the end of progressive climate-driven global decline among elephants over millions of years.

Although elephants today are restricted to just three endangered species in the African and Asian tropics, these are survivors of a once far more diverse and widespread group of giant herbivores, known ...

2021-07-01

FINDINGS

Men with high-risk prostate cancer with at least one additional aggressive feature have the best outcomes when treated with multiple healthcare disciplines, known as multimodality care, according to a UCLA study led by Dr. Amar Kishan, assistant professor of radiation oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a researcher at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The study found no difference in prostate cancer-specific deaths across treatment modalities when patients received guideline-concordant multimodality therapy, which in this case was inclusion of hormone therapy for men receiving radiation ...

2021-07-01

A water disinfectant created on the spot using just hydrogen and the air around us is millions of times more effective at killing viruses and bacteria than traditional commercial methods, according to scientists from Cardiff University.

Reporting their findings today in the journal Nature Catalysis, the team say the results could revolutionise water disinfection technologies and present an unprecedented opportunity to provide clean water to communities that need it most.

Their new method works by using a catalyst made from gold and palladium that takes in hydrogen and oxygen to form ...

2021-07-01

As many expectant mothers know, getting enough folate is key to avoiding neural tube defects in the baby during pregnancy. But for the individuals who carry certain genetic variants, dealing with folate deficiency can be a life-long struggle which can lead to serious neurological and heart problems and even death.

Now a Donnelly Centre study offers clues to how to recognize early those who are most at risk.

Defects in an enzyme called MTHFR, or 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, which modifies folate, or vitamin B9 as it is also known, to produce ...

2021-07-01

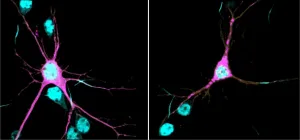

CHAPEL HILL, NC - Scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine and colleagues have demonstrated that variants in the SPTBN1 gene can alter neuronal architecture, dramatically affecting their function and leading to a rare, newly defined neurodevelopmental syndrome in children.

Damaris Lorenzo, PhD, assistant professor in the UNC Department of Cell Biology and member of the UNC Neuroscience Center at the UNC School of Medicine, led this research, which was published today in the journal Nature Genetics. Lorenzo, who is also a member of the UNC Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC) at the UNC School of Medicine, is the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] The rise and fall of elephants