Plastics now are everywhere in our lives, providing low-cost convenience and other benefits in countless applications. They can be shaped to almost any task, from wispy films to squishy children's toys and hard-core components. They have shown themselves vital in medicine and have been pivotal in the global effort to slow the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic over the past 16 months.

Plastics seem indispensable these days.

Unfortunately for the long-term, they are also nearly indestructible. Our planet now bears the weight of more than seven billion tons of plastics, with more being produced every day. An ever-growing waste stream clogs our landfills, pollutes our waterways and poses an urgent crisis for our planet.

Four scientists have published a call to action in a new issue of Science, devoted to the plastics problem.

In a sweeping introductory article, the scientists -- including two from the University of Delaware, one from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California and another from the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom -- call for fundamental change in the way plastics are designed, produced, used and reused.

The ultimate goal: Designing, adopting and ensuring a "circular" lifecycle for plastics that leads not to a landfill or an ocean or a roadside, but to a long life of near-infinite use and reuse of the valuable resources and applications they represent.

That requires new approaches to chemistry, engineering, industrial processes, policy and global collaboration, according to co-authors LaShanda T.J. Korley, director of the Center for Plastics Innovation (CPI) at the University of Delaware and the principal investigator of a National Science Foundation (NSF) Partnerships for International Research and Education effort in Bio-inspired Materials and Systems; UD's Thomas H. Epps, III, co-director of CPI, lead principal investigator of an NSF Growing Convergence Research (GCR) effort in Materials Life-Cycle Management and director of the Center for Hybrid, Active, and Responsive Materials (CHARM) at UD; Brett A. Helms of the Molecular Foundry at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California; and Anthony J. Ryan of the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom.

"The plastics waste dilemma is a global challenge that requires urgent intervention and a concerted effort that links partners across industrial, academic, financial, and government sectors buttressed by significant investments in sustainability," they write.

It's a tall order that includes attention to recycling, "upcycling" (reusing materials in new added-value ways), development of new materials and recognition of the needs of under-resourced communities.

"There's not a one-size-fits-all solution," said Korley, Distinguished Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at UD, who has spent her career developing new plastics with specific properties. "How people live with waste and how they recycle is so different. Traveling in Europe has highlighted the stark contrast in the usage of single-use plastics, such as drinking straws and cutlery in comparison to the U.S. Across the U.S., cities and municipalities within a single state may do things differently."

Complex recipes are used in many plastics, Korley said, and often include several kinds of polymers and other additives. Each component can complicate recycling efforts or make recycling impossible, which is why recyclers will accept some kinds of plastic and refuse others.

But how can plastics be designed so that all of their components can be deconstructed for future use in other products?

This is the challenge for CPI, which Korley directs. Its focus is on "upcycling" plastics -- finding ways to turn plastic waste into valuable materials such as fuels and lubricants. Researchers use catalysis and enzymes to reconstitute some kinds of plastic, such as high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and polystyrene/Styrofoam, the kinds of plastics used in milk jugs, shampoo bottles, sandwich bags, coffee cups, grocery bags and food packaging.

"Different materials properties require the use of different polymers and blends and additives, which contributes to the complexity and hierarchy of waste," Korley said.

The Science paper addresses that and much more, with an urgency that reflects the real and present dangers for a planet choked by discarded plastics that aren't going anywhere anytime soon.

Some of those realities are grim indeed. Take the plastic water bottle that helped quench your thirst after a morning jog five years ago, for example. It will probably be with us -- somewhere -- for another 395 years. Slow deterioration doesn't help us either. Scientists have found that tiny micro bits of worn-down plastic are prevalent in the water we drink and the foods we eat.

Less than 10% of plastic waste is recycled at all and less than 1% will be recycled more than once. About 12% will be incinerated. Millions of tons of discarded plastic winds up in giant swirls of debris in the ocean and the rest of it piles up in landfills, sinks into riverbeds or lies on roadsides around the world.

But Helms, a co-author from the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, was part of the team that created a next-generation plastic called PDK (polydiketoenamine), which can be reduced back to its molecular parts and reassembled as needed.

"We're at a critical point where we need to think about the infrastructure needed to modernize recycling facilities for future waste sorting and processing," Helms said after the new material was announced. "If these facilities were designed to recycle or upcycle PDK and related plastics, then we would be able to more effectively divert plastic from landfills and the oceans. This is an exciting time to start thinking about how to design both materials and recycling facilities to enable circular plastics."

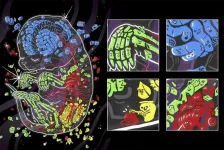

The building blocks of plastics -- monomers -- are made up of elements including carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, chlorine and sulfur. These monomers are linked by chemical bonds to become polymers, which can be used in the formation of plastics to be crafted into various forms for many different uses.

The value of all those resources is lost in single-use applications, said Sheffield's Ryan. He calls it a "convenient truth" -- the convenience and cheap cost of such products make them compelling to consumers, without recognizing the inherent value and cost to the planet. Marketing strategies that claim certain plastic products are "green" and biodegradable to draw well-intentioned consumers are especially concerning to him.

"Cynical 'greenwash' is the biggest problem for plastics sustainability," he said. "So I was very keen to work with LaShanda and Thomas on this. I have known them since they were Ph.D. students."

With innovation and collaboration as pillars of the new centers they co-direct -- Korley's U.S. Department of Energy-backed CPI and Epps' NSF-backed CHARM and GCR, Korley and Epps, the Allan and Myra Ferguson Distinguished Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, are at the forefront of efforts to extend the life of petroleum- and bio-derived plastics and/or put them on a circular path that continues from production to first use to reconstitution to forever.

Ryan said he sees a "circular economy" as critical. He sees the value in recycling and upcycling and development of new materials, but none is a "silver bullet." Addressing the plastics dilemma requires recognition of the true value of plastics.

"One solution is something America is not very good at -- regulations, policy and taxation," he said. "There isn't an easy answer to the plastics problem. An unrestrained market isn't going to provide it.

"For all of these issues where science and engineering and society intersect, the answer is always: It's complicated."

A more accurate perspective, in Ryan's view, is to see the plastics problem as related to the climate change problem without allowing it to be a distraction.

"Climate change is an inconvenient truth and an invisible truth," he said. "You can't see what's causing it and you can't see carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. You don't associate driving to the store with climate change.

"You do associate things with plastics waste -- and that is a convenient truth. We have no problem taking fossil fuels and turning them into plastics. But now we need to take care of that precious plastic. Don't just throw it away. It's just too cheap. Because of the pollution problem, we need to give it an artificially high price."

Lifecycle analysis data are key to making evidence-based decisions, Ryan said, and consumers and lawmakers can't do that on their own. They need professionals to break down the costs and benefits and explain the options.

"It's far more complex than most people are willing to consider," he said.

The call to action is comprehensive.

"To achieve a more sustainable future, integration of not only technological considerations, but also equity analysis, consumer behavior, geographical demands, policy reform, life-cycle assessment, infrastructure alignment, and supply chain partnerships are vital," the authors said.

Korley said she sees growing passion for this daunting challenge.

"These initiatives drive excitement among our students -- high school, undergraduate and graduate and our postdocs," she said. "People are passionate about doing something to better the world. And they can talk to their grandmother or their niece or nephew and explain why the work they are doing matters."

INFORMATION: