Insect-sized robot navigates mazes with the agility of a cheetah

This flexible, durable robot can traverse complex terrain and quickly swerve to avoid obstacles, qualities that could one make it an asset for search and rescue operations

2021-07-02

(Press-News.org) Berkeley -- Many insects and spiders get their uncanny ability to scurry up walls and walk upside down on ceilings with the help of specialized sticky footpads that allow them to adhere to surfaces in places where no human would dare to go.

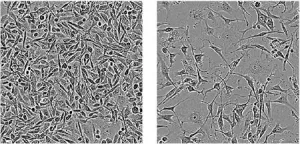

Engineers at the University of California, Berkeley, have used the principle behind some of these footpads, called electrostatic adhesion, to create an insect-scale robot that can swerve and pivot with the agility of a cheetah, giving it the ability to traverse complex terrain and quickly avoid unexpected obstacles.

The robot is constructed from a thin, layered material that bends and contracts when an electric voltage is applied. In a 2019 paper, the research team demonstrated that this simple design can be used to create a cockroach-sized robot that can scurry across a flat surface at a rate of 20 body lengths per second, or about 1.5 miles per hour -- nearly the speed of living cockroaches themselves, and the fastest relative speed of any insect-sized robot.

In a new study, the research team added two electrostatic footpads to the robot. Applying a voltage to either of the footpads increases the electrostatic force between the footpad and a surface, making that footpad stick more firmly to the surface and forcing the rest of the robot to rotate around the foot.

The two footpads give operators full control over the trajectory of the robot, and allow the robot to make turns with a centripetal acceleration that exceeds that of most insects.

"Our original robot could move very, very fast, but we could not really control whether the robot went left or right, and a lot of the time it would move randomly, because if there was a slight difference in the manufacturing process -- if the robot was not symmetrical - it would veer to one side," said Liwei Lin, a professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley. "In this work, the major innovation was adding these footpads that allow it to make very, very fast turns."

To demonstrate the robot's agility, the research team filmed the robot navigating Lego mazes while carrying a small gas sensor and swerving to avoid falling debris. Because of its simple design, the robot can also survive being stepped on by a 120-pound human.

Small, robust robots like these could be ideal for conducting search and rescue operations or investigating other hazardous situations, such as scoping out potential gas leaks, Lin said. While the team demonstrated most of the robot's skills while it was "tethered," or powered and controlled through a small electrical wire, they also created an "untethered" version that can operate on battery power for up to 19 minutes and 31 meters while carrying a gas sensor.

"One of the biggest challenges today is making smaller scale robots that maintain the power and control of bigger robots," Lin said. "With larger-scale robots, you can include a big battery and a control system, no problem. But when you try to shrink everything down to a smaller and smaller scale, the weight of those elements become difficult for the robot to carry and the robot generally moves very slowly. Our robot is very fast, quite strong, and requires very little power, allowing it to carry sensors and electronics while also carrying a battery."

INFORMATION:

Lin is senior author of a paper describing the robot, which appeared online this week in the journal Science Robotics.

Co-authors of the paper include Jiaming Liang, Huimin Chen, Zicong Miao, Hanxiao Liu, Ying Liu, Yixin Liu, Dongkai Wang, Wenying Qiu, Min Zhang and Xiaohao Wang of the Tsinghua University in China; Yichuan Wu of the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China; Justin Yim of Carnegie Mellon University; and Zhichun Shao and Junwen Zhong of UC Berkeley.

This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2020A1515010647), the Shenzhen Fundamental Research Funds (JCYJ20180508151910775), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 52005083) and a Start Research Grant from the University of Macau.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-02

Wander around a desert most anywhere in the world, and eventually you'll notice dark-stained rocks, especially where the sun shines most brightly and water trickles down or dew gathers. In some spots, if you're lucky, you might stumble upon ancient art - petroglyphs - carved into the stain. For years, however, researchers have understood more about the petroglyphs than the mysterious dark stain, called rock varnish, in which they were drawn.

In particular, science has yet to come to a conclusion about where rock varnish, which is unusually rich in manganese, comes from.

Now, scientists at the California Institute of Technology, the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator ...

2021-07-02

Neuroscientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have demonstrated in new research that dopamine plays a key role in how songbirds learn complex new sounds.

Published in the Journal of Neuroscience, the finding that dopamine drives plasticity in the auditory pallium of zebra finches lays new groundwork for advancing the understanding of the functions of this neurotransmitter in an area of the brain that encodes complex stimuli.

"People associate dopamine with reward and pleasure," says lead author Matheus Macedo-Lima, who performed the research in the lab of senior author Luke Remage-Healey as a Ph.D. student in UMass Amherst's Neuroscience and Behavior graduate program. "It's a very well-known concept that dopamine is involved in learning. ...

2021-07-02

In cancer research, it's a common goal to find something about cancer cells -- some sort of molecule -- that drives their ability to survive, and determine if that molecule could be inhibited with a drug, halting tumor growth. Even better: The molecule isn't present in healthy cells, so they remain untouched by the new therapy.

Plenty of progress has been made in this approach, known as molecular targeted cancer therapy. Some current cancer therapeutics inhibit enzymes that become overactive, allowing cells to proliferate, spread and survive beyond ...

2021-07-02

What The Study Did: Researchers in this study aimed to determine how each state and the District of Columbia planned to ensure equitable COVID-19 vaccine distribution.

Authors: Juan C. Rojas, M.D., of the University of Chicago, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15653)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...

2021-07-02

What The Study Did: Changes in the use of women's preventive health services during the COVID-19 pandemic, including screening for sexually transmitted infections, breast and cervical cancer, and obtaining contraceptives from pharmacies are described by researchers in this study.

Authors: Nora V. Becker, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1408)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, ...

2021-07-02

What The Study Did: Researchers estimated the frequency and magnitude of surprise bills for deliveries and newborn hospitalizations, which are the leading reasons for hospitalization in the United States, to illustrate the potential benefits of federal legislation that will protect families from most surprise bills. Potential surprise bills were defined as claims from out-of-network clinicians and ancillary service providers, such as an ambulance.

Authors: Kao-Ping Chua, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1460)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of ...

2021-07-02

What The Study Did: This study investigates whether different risk factors identify the same hospitals caring for a high proportion of disadvantaged patients using seven definitions of social risk.

Authors: Susannah M. Bernheim, M.D., M.H.S., of the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1323)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support ...

2021-07-02

PHILADELPHIA-- While more women are entering the field of academic medicine than ever before, they are less likely to be recognized as experts and leaders; they are less likely to receive prestigious awards, be promoted to full professorships, hold leadership roles, or author original research or commentaries in major journals. What's more, articles published by women in high-impact medical journals also have fewer citations than those written by men, especially when women are primary and senior authors, according to new research from the Perelman School of Medicine and the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, published today in JAMA Open Network.

Researchers found that of the 5,554 articles published in 5 leading academic medical journals ...

2021-07-02

The Mutriku wave power plant was built on the Mutriku breakwater, a site with great wave energy potential, and has been in operation since 2011. With 14 oscillating water columns to transform wave energy, it is the only wave farm in the world that supplies electricity to the grid on a continuous basis. In general, technologies that harness the power of the waves to produce electricity are in their infancy, and this is precisely what is being explored by the UPV/EHU's Research Group EOLO, which focusses on Meteorology, Climate and Environment, among many ...

2021-07-02

CHAPEL HILL, NC - Migraine is one of the largest causes of disability in the world. Existing treatments are often not enough to offer full relief for patients. A new study published in The BMJ demonstrates an additional option patients can use in their effort to experience fewer migraines and headaches - a change in diet.

"Our ancestors ate very different amounts and types of fats compared to our modern diets," said co-first author Daisy Zamora, PhD, assistant professor in the UNC Department of Psychiatry in the UNC School of Medicine. "Polyunsaturated fatty acids, which our bodies do not produce, have increased substantially in our diet due to the addition of oils such as corn, soybean and cottonseed to many processed foods like chips, crackers and granola."

The classes of polyunsaturated ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Insect-sized robot navigates mazes with the agility of a cheetah

This flexible, durable robot can traverse complex terrain and quickly swerve to avoid obstacles, qualities that could one make it an asset for search and rescue operations