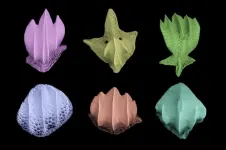

Two types of fin elements Indeed, many fish species possess two types of fin elements, "ordinary" soft fin rays, which are blunt and flexible and primarily serve locomotion, and fin spines, which are sharp and heavily ossified. As fin spines serve the purpose to make the fish less edible, they offer a strong evolutionary advantage. With over 18.000 members, the spiny-rayed fish are the most species-rich fish lineage. These fishes even evolved separate "spiny fins" consisting of spines only. Therefore, the evolution of fin spines is considered a major factor in determining diversity and evolutionary success amongst fishes.

In the study published in PNAS, researchers at the University of Konstanz from a team led by Dr Joost Woltering, who - together with his PhD student and first author of the study Rebekka Höch - works in the laboratory of Professor Axel Meyer, show how fin spines arise during embryonic development. They also explain how the spines could evolve out of ancestral soft-rays independently in different lineages of fish. The study focuses on a model species for the spiny-rayed fish, the cichlid Astatotilapia burtoni, which possesses well-developed soft-rayed and spiny fin parts.

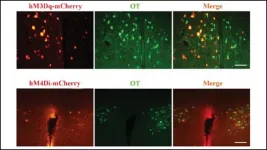

Different developmental genes for spines and soft-rays As a first step, the team determined the genetic profiles of soft-ray and spiny fins during embryonic development. "What became clear from these first experiments was that a set of genes that we already knew from fin and limb development becomes differently activated in spines and soft-rays," says Rebekka Höch. These genes correspond to so-called master regulator genes and are known to determine morphology in the axial and the limb skeleton. In the fish fins, these genes appear to provide a genetic code that determines whether the emerging fin elements will develop looking like a spine or like a soft-ray.

Soft-rays can change into spines and vice versa Next, the team identified genetic pathways that switch on these master regulator genes and that determine their activity at different positions across the fins. "Importantly, we were able to address the roles of these pathways using chemical tools, so-called inhibitors and activators, as well as the 'gene scissors' CRISPR/Cas9 and thereby test how spiny and soft-rayed fin domains are established during development," says Joost Woltering, assistant professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Konstanz and senior author of the study.

In their experiments, the scientists were able to alter the number of spines or soft-rays in the fins. This effect was most striking when the so-called BMP (bone morphogenetic protein) signaling was modulated. "We did not only see changes in the activation of the master regulatory genes, but we also observed so-called homeotic transformations, in which soft-rays had become spines, or the other way around, spines had turned into soft-rays," Joost Woltering explains.

An additional observation was that in these fish not only the morphology of the fin elements changed, but also the accompanying fin coloration. "Male cichlids have bright yellow spots on their fins, but these are restricted to the soft-rayed part. What we observed was that when a soft-ray changed into a spine, the fin also lost the yellow spots at this position," says Joost Woltering. This observation shows that in spiny-rayed fish, spines and soft-rays are integrated parts of a larger developmental module that determines a number of the visible features of the fins.

The same principle in different fish lineages As the puzzle was put together, the team came to realize that a deeply conserved patterning system had become redeployed during evolution of the spiny fin. "In fact, the genetic code that determines the fin domain where spines will appear is also active in fins that do not have spines. This indicates that an ancestral genetic pattern was redeployed for making spines," says Rebekka Höch.

With this newly gained insight in mind the authors set out to investigate fin patterning in catfish, a group of fish of which members have independently evolved spines in the fins. Indeed, the genetic code identified for spines in the cichlid matched the one of the catfish spines. Although some differences exist between the different spiny fish species, it altogether suggests the existence of a deeply conserved fin pattern that is relied on to make spines when this is favored by evolutionary selection.

The next steps For its future research the team will focus on the genes that act downstream of the identified spine and soft-ray control genes to find out how exactly they alter fin morphology by controlling ossification and cellular growth pathways. "In the end we want to gain a better understanding of how new anatomical structures arise that make some species more successful than others, and how this contributed to the incredible evolutionary diversity of the fish lineages," concludes Joost Woltering.

INFORMATION:

Key facts:

THE EMBARGO ON THE PAPER WILL LIFT ON THE 5TH OF JULY (2021) AT 3:00 PM U.S. EASTERN TIME (9:00 PM CEST)!

Original study: Rebekka Höch, Ralf F. Schneider, Alison Kickuth, Axel Meyer, and Joost M. Woltering (2021) Spiny and soft-rayed fin domains in acanthomorph fish are established through a BMP-gremlin-shh signaling network. PNAS; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2101783118

Journalists can access the embargoed article through EurekAlert!

All authors of the study are affiliated with the Department of Biology at the University of Konstanz. Ralf F. Schneider currently works at the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel (Geomar), Alison Kickuth at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG).

Scientific contacts: Dr Joost Woltering (joost.woltering@uni-konstanz.de), Professor Axel Meyer (axel.meyer@uni-konstanz.de)

The BMP (bone morphogenetic protein) and shh (sonic hedgehog) signaling pathways are crucially involved in the formation of the fin pattern of fish during development. They control the activity of master regulatory genes (hoxa13 and alx4) that determine whether the developing fin elements will become soft or spiny fin rays respectively.

A genetic comparison between fishes with spines from different lineages suggests that fin spines have evolved independently several times through repeated redeployment of a highly conserved genetic pattern.

Funding: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; especially #WO-2165/2-1), European Research Council (ERC; #293700) and Young Scholar Fund of the University of Konstanz.

Note to editors:

You can download a photo here:

https://cms.uni-konstanz.de/fileadmin/pi/fileserver/2021/how_fish.jpg

Caption: Two males of the cichlid fish Astatotilapia burtoni, the model organism used to study spine and soft-ray development in Höch et al.

Copyright: Joost Woltering

Contact:

University of Konstanz

Communications and Marketing

Phone: + 49 7531 88-3603

Email: kum@uni-konstanz.de

END